A Placemaking Journal

Context is King: Can we pave our way to walkability?

Sidewalks are where walkability begins. But they are not, in themselves, walkability.

For decades, well intentioned communities have treated walkability primarily as an infrastructure problem. If only we could add sidewalks, stripe crosswalks, narrow travel lanes, and install curb extensions, then people would walk. And to be clear, those investments matter. Safety and accessibility are foundational. But in community after community, even where those basics are present, walking remains optional rather than instinctive.

The missing ingredient is not concrete. It’s context.

Access is Not the Same as Appeal

Architect and planner Steve Mouzon calls this missing quality “Walk Appeal.” He has written at length (here, here, here and here) about what makes a place compelling on foot — the measurable characteristics such as enclosure, frontage transparency, and block length, as well as the immeasurable ones: craftsmanship, rhythm, subtle complexity, and the invitation embedded in a well-shaped doorway or shaded stoop.

Walking is not simply a mode of transportation. It’s a sensory experience. If that experience is monotonous, people will minimize it. If it’s layered and engaging, people will extend it.

The automobile dominates not only because it’s fast, but because we have systematically stripped walking environments of the very qualities that make them interesting. When every street feels interchangeable, when uses are segregated, when buildings are set back behind parking fields, walking becomes something to endure rather than enjoy.

You can technically walk there. You just don’t particularly want to.

A Personal Lesson in Context

A year ago, I was forced into an unintended experiment. A serious leg injury required me to pause and then scale back my daily three-mile walk. As I recovered, I shortened my routes considerably. Before the injury, I routinely incorporated downtown into my loop — storefronts, shifting scenery, overlapping activities, the unfolding choreography of civic life.

But afterwards, with my range limited, I stayed within the neighborhood.

What I rediscovered was not dissatisfaction, but difference. Residential streets possess their own calm beauty, yet the visual dynamics change slowly. Similar setbacks. Repeating forms. Long stretches of single-purpose frontage. I found myself aware of distance in a way I hadn’t before. I spent the walk mentally tracking how far I’d gone and how much remained.

Now that I’m on the mend and downtown is back in the mix, something has returned: daily variation. Shop windows evolve block by block. A restaurant patio hums. A delivery truck interrupts the rhythm. The spatial enclosure tightens. Architecture shifts scale and detail. Without consciously intending to, I walk farther. My mind is engaged enough that the distance recedes.

The sidewalks in both environments are functional. The difference lies in the land use pattern surrounding them.

The Zoning Map Is the Real Design Document

This is where the policy critique becomes unavoidable.

The character of a place is determined first and foremost by land use planning. Before an architect draws a façade or a traffic engineer specifies curb radii, the zoning code has already established what kind of environment is possible.

Conventional Euclidean zoning — our default system for nearly a century — prioritizes the separation of uses. Residential here. Commercial there. Office somewhere else, with civic tucked into its own district. The result is predictability at scale, but also homogeneity at the block level. Entire swaths of community life become single-purpose landscapes.

In that context, even perfect sidewalks cannot manufacture the tangible and intangible sensations of “walk appeal.” They connect like uses to like uses. They offer safe passage through monotony.

Walkability is not undermined by a lack of paint or pavement. It is undermined by land use patterns that suppress variation.

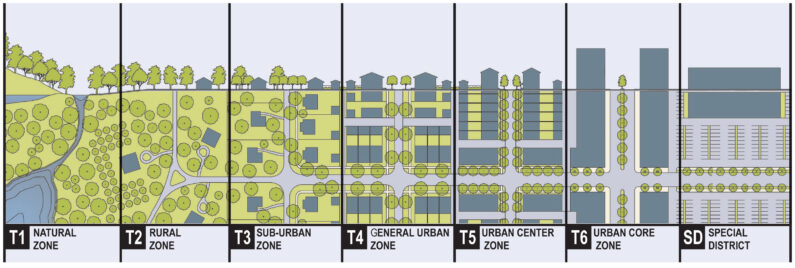

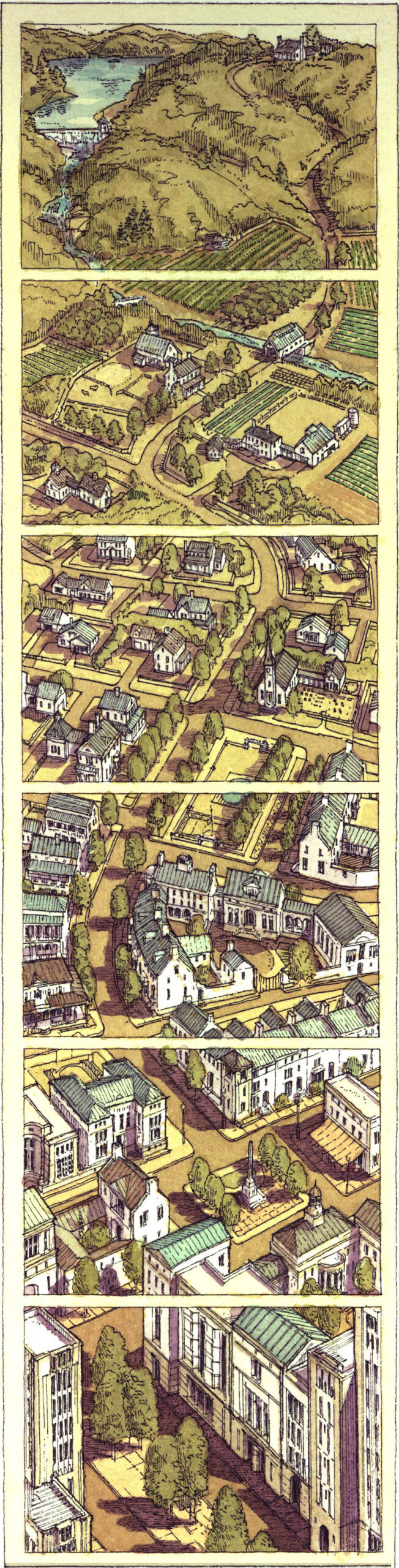

The Transect and the Logic of Nature

By contrast, Transect-based planning begins with a different premise. It organizes environments along a coherent gradient, from rural to urban center, ensuring that intensity, use-mixing, building form, frontage conditions, and street design reinforce one another.

Importantly, it does not seek to urbanize everything. It protects rural and natural areas precisely by concentrating appropriate intensity where it belongs. It acknowledges that context matters, and that different contexts require different spatial patterns.

There is something deeply intuitive about this gradient because it mirrors nature itself.

A walk in the woods is rarely monotonous. Even within a single ecosystem, the terrain shifts subtly. Light filters differently through the canopy. Understory plants change. Sounds vary. Microclimates emerge along ridges and streams. The variety is inherent in the context.

We are stimulated not by spectacle, but by layered complexity.

The same principle applies in well-structured urban environments. A properly formed urban center has storefronts, upper-story residences, civic buildings, shaded sidewalks, and varied frontages in close proximity. The edges are defined. The uses overlap. The experience unfolds incrementally.

In both cases — forest and downtown — the richness comes from context structured with internal logic. In nature, that logic evolved. In cities, it must be planned.

Conventional zoning disrupts the gradient. The Transect restores it.

The Cognitive Case for Complexity

We often speak about the physical health benefits of walking, and rightly so. But research increasingly suggests that walking in dynamic, varied environments may also support cognitive health. Exposure to spatial complexity, subtle social interaction, and changing visual cues appears to engage attention and memory in ways that uniform environments do not.

This should not surprise us. Humans evolved in complex landscapes, not in repetitive corridors of identical structures.

When we design communities that suppress variation at the block level and isolate uses at the district level, we are not simply shaping traffic patterns. We are shaping mental experience.

Sidewalks alone fail to compensate.

If We’re Serious About Walkability

If communities are serious about walkability, the starting point is not a sidewalk inventory. It’s a zoning audit.

What uses are permitted within a quarter-mile? Are daily needs interwoven or isolated? Do frontage standards encourage engagement with the street or retreat from it? Are block lengths short enough to create choice and variation?

Until those questions are addressed, infrastructure improvements will remain incremental at best.

We have spent decades attempting to retrofit walkability onto land use patterns designed for automotive separation. The results are predictably modest. We add decorative elements to fundamentally disconnected systems.

Sidewalks are necessary. They are foundational. But they are just one of many steps.

If we want a community where people instinctively choose to walk — not merely because it’s possible, but because it’s pleasurable and engaging — we must create the experience.

From Aspiration to Alignment

Across the country, communities are declaring walkability as a goal. They adopt Complete Streets policies. They commission pedestrian master plans. They fund streetscape enhancements. These are meaningful steps.

But unless land use policy aligns with those aspirations, the ceiling remains low.

Real walkability requires reforming the underlying code: allowing mixed-use by right, legalizing missing middle housing in appropriate contexts, reducing or eliminating parking mandates that push buildings away from the street, shortening block lengths in new development, and calibrating frontage standards to encourage human-scaled engagement.

In other words, it requires shifting from use-based separation to form-based coherence.

That’s not about making every neighborhood an urban center. It’s about allowing each context — rural, neighborhood, town center — to function according to its inherent logic, with enough internal diversity to sustain daily life on foot. The Transect provides that framework. It protects what should remain natural and concentrates intensity where it supports community vitality.

Walkability is often framed as a lifestyle preference. In truth, it’s a policy outcome.

If we want communities where walking feels natural rather than forced, engaging rather than obligatory, we must align our vision, our standards, and our zoning around that outcome.

Sidewalks will follow. Context must lead.