A Placemaking Journal

Next Urbanism Lab 02: Planning trends captivate, but…

In not learning from the past we are destined to repeat it. So, in this lab, I’ll examine some of the trends currently dominating planning and begin examining the quirks and pitfalls that can occur when a solution for one city is transplanted somewhere else.

In my last Next Urbanism Lab post, I detailed how my city of San Diego has been built over time through a layering of national planning and development trends — silver bullets, so to speak — in order to chase economic prosperity. Our new convention center, downtown baseball park, mall, and freeway were squished into our traditional urban fabric in order to save our city from some economic malaise at the time.

Well, we are still in the red and still following the latest trends:

1. The Bilbao Effect: Ground zero of Starchitecture. Bilbao’s tourism success convinced every city that they needed to pay an exorbitant amount of money to have Frank Gehry, Zaha Hadid or Rem Koolhaas design an iconic building to draw people from around the world. Our city salivates for a starchitect to build an Opera House on its harbor (sound familiar?).

However, Mr. Gehry’s brilliance was to create a new civic building language that was in stunning contrast and complexity to the traditional private buildings that framed his new museum. In time, however, that context-specificity ceased as Mr. Gehry proceeded to apply the same language everywhere, thus losing the ability to speak between public and private buildings and local citizen values. Bilbao worked great for Bilbao, but the transferable lesson is that places need to understand how to build upon their existing architectural patterns in order to carefully craft new interventions that accentuate or repair their own local architectural language. In short, solutions — even if they emulate success elsewhere — must be crafted in context.

2. The Vancouver Model: A packaged single-point, slender tower sitting atop a multi-story full-block podium base. This model, which focused on the ground floor streetscape, combined the best of suburbia’s buildings (townhouses) with downtown’s buildings (towers) to re-introduce urban housing to San Diego.

However, although the #VAN model may have been a necessary baby step in re-inhabiting our once perceived scary city, the Vancouver model in San Diego ultimately became an obese variation of the great buildings and blocks built to our north because we — like any city — had different rules on the ground. Different rules, different outcomes. Nonetheless, now that we’ve relearned how to live in more urban places, we can move beyond those awkward beginnings and begin to construct more contextually appropriate urban buildings in smaller increments — buildings that connect not only with the streetscape but also with the interior of their blocks and with their surrounding public and private buildings.

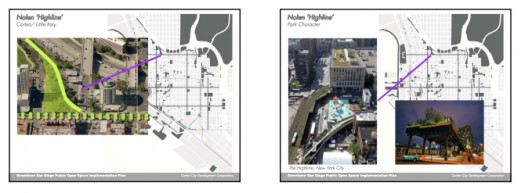

3. The High Line: So violently hip and cool… it hurts. The High Line is the envy of the hipster world and has created a tremendous buzz as a new type of recycled civic space. It’s helped ingrain the new Landscape Urbanism methodology heavily marketed by Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design and has inspired similar projects for San Diego (the John Nolen ‘High Line’ on a freeway overpass) and downtown Chicago’s Bloomingdale Trail/Railway.

However, rather than serving solely as a new, urban, stand-alone civic space type — not unlike plazas, squares, and promenades — the High Line’s real value lies in its lessons for building 3-dimensional civic space that reaches up and connects more vertical cities. What cities need to understand is not how to copy the High Line but, rather, the value of re-purposing and recycling infrastructure to reconnect people, both on upper floors and with streets, squares and plazas on the ground level.

4. Active / Healthy Living Lifestyle: The cities of New York, Boston, San Francisco, and Chicago have taken the initiative to rebrand themselves as healthy places to live. They’ve added bike and car sharing programs, more dedicated bicycle facilities, parklets, bike corrals and other ‘outdoor’ lifestyle infrastructure. In trying to be competitive in the world marketplace, these big city leaders understand that people are eager to live in neighborhoods and places they can inhabit while at work, at home, and at play.

However, ultimately, it’s not about making yours a ‘pedestrian city’ or a ‘bicycle city,’ but about making places within your city that are more conducive to activity in general, allowing the use of all manner of mobility — feet, bikes and cars — to get both to and through them. This is the foundation of any great place, which is increasingly the impetus for people to spend time and spend money. Even San Diego has new car and bicycle sharing programs with a couple of parklets being proposed. I believe this ‘Active Living’ trend has the most promise to resonate over a longer period of time because it connects the social, cultural and physical threads that shape the quality of our daily lives.

The Next Urbanism Lab is an ongoing series of posts exploring our built future. See everything to date here.

–Howard Blackson

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.