A Placemaking Journal

Climate Adaptation: A weather report

This is a case study of the application of Scott’s argument that will be presented at the upcoming virtual Congress, CNU28, during the Wednesday, June 10, 2:30pm EDT session, New Tools for Urban Resilience, as well as part of our ongoing series in support of urbanist COVID-19 policy discussions.

Among the lessons the COVID-19 crisis and the protests of the death of George Floyd have hammered home are those connected with, first of all, recognizing vulnerabilities, then having a plan to overcome them before the threats are upon us. We’d be wasting this unwelcome opportunity if we didn’t apply what we’ve learned to building resilience capacities in the face of climate change. The current crises are emphasizing how essential it is to plot a path for adaptation after a disturbance, stress, or adversity.

Community resilience emerges from four primary sets of adaptive capacities: social capital, information / communication, economic development, and community competence. Community competence are the collective action and skills for solving problems and making decisions, which stem from collective efficacy and empowerment. Knowledge is power, particularly if we act on what we know.

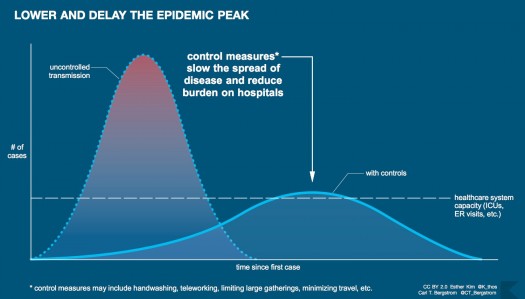

Just as surgery-ready types of hand washing, wearing masks, gathering outdoors, and staying a non-communicable distance apart can lower and delay the pandemic’s second peak so that our healthcare system has a better chance at staying near capacity, thinking through the impacts of sea level rise to potential climate refugees can help us get ahead of the curve in the future.

Climate Adaptation—A Weather Report

The evidence is clear: in the U.S., climate change is driving relocation. It’s time to help cities in less-exposed places plan for receiving and welcoming permanent climate “refugees.”

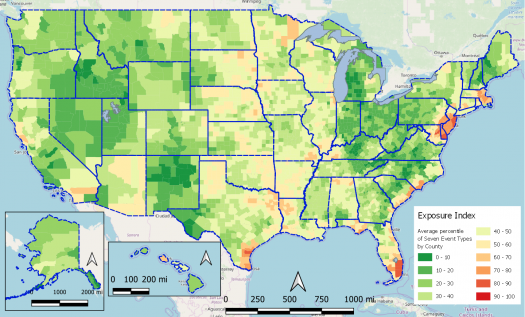

We mapped which places are exposed to what kinds of extreme weather over time. Standard climate-change references, such as the U.S. National Climate Assessment, is very far from our ideas of “local,” “community,” and “urban,” making the sorts of conversations usually we have here cumbersome.

Weather Service data shows 55 discrete types of severe weather, from 1997 to today. For 2009-2018, we identified 616,312 “severe weather” events associated with one-or-more counties, and grouped these into 7 event types (Heat, Wildfires, Drought, Tornados, Cold, Hurricanes and Storm Surge, and Coastal and Lakeshore Flooding), then graded all 3,142 U.S. counties on relative frequency of extreme weather.

Our map shows some places are riskier than others. During that period, Cuyahoga County (Cleveland) had 8 severe events (1 tornado and 7 extreme cold spells) while Miami-Dade County had 136 (6 extreme heat spells, 54 droughts, 10 tornadoes, 2 cold spells, 5 hurricanes, and 49 flooding events). Cuyahoga had less than 1 extreme event per year on average, while Miami-Dade had 14. Looking at the national distribution, the Ohio county is at a low 15th percentile, while the Florida county is at a very high 81st percentile. Hennepin County MN had 15 events—6 extreme chill, 5 extreme heat and 4 tornados, ranking 1593/3142 and the 49th percentile.

Twin Cities Case Study—Looking Closer Over a Larger Area

With the Congress for the New Urbanism that had planned to head to Minneapolis and St. Paul next week but now will be gathering virtually, we are taking the Twin Cities as a case study, which scored in the middle of this distribution. The combined exposures for all 7 severe weather types are in the 50th-60th percentile.

Area counties experienced extreme heat 1-2 times per year; droughts every 1-2 years; extreme cold and wind chill 1-2 times per year; tornado strikes 1-2 times per year, no hurricanes, storm surges nor tides; and no coastal or lakeshore flooding. Surface flooding results from rapid snowmelt plus occasional heavy rains.

Event frequencies vary by weather type and by the definition of “region.” Minneapolis and St. Paul are each within a single county, Hennepin and Ramsey. From a weather forecasting POV it’s much larger; for this study we used the 16-county Combined Statistical Area or CSA.

In the CSA 19 of NOAA’s 55 severe weather types regularly occurred. In 2009-2018, there were 2,664 severe weather events, 266 per year or 22 per month. The high count was 401 events in 2012 and the low was 154 in 2015. 1,867 or 70 percent of total events involved very high winds including tornados and/or battering/clinging forms of precipitation such as hail and/or roof-collapsing weights of snow and rain; 597 or 22.4 percent involved extreme winter chills or storms; 135 or 5.1 percent were floods and flash floods; and 45 or 1.7 percent involved excessive heat.

Which places are most exposed to severe weather? Of all 3,142 counties, Hennepin ranked 1,593, and Ramsey ranked 1,717. While those ranks seem low, they contain the bulk of this CSA’s concentrated populations, buildings, and economic assets at risk. Contrasting risk in the Twin Cities to the Miami area, Miami-Dade came in at 15th highest, Palm Beach at 31st, and adjacent Broward County at 35th; while Cuyahoga County came in at 2191, respectively.

Is this region a potential “welcoming” area for likely US domestic climate “refugees”?

• The City of Minneapolis is a leader in affirmatively welcoming international migrants including Somali and Hmong refugees. St. Paul is an active member of Welcoming America (see below).

• Minneapolis recently up-zoned single-family lots for higher densities. Hennepin County has sponsored numerous form-based codes to make way for transit-oriented development and Blue Line expansion. The region prides itself on collaborative planning for transportation, sanitation, and stormwater management; Minneapolis stormwater management fees are rebated if owner has installed effective on-site green infrastructure.

• In 2019 The American Council for an Energy Efficient Economy ranked Minneapolis 4 and St. Paul 31 out of 76 large cities on their climate and energy strategies

• Resilience efforts are included in climate action planning by Minneapolis and by Twin Cities Metro government. The region is a leader in shared infrastructure on a community scale with a both legacy and modern district energy systems in place or developing, and working partnerships between neighborhoods, cities, counties and the State for green infrastructure experiments.

• The region is known for its regional tax-base sharing system and has also invested in a modern light rail and bus network, starting in 2006. The most recent LRT line’s stations in neighborhoods between St. Paul and Minneapolis each participated in equitable TOD planning over a decade-long period resulting in accountable commitments to affordable housing, locally-owned businesses, and culturally-rooted enterprises.

• While the Transit Performance Scores for Minneapolis and St. Paul are a respectable 8.3 and 7.7 out of 10, the region-wide score of 4.2 reflects the need for planning attention in the area’s far-flung suburbs. Nationally, the transit quality for Minneapolis ranks 15th, St. Paul 25th, but the metro area ranks 35th. Some of this will be addressed by new extensions. A recent study of potential location-efficient freight options identified over 100 sites for rail-enhanced shipping or Cargo Oriented Development, which can also contribute to the green infrastructure inventory.

• Minneapolis is included in the Rockefeller Foundation’s 100 Resilient Cities. Support for suburban adaptation is offered by the Center for Urban and Regional Affairs Resilient Cities Project at UMN, and by the Resilient Cities and Communities Coalition. The Metropolitan Council (itself a metropolitan government) provides guidance for developing local plans for both mitigation and adaptation.

• The region is one of the Midwest’s top two economic performers, but a persistent Twin Cities poverty rate of 20 percent indicates more is needed to both raise incomes and lower the cost of living.

These observations of recent history and risks will change as weather patterns intensify or if the actions of local stakeholders are diminished. There’s an engaged regional grant-makers network supporting an equally active network of civic innovators. How to sharpen planning to result in accelerated investments in both major and leaner initiatives is a front-line challenge.

Funders skillfully leverage national sources to support such goals, e.g. both Minneapolis and St. Paul won inclusion as 2 of the 25 cities in the Bloomberg Foundation American Climate Cities Challenge. So far, their plans are more focused on mitigation than adaptation. Urban Heat Island mitigation will require tree canopy restoration among other green infrastructure strategies.

Much as mariners needed something better than “hugging the shore” or “any port in a storm” to guide risky navigation, our climate haven-finding art needs an upgrade.

Maps of exposure are a first step. Next, maps of readiness should cover both physical characteristics, such as area permeability versus excessive paving, and social capacity, i.e. ability to adopt and invest in resilience and adaptation. This latter category includes zoning and form-based code adoption, further climate action and resilience strategies, and further affirmative migration strategy.

One indicator of affirmative migration strategy is membership in Welcoming America, a growing network of 200 cities with a formal protocol tracking level of commitment and progress toward that goal.

Map additions will be prepared, one from a project evaluating quality of municipal adaptation using studies covering 3,000 local efforts, another from work identifying State barriers to and assets for local assistance, and a third reviewing the history of efforts to achieve collective efficacy and alignment whether for recovery from major disruptions or from efforts to plan ahead effectively (e.g. WW2 relocated over 10 percent of the U.S. population in non-military assignments in less than 5 years).

Keeping Score on These Discrete Events Supplements Current Climate Change Assessments

A NOAA-funded team identified these Twin Cities climate trends–

• Rising temperatures: Temperatures warmed by 3.2°F from 1951-2012, faster than the national and global rates. Average low temperatures have warmed much faster than high temperatures.

• Longer freeze-free season: The length of the freeze-free season (growing season), increased 16 days from 1951-2012.

• More precipitation: Total precipitation increased 20.7% (5.5 inches), from 1951 through 2012. Fall and spring increases exceed 25% (1.9 and 1.5 inches, respectively).

• More heavy precipitation: The number of very heavy precipitation events has increased by 58.3% (comparing the 1951-1980 total to the 1981-2010 total).

That average temperature, 3.2ⷪ F = 1.78ⷪ C, already within the danger zone of 1.5ⷪ – 2ⷪ C signaled by the IPCC and in the Paris agreements.

The NWS archive of news reports on extreme weather put a community face on these statistics, as does a search by “The Great Flood of ____” or a search for booklets with such names in bookstores and libraries.

Severe weather signatures and county-level rankings do tell a story. The event frequency of 266/year is significant. Events dominated by high winds and structure-stressing precipitation such as hail/heavy rain/snow, and by inland flooding, along with an increase in excessive summer heat, is an issue for the area’s-built environment & population. Yet the ability to adapt to such changes is potentially within the means of the region’s communities at appropriate scales, and on that criterion, could make this region’s communities “safer havens” for domestic climate refugees.

Welcoming as a Bridge to Somewhere

Historically, settlements grew at points of landing and migration followed inward. In the U.S., the population centered in Maryland; it spread out and today is in SW Missouri. Households in 1790 had 6 persons each, today’s national average is 2.5. The percentage of households with only 1 or 2 persons grew from 40 percent in 1960 to two-thirds today. In the name of protection from nuclear threat, post-WW2 policies accelerated dispersal.

Sea Level Rise, and high-wind weather events inland from the Atlantic & Gulf coasts alone could trigger WW2-scaled relocation. A climate-risk-enabled affirmative, welcoming-cities strategy could repair the damage from those policies and trends and right-size what results. These maps raise the question: have we been migrating to the riskiest places? They also raise the questions, what needs to be done in the less-exposed locations to make those both climate-change and resettlement-ready, and how do these opportunities vary by scale? We don’t have forever to decide, so which places offer the lowest-risk, & most-streamlined opportunities?

-– Scott Bernstein, Peter Haas, James DeBettencourt

Scott is Founder and President Emeritus of the The Center for Neighborhood Technology (CNT). Pete is CNT’s chief scientist and Jim is a planner/engineer/data scientist supporting CNT. The CNT is the national non-profit that has pioneered ways to quantify the advantages of linking transportation, land use and housing strategies with economic development and community affordability. It is the leading national provider of web-based analytic and data access tools for local area planning intended to meet the triple bottom line of improved quality of life, improved economic quality of place, and environmental resilience. CNT is a winner of the 2009 MacArthur Foundation Award for Creative and Effective Institutions, and Planetizen lists Scott Bernstein as number 27 in its poll identifying the Top 100 Urban Thinkers of the past century.

Resources

• “D.C. During WW2,” Scott Bernstein

• DIY City: The Collective Power of Small Actions, Hank Dittmar, Island Press, March 2020, Island Press

• American Warming: The Fastest Warming Cities and States in the U.S., Climate Central at https://www.climatecentral.org/news/report-american-warming-us-heats-up-earth-day

• Can It Happen Here? Improving the Prospects for Managed Retreat by Cities, Peter Plastrik & John Cleveland, March 2019 at http://lifeaftercarbon.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Managed-Retreat-Report-March-2019.pdf

• Can Large-Scale Government Be Part of the Solution? Heather Cox Richardson, Meg Jacobs, Gregg Hercken, Charles Meier, Harry Lambright, Alliance for Climate Protection May 14-15 2008

• “Climate Extremes and Compound Hazards in a Warming World,” Amir AgaKouchak et. al. Annual Reviews of Earth and Planetary Science, 10:26, May 2020, Online advanced copy February 7 2020

• Evidence of Urban and Lake Influences on Precipitation in the Chicago Area, Stanley Changnon Jr., J. of App. Meteorology 18:10 Oct 1980 pp. 1137-1159

• Historical Climatology: Minneapolis-Saint Paul, Minnesota, NOAA/GLISA/U of MI Climate Center/MSU, at http://glisa.umich.edu/media/files/Minn-StPaulMN_Climatology.pdf

• Home Front USA: America During WWII, Allan W. Winkler, Harlan Davidson Press, 1986

• Mapping Climate Exposure and Resilience, Scott Bernstein, Peter Haas, James DeBettencourt, forthcoming 2020

• “Modeling migration patterns in the USA under sea level rise,” Caleb Robinson, Bistra Dilkina, Juan Moreno-Cruz, PLOS One, January 22, 2020 at https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0227436

• MSP Thrive 2040 Regional Plan, Metropolitan Council of the Twin Cities at https://metrocouncil.org/Handbook/Plan-Elements/Resilience.aspx

• National Weather Service – Archive of Post-Storm Articles, Twin Cities MN, at https://www.weather.gov/mpx/events

• “Precipitation Change in the United States,” IPCC, 2017, Chapter 7 at https://science2017.globalchange.gov/chapter/7/

• Shrinking Cities: Understanding Urban Decline in the U.S., Russell Weaver, Sharmistha Bagchi-Sen, Jason Knight, Amy E. Frazier. Routledge 2017

• Sinking Chicago: Climate Change and the Remaking of a Flood-Prone Environment, Harold Platt, Temple U. Press, 2018

• The City and the Coming Climate, Brian Stone Jr., Cambridge U. Press, 2012

• The Haven-Finding Art: A History of Navigation from Odysseus to Captain Cook, E.G.R. Taylor, Hollis & Carter, London 1956

• The Urban Fix, Doug Kelbaugh, Routledge Press 2019

• Tunnel Vision: Did Chicago Build the Wrong Solution? Henry Grabar, Slate magazine, January 2, 2019 at https://slate.com/business/2019/01/chicagos-deep-tunnel-is-it-the-solution-to-urban-flooding-or-a-cautionary-tale.html

• War and Society: The United States 1941-1945, Lippincott, 1972

• Welcoming America, www.welcomingamerica.org

• “Where America’s Climate Migrants Will Go as Sea Levels Rise,” Linda Poon, CityLab, February 3, 2020 at https://www.citylab.com/environment/2020/02/climate-change-migration-map-sea-level-rise-coastal-cities/605440/

The best summary of such larger regional trends is at https://www.sciline.org/quick-facts/ with messaging tips and contact info for journalists.

Sea Level Rise is a long-term climate change outcome caused by both polar ice cap melting and by the expansion of oceans from increased heat, and therefore is not counted directly as a “severe weather event.” Storm surges and hurricanes are discrete weather events, and they are both amplified by the increase in sea levels to date, resulting in so-called “king tide” events at ocean-marine coast interfaces.

The adjacent map is based on these 7 composite measures, as are the statistics in the next paragraph. In the detailed section on the Twin Cities area below, we counted events as the sum of all 19 types of repeat weather events in the region, hence the second method results in much higher scores of events.

The relevant NWS office for the Twin Cities region is the Minneapolis/Chanhassen or MPX facility, which covers the lower half the state of MN excepting greater La Crosse and part of WI.

NOAA classifies a storm as “severe” when it produces wind gusts of at least 58 mph and/or hail one inch in diameter (about the size of a quarter) or larger and/or a tornado. NOAA and NWS definitions of all 55 “severe weather” types plus sub-types are at “Storm Data Preparation,” March 23, 2016 at https://www.nws.noaa.gov/directives/sym/pd01016005curr.pdf. The inventory relies on both automated sensing and input from trained spotters; for a critique of the system, see Authors of the Storm: Meteorologists and the Culture of Prediction, Gary Alan Fine, U. of Chicago 2007, pp. 182-194.

The Twin Cities CSA has 0.2 percent of the US land area, but experienced 0.4% of the total severe weather events in the decade.

USDA urban forest researchers found that tree canopy coverage drops by 0.22 percent and impervious area increases 0.15 percent annually in Minneapolis; see https://canopy.itreetools.org/resources/Tree_and_Impervious_Cover_change_in_US_Cities_Nowak_Greenfield.pdf and https://database.aceee.org/city/minneapolis-mn https://database.aceee.org/city/saint-paul-mn.

See page 18 of Vibrant Places in About Community, Not a Commute: Investing Beyond the Rail, Final Report Published by the Central Corridor Funders Collaborative, 2016 at https://www.spmcf.org/uploads/general/What-We-Do/Files/CCFC/CCFC2016-LegacyReport-Final-Web.pdf and page 22 description of the Irrigate Project Rankings at https://alltransit.cnt.org/rankings/.

2019 analysis of 113 industrial “districts” in the Minneapolis-St. Paul CBSA that had at least 60 acres available with two or more modes of freight transportation available, scored also on various marketplace and worker accessibility measures; Center for Neighborhood Technology forthcoming.

In National Weather Service-speak, “heavy” before a type of precipitation indicates high force sufficient to damage buildings, e.g. “heavy rain” or “heavy snow”.

Climate Central’s review of weather reports from 1970-2018 found that average temperature in Minneapolis increased by 3.7 degrees F or 2.06 degrees C, possibly showing acceleration; Minneapolis ranked 14th on this measure out of 246 for “America’s fastest warming cities.” Higher temperatures drive higher levels of chaotic weather (e.g. those wind events) and precipitation.

The National Weather Service maintains a page titled “NWS Twin Cities Archive of Post-Storm Articles” at https://www.weather.gov/mpx/events; see also “When 100-Year Floods Happen Often, What Should You Call Them?” at https://www.mprnews.org/story/2019/05/08/flooding-record-mississippi-river-stpaul. Several area flooding records have been set over recent years there, one for longest duration, and others triggered by snow melt compounding rainfall.

–Scott Bernstein, Peter Haas, and James DeBettencourt

Scott is Founder and President Emeritus of the The Center for Neighborhood Technology (CNT). Pete is CNT’s chief scientist and Jim is a planner/engineer/data scientist supporting CNT. The CNT is the national non-profit that has pioneered ways to quantify the advantages of linking transportation, land use and housing strategies with economic development and community affordability. It is the leading national provider of web-based analytic and data access tools for local area planning intended to meet the triple bottom line of improved quality of life, improved economic quality of place, and environmental resilience. CNT is a winner of the 2009 MacArthur Foundation Award for Creative and Effective Institutions, and Planetizen lists Scott Bernstein as number 27 in its poll identifying the Top 100 Urban Thinkers of the past century.

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.