A Placemaking Journal

Life as I’d Like It To Be

Absorbing the Norman Rockwell exhibition at the Winnipeg Art Gallery over the past four weeks, it’s extraordinary to witness one artist chronicling one nation over seven decades, from 1916 to 1978.

For more than half of his career, Rockwell was constrained by racism that dominated the nation, forcing him to depict people of colour in subservient roles, if he wanted to publish in most circles. This is the timeframe and the images that many people think of when they think Rockwell. And it’s the majority of his body of work.

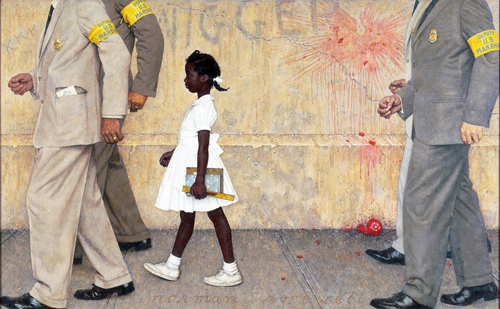

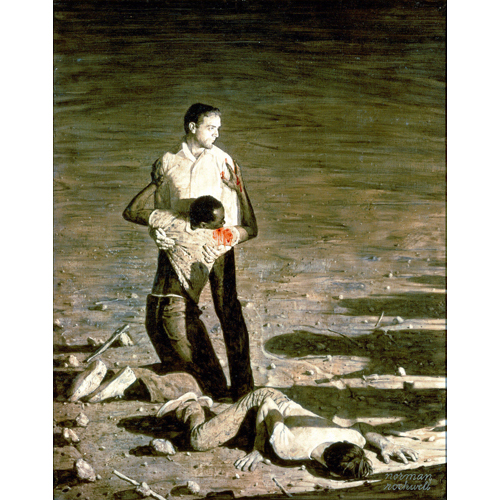

It’s liberating to watch him later tackle hard issues of desegregation and hate crimes, once society permitted meaningful dialogue. During the years of his constraints, Rockwell looks for the good in people, and celebrates what is working: family, connections, community, and humor.

Leading a challenging life himself, he says, “I paint life as I’d like it to be.” Somehow, in his constant looking for the good, he steers people toward hope. He reiterates and reinforces what is working. And eventually has the freedom to mourn what isn’t.

The Globe and Mail review of the Winnipeg show applauds a feel-good master’s complex message that still resonates in our age of anxiety. Being raised in Alabama, these images stick with me on a number of levels. The show is on until May 20, and I’ll be back to keep looking.

Reinforcing What Works

If you’re wondering what this has to do with placemaking, I’m getting to that. Within all challenging timeframes, there are certain ideals we quietly reinforce as a society, even when bigger issues lurk that we’re not addressing. During the times when there’s a lack of meaningful discussion on how to move forward, many people still resonate with these ideals, and reinforce them in some way or another.

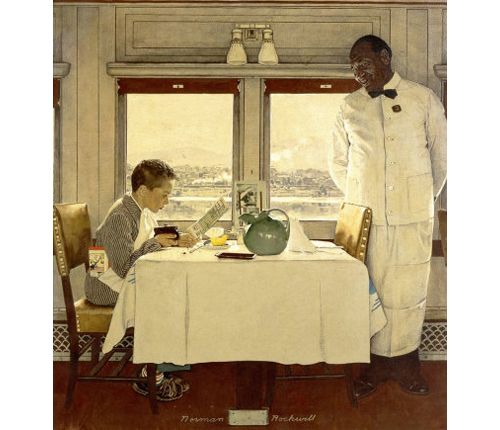

Whether it’s the African-American waiter’s fatherly smile toward the young white boy trying to figure out the appropriate amount of his first tip, in Boy in Dining Car. Or people lovingly caring for neighborhoods that are no longer legal to build. If most of our walkable, character-rich neighbourhoods burnt to the ground today, they’d have to be built back with wide, suburban streets and a separation of uses, thanks to the fact that we’ve legalized our love affairs with the automobile and suburbia.

The redeeming factor is, because people do love the character-rich places, many of them have been preserved, quietly celebrated, and fiercely protected by their residents. Not in a dissimilar way to how Rockwell reinforces family, community, and connections at a time when it was hard to address the elephant in the room.

Our Elephant

When society became more open to discussing and positively responding to issues of race in the ‘60’s, it was a decade or so after we began actively insulating ourselves from people different than us by white flight to the suburbs of the ‘50’s. Then later locking ourselves into gated communities in the ‘70’s and ‘80’s. A recent sorrowful event in a Florida gated community points to failures in this system.

While we’ve made great advances in the civil rights discussion, our very suburban development bylaws continue to make it harder for people to connect in a constructive way, and continue to make for mistrust that comes with not getting to know each other. Whether it’s people of different races, ages, backgrounds, or income brackets. Suburbia segregates by all of these.

We’ve discussed that here at length, in terms of charity, connectivity, social networks, resilience, and parenting.

The Idyllic Landscape

Despite demonstrating significant returns, historic urbanism is a frequent recipient of critiques about sentimentalism, similar to the art criticism of Rockwell in past decades. Just as Rockwell’s retrospective at the Guggenheim, the “temple of modernist art,” signaled a shift in viewpoint of the artistic community, the recent embrace of walkability signals a shift in the definition of livability.

While the average person on North America still spends 6.25 weeks every year in their car, we’re starting to resist what that means to our wallet with rising fuel prices, and to our lifespans with rising obesity. We’re starting to redefine livability in terms of quality of life (community amenities, active transportation, family time, social capital) instead of standard of living (size of house, number of cars, size of lot, earnings).

Similar to Rockwell’s “life as I’d like it to be,” Voltaire’s Candide struggles in his yearning for “the best of all possible worlds,” but lives through a satire riddled with caricatures and clichés. In the end, he settles for the conclusion that “we must cultivate our garden.”

It isn’t the architecture, or the urbanism, or inclusiveness, or the economy that will make the world right, but when all of those things are working together. It’s the patterns and connections that we’ve quietly reinforced as a society over time that hold both the meaning and the healing.

Both autonomy and connectivity are fostered in large part by the form of the built environment. And that lets us cultivate our garden.

–Hazel Borys

Endnotes

Boy in Dining Car, Norman Rockwell, 1946

Cover illustration for The Saturday Evening Post, December 7, 1946.

©1946 SEPS: Licensed by Norman Rockwell Licensing, Niles, IL.

From the permanent collection of Norman Rockwell Museum

The Problem We All Live With, Norman Rockwell, 1963

Illustration for Look, January 14, 1964

Licensed by Norman Rockwell Licensing, Niles, IL.

From the permanent collection of Norman Rockwell Museum

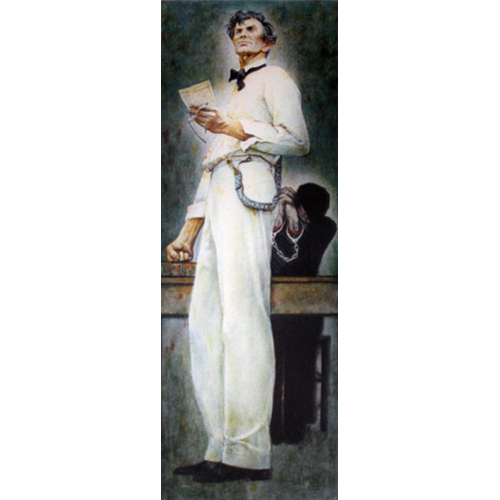

Lincoln for the Defense, Norman Rockwell, 1961

Painting for The Saturday Evening Post story “Lincoln for the Defense” by Elisa Bialk, February 10, 1962.

©1961 SEPS: Licensed by Norman Rockwell Licensing, Niles, IL.

Norman Rockwell Art Collection Trust

Murder in Mississippi, Norman Rockwell, 1965

Painting intended as the final illustration for Southern Justice by Charles Morgan, Jr., Look, June 29, 1965, unpublished

Licensed by Norman Rockwell Licensing, Niles, IL.

From the permanent collection of Norman Rockwell Museum

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.