A Placemaking Journal

Climate Change Update, Part I: The End is Near (Really)

Back in 2011 when we were emerging from the Great Recession, I wrote an “End Is Near” post about the chance to make use of the crisis.

When you run out of all options except the ones that force you to think big,” I wrote, a little panic could be a good thing: “We are about to be freed to innovate, to become heroes even, by being stripped of comfortable delusions. Chief among them: Faith that somebody else will pick up the tab.”

The argument is unoriginal. Every big project requires a sense of urgency. Take, for instance, the project coming together in wrap-up episodes of “Game of Thrones,” where the threat of ice zombies wiping out all of civilization motivates feuding warlords to combine their forces in an army of the living to fend off the army of the dead. See also: Samuel Johnson’s 18th century observation about how “the prospect of a hanging in a fortnight wonderfully concentrates the mind.”

The bad news for us after the Great Recession and maybe for the assembled GOT forces in Winterfell is that a critical mass of heroes and heroic ideas doesn’t always materialize. Delusions persist. Especially when the zombies aren’t yet marching on the neighborhood.

Enough of us felt the Great Recession and its potential for disrupting lives to allow for a temporary breach in barriers to boldness. Rival political parties and the outgoing and incoming presidents signed off on an emergency agreement to pump hundreds of billions of dollars into the economy to avoid a slide into something worse.

In 2019, anxiety has metastasized. But now it’s unmoored. The things we have ample reason to fret over, including growing inequity issues unaddressed by the recession-era bailout, loom in times and places uncertain. We may acknowledge that some people in some places are going to pay terrible prices for our dithering. But when and where and who? The uncertainty permits a slow-walk from denial to doing something.

From a political perspective, stalling plays to our biases. We prioritize today’s emergencies over ones that seem far off. Big, scary stuff demands strategies at scale, like rounding up an army of the living. Which is no small task in an economy designed around short-term profits and for governments dependent on consent of the governed.

“It requires voters to accept ‘up-front costs that, if successful, will stave off never-to-be experienced long-term damage — policy for which election-oriented politicians can easily foresee receiving blame instead of credit.’”

That’s from a 2018 Washington Post opinion piece by Charles Lane. The interior quote is from public opinion researchers Patrick J. Egan of New York University and Megan Mullin of Duke University.

As you might suspect, Lane is talking about the ultimate high-risk example of political paralysis: The struggle to deal with the global impacts of climate change. Aggressive strategies to limit long-run damage, like slashing carbon emissions, he says, again quoting Egan and Mullin, “is a cause that ‘has no core constituency with a concentrated interest in policy change,’ while ‘a majority of people benefit from arrangements that cause’ climate change.”

This is a less than perfect time to be dealing with this stuff. Polarized politics already prevent us from addressing immigration, infrastructure, affordable housing, aging demography, health care, and other issues, each with their own steep price tags and accruing interest. Climate change won’t just add to the to-do list; it promises a multiplier effect, amplifying and accelerating crises already straining our capacities.

Retired Colorado State University professor and writer SueEllen Campbell, curator of 100 Views of Climate Change and a regular contributor to Yale Climate Connections, invites us to consider what we should already know:

“Just think about how disruptive wild weather can be: How the shelves of stores empty out of food, water, flashlights, batteries. Filling stations run out of gas. Roads are closed or jammed to a standstill. Power, phones, the internet — all out. Homes become flooded with toxic sludge or turned to ash piles and melted metal after out-of-control fire. Flooded farm fields. Frozen or flooded livestock. Fish without water. Whole towns brought to their knees. Businesses bankrupted by the costs of disruption and recovery. Helping agencies out of funds and staff. People dying because their bodies can’t cope with extreme heat or cold. Or they can’t move faster than wildfire or floods.”

That’s the here and now. “All these things are going to get worse as extreme weather increases,” says Campbell. “There are the things that happen more gradually”:

“Rises in hay fever, asthma, disease-carrying mosquito bites, heat stress on unborn babies and the elderly. We’ll have to rethink what plants will grow in gardens and farm fields, how to plan future access to safe drinking water, if it will be safe to travel to places where resources are even more strained.”

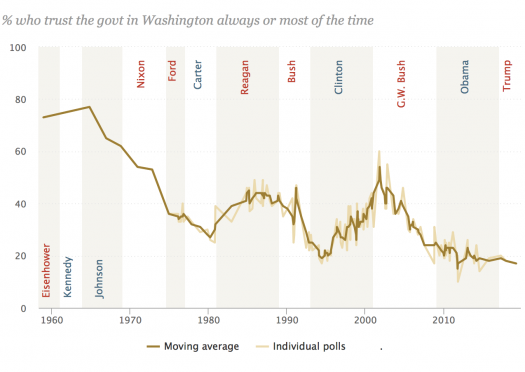

Add to that disruptions of economies at every scale and the social and political challenges of massive migrations of people away from danger zones to areas that may escape direct impacts of climate change but lack the resources to accommodate so many newcomers. The only sector of society specifically charged with figuring out and implementing comprehensive solutions to large-scale, long-term problems is government, which is currently hobbled by record low trust from those required to consent to solutions that are likely to inconvenience them.

No wonder, says author David Wallace-Wells, “It is O.K., finally, to freak out.”

The disruptions ahead, Campbell reminds us, “will come with questions for our hearts, how wide they will open, how well they will heal. They will test how imaginative we can be in creating new ways of thinking and doing and taking care. In summoning the courage we’ll need in going forward.”

In a second post, we’ll talk about ways the escalating sense of urgency is motivating some to address those questions — if not at the national and global scales that will ultimately be required, then at least as a demonstration of a path in that direction.

–Ben Brown

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.