A Placemaking Journal

Housing Policy Repair for a New Era: Let’s review

Since the data keep rolling in, confirming changes we should have anticipated even before the Great Recession, maybe it’s time to revisit the tasks ahead for communities if they’re to avoid flunking the tests of livability and prosperity in the 21st century.

Consider:

Though a narrow sliver of the population seems to have emerged from the recent economic unpleasantness richer than they were going in, the rest of us have to come to terms with the idea we aren’t as smart or wealthy as we thought. What’s more, we sense we aren’t likely to improve our financial situation much without help from the lottery or late life adoption by Russian oligarchs.

Because so many of us are, by necessity, pulling back on spending, our consumer economy is in low gear. Companies are figuring out how to squeeze more profits out of fewer workers and better robots. And governments at every level are slicing away at services and programs that, in other eras, might have provided the most hurting among us some soft places to fall and regroup.

Nowhere are these cascading impacts more apparent than in the housing sector, where the fantasy economy first slammed into reality back in 2007. We’re stuck, on the one hand, with too many drive-til-you-qualify subdivisions that fewer qualify for — or want — and too few choices when it comes to locations and housing types that now seem more practical and appealing.

Lots of folks spotted that widening gap years ago, and we pointed to some of their research in posts like this one, this one and this one. In the last few weeks, we’ve learned more.

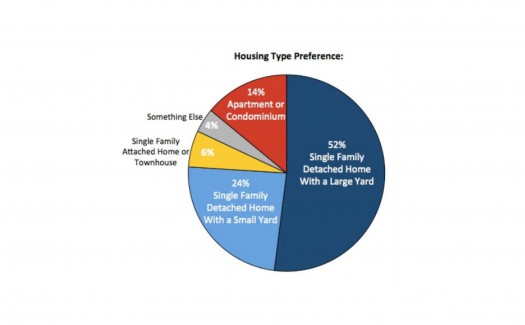

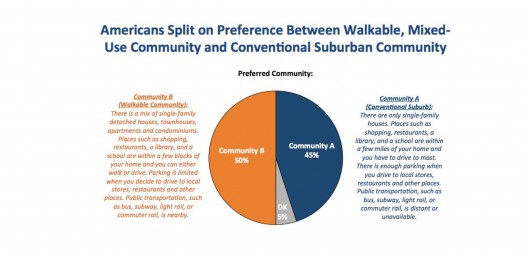

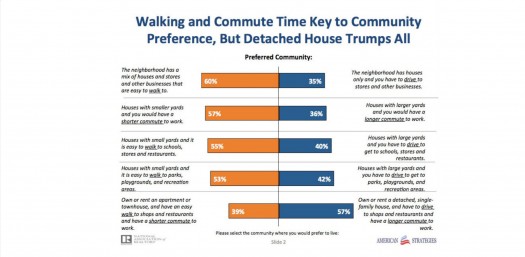

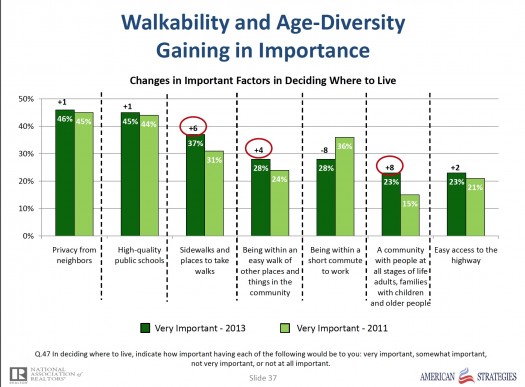

The recently released 2013 National Community Preference Survey from the National Association of Realtors (NAR) updates Americans’ struggle to reconcile privacy, auto dependency and big-yard/big-house dreams with their desire for the convenience, affordability and social amenities associated with smaller scale residences in walkable, mixed-use, transit-served communities. For a downloadable summary of NAR’s survey analysis, go here, where you’ll find PowerPoint-worthy graphics like these (everything’s clickable for a larger view):

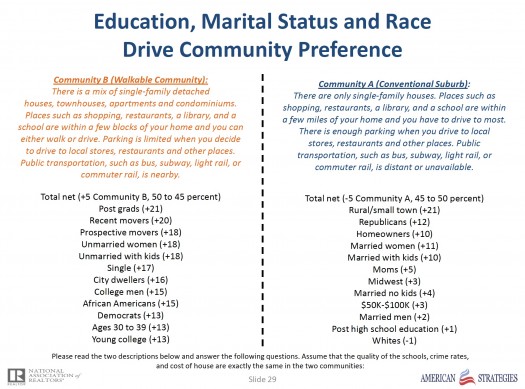

I think it helps to look at the NAR’s breakdown of who’s choosing the walkable, mixed-use option over conventional suburban developments:

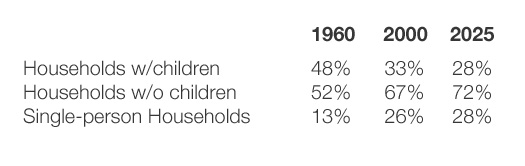

Now consider these demographic projections from the research of Arthur C. Nelson at the University of Utah and co-author of Reshaping Metropolitan America: Development Trends and Opportunities to 2030.

If the people who tend to prefer diverse, walkable, mixed-use housing tend to be younger, educated singles and married folks without children and there’s more of that group every year, you’d expect to see real estate demand increasing in the direction of walkable, mixed-use, no?

And the NAR survey hints that’s the case, when answers to similar questions in 2011 are compared with those in 2013:

Joseph Molinaro, NAR’s director of community outreach programs, sums up the broader implications this way: “Home buyers and renters are consumers of communities as much as they are consumers of housing products.”

That’s the good news from the market demand side, which seems full of opportunity. How ‘bout the supply side?

The supply gap is most obvious in the range of choice for rentals. That’s because the passion to elevate home ownership levels through government policy and private finance was one of the first casualties of the fantasy economy implosion. When lenders stick to the rules for credit worthiness and down payments, families just starting out or those struggling with underwater mortgages on current homes are unlikely qualifiers for financing. And that’s especially true in the most desirable places — like walkable, mixed-use, transit-served communities — where demand is increasing and raising the ante for buyers and renters alike.

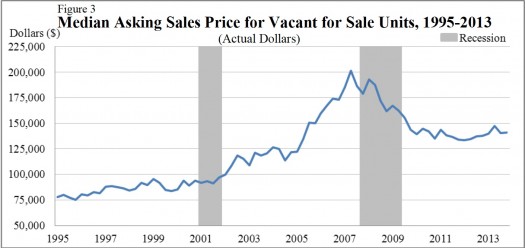

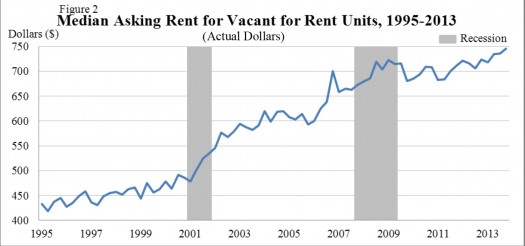

Take a look at the trend directions in these two graphs from a U.S. Census Bureau analysis of asking prices and rents for vacant residential units, 1995-2013:

The increasing demand for rentals is driven by the preferences of people in all age and income groups. Even people who can afford to buy often choose the rental option for flexibility and location. Higher rental prices put the squeeze on all but the most affluent. But for those in the lower income ranks, the affordability challenge has reached crisis levels.

Out of Reach 2014, a study by the National Low Income Housing Coalition, suggests that the hourly wage required for renting a market-rate, two-bedroom apartment has risen to $18.92. “This national average is more than two-and-a-half times the federal minimum wage, and 52% higher than it was in 2000. In no state can a full-time minimum wage worker afford a one-bedroom or a two-bedroom rental unit at Fair Market Rent,” as defined by HUD guidelines.

For those of us who work in communities all across the U.S., I sense an increasing frustration at the persistence of mid-20th-century thinking about housing among local leaders even in the face of a mountain of 21st century evidence that times have changed. City and town planners usually get all this stuff and can be heroic in their advocacy for more market-responsive and fairer ways to guide development and redevelopment. But around a table of community movers and shakers made up of elected officials and the people who most influence them — NIMBYs, conventional real estate development types and others heavily invested in the old ways — planners have little clout.

With so many local governments struggling to find enough money to keep the most basic programs going, much of the funding for figuring out and applying better housing approaches comes from the federal government. With no skin in the game, it’s easier for locals to distance themselves from the policy-making and implementation responsibilities the government grants are intended to encourage. They can outsource accountability to consulting teams and staff and wait to see which way the political winds blow before adopting the results and committing to implementation. A little pushback, a little controversy, a few hard choices, and there goes the plan.

Too bad. Because the changes that are required in the way communities address housing are becoming more obvious every day, and the trauma and expense of adjusting to new ways of doing business will increase proportionately. Which is to say there are going to be lots of losers as well as winners in the new era.

–Ben Brown

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.