A Placemaking Journal

Mixed-Use: It’s not a building type, it’s the DNA of human settlement

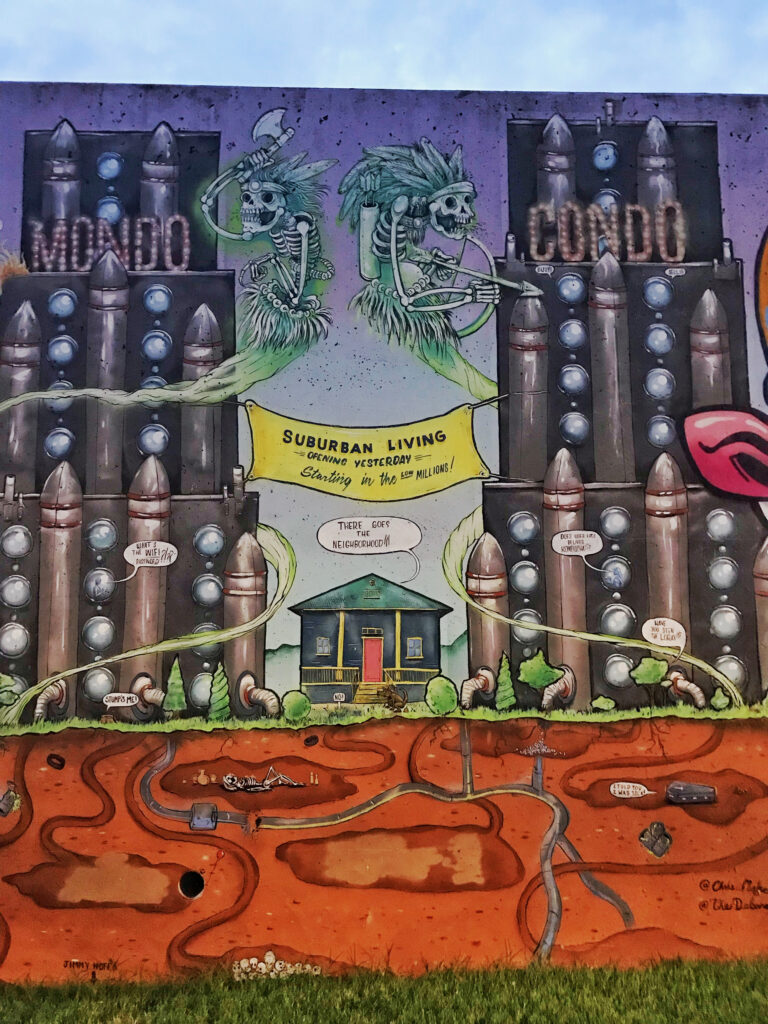

There’s a mural along Atlanta’s BeltLine that manages, in a single frame, to pack in just about every misunderstanding plaguing 21st-century urbanism. Two skeletal warriors swoop through the sky above rows of chrome-clad condo towers, pipes and ducts sprouting like some dystopian botanical garden. At the center sits a lone single-family bungalow, plucky and defiant, practically glowing with nostalgic righteousness. Stretched above it, between the towers, in large hand-lettered sarcasm is a marketing banner with the phrase: “Suburban living — opening yesterday, starting in the low millions!”

Which is funny, of course. And also not.

The mural wants to indict the rise of denser, mixed-use development, the very types of environments in which people throughout history have always lived, worked, traded, worshipped, argued, fallen in love, and raised their children. But because many of the people filling these new homes are arriving from decades of suburban exile, the mural assigns their identity to the buildings themselves. The form becomes suspect because the newcomers are unfamiliar. “Suburban living,” it sneers, as it celebrates the most suburban building type ever invented: the detached house on an island of lawn.

Don’t get me wrong. If the little yellow banner said “Profit over people” or “Displacement without conscience” or anything else making the very defensible point that there exists powerful forces often remaking the landscape without consideration of the most vulnerable, it would be worthy of attaboys rather than scrutiny. But that’s not what’s happening here.

This is the irony we swim in now. Mixed-use neighborhoods, a form that has defined human settlement for thousands of years, now framed by critics as somehow anti-urban.

How we got here

For about 50 years, the planning world has been trying to claw its way back to patterns humans have relied on since the first time someone said, “Let’s set up camp and stop walking for a while.”

Grappling with the consequences of the suburban experiment, the term mixed-use entered the conversation as siloed planner-speak. It then evolved into nomenclature for financing and development products. Today it’s a marketing buzzword, used as liberally as “artisan” or “farm-to-table.” Anything with apartments over a coffee shop, no matter how disconnected or auto-dependent, gets the label.

But mixed-use is not a buzzword. It’s not a typology. And it certainly isn’t a fad.

It’s the default operating system of human civilization. Everywhere. Across cultures, eras, climates, religions, and economic systems.

If you could plot humanity’s history of settlement on a timeline, the 20th-century American experiment in rigid, single-use separation — suburbs here, offices there, shopping somewhere else — wouldn’t even register as a blip. It’s the anomaly. The aberration. A short-lived divergence enabled by cheap land, cheap gas, and a lot of wishful thinking about how communities actually work.

Before “mixed-use” there was just everyday life

What we now present as designations on pastel-colored land-use maps used to be nothing more than how towns functioned. You didn’t separate daily needs; you integrated them because walking across town three times a day was time consuming and unnecessary, and taking a chariot to daycare wasn’t a thing.

The butcher lived next to the tailor who lived above the tavern that sat across from the carpenter. Residents didn’t think of it as planning. It was simply a reflection of how humans instinctively cluster around the exchange of goods, services, faith, and social life.

Mixed-use wasn’t a goal. It was the natural byproduct of living in community.

Even the patterns we’re now quick to label “European” or “charming” or “traditional” follow this logic. As do the hut clusters of the Pacific Islands, the medinas of North Africa, the rural villages dotting the Japanese countryside, and more. Different shapes, same idea: keep the pieces of daily life close together.

That’s the DNA. That’s the inheritance.

Then came the Big Separation

America’s brief love affair with separated-use zoning rewired our expectations. We normalized the notion that “living here” and “doing things somewhere else” was both desirable and virtuous.

Add in cheap energy, federal subsidy, and the post-war chase for convenience, and we convinced ourselves that distance was a feature, not a bug.

But that worldview aged poorly. It gave us traffic. It gave us 45-minute commutes to go six miles. It gave us places where the nearest gallon of milk requires a vehicle and children need chauffeurs just to see their friends. It also gave us social isolation, because when everything is spread out, the simple act of running into your neighbors becomes a statistical improbability.

The return — and the misunderstanding

So when cities began experiencing real renaissance, wherein people rediscovered the joy of proximity and the sanity of convenience, the comeback was inevitably messy. Developers raced to build what the market clearly wanted. Capital followed. Former suburbanites flocked to new walkable districts. Marketers slapped the phrase “mixed-use” on anything with a retail wrapper.

And existing residents, understandably wary of rapid change and rising prices, needed someone to blame. So the new buildings became the villains. Not just for their height or design, but for the people inside them: the “others” who weren’t here before.

That’s how we get murals calling dense urban housing “suburban.” That’s how we end up with neighbors arguing that the Platonic ideal of a city street, ground-floor commerce with living above, represents some existential threat.

It’s a development Whiplash Effect. Because traditional urbanism disappeared long enough to be forgotten, its reappearance feels like an intrusion rather than a restoration.

Mixed-use isn’t a building type, it’s a settlement pattern

One of the biggest misconceptions is that mixed-use refers to a vertical stack: shops below, homes above. That’s one expression, sure, but it’s hardly the whole story.

Mixed-use is best understood horizontally, with different buildings playing different roles, contributing to a unified ecosystem. A neighborhood where the bakery is next to apartments is mixed-use. A block with offices on one end and townhomes on the other is mixed-use. A street with a barbershop, a taco stand, a daycare, and a handful of bungalows is mixed-use. And so are multiple blocks comprised solely of residential housing but walkable to a neighborhood center or edge corridor.

It’s not about the building. It’s about the pattern.

It’s about enabling a life where daily needs cluster close enough that people can walk, bump into one another, and form the weak ties that eventually become the strong ties that ultimately become community.

The quiet truth beneath the noise

So yes, the mural is clever. But it gets the story backward. Mixed-use isn’t a suburban invasion. It’s the antidote. It’s the very thing cities have always offered, the thing that made them cities in the first place.

What we’ve been witnessing isn’t the rise of some newfangled trend. It’s the re-emergence of the oldest idea in urbanism: Keep the important stuff close. Share space. Live among others. Build community through proximity.

If that feels unfamiliar or threatening, it’s only because our 20th century deviation lasted longer than the memory of what cities and towns actually are.

Mixed-use isn’t the future. And it’s not the past. It’s simply the way humans live when they’re allowed to live together.