A Placemaking Journal

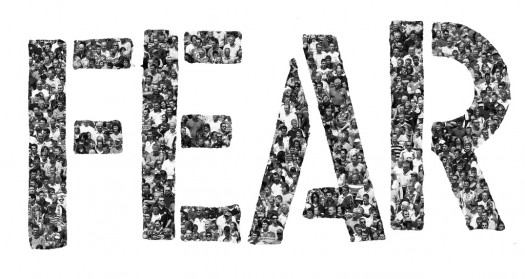

The Fear Freak-Out: Now in neighborhoods near you

The times, shall we say, are not ideal for that conversation we keep talking about.

You know, the conversation we feel we need whenever something scary happens. That ever-elusive, rational talk that includes everyone and ends with, if not a group hug, then at least a group understanding.

If we’re fortunate enough not to have been on the front lines of daily battles with poverty, racism and diminished opportunities of all sorts, we might not have seen this coming. At least not this fast and not at this rage setting. No need to evoke the Trump Moment by itself, or the unsettling news from Europe and the Mideast, or even the wave of recent violence in American cities. It’s all that together, linked and metastasized in our imaginations and jamming our coping circuits. Uncertainty abounds. And from uncertainty comes fear.

Are the Others coming to hurt us and take our stuff? Should we retreat to the bunker? Convert the kids’ college funds to gold bars?

All that’s apparently on the table. But a nuanced conversation about reshaping policy to protect the vulnerable and spread opportunity more broadly? Ha!

How fear is playing out in community and regional planning caught a lot of us by surprise. We should have known something more ominous was supplying energy to the anti-Agenda 21ers, who built a movement around fear of an international conspiracy to take over American institutions and communities via a relatively unknown United Nations resolution — Agenda 21. (For a look at how Agenda 21 affected planning policy in a South Alabama county, check out this 2014 NextCity post).

When the anti-Agenda 21ers first started showing up at planning meetings, city and county staffers often had to Google “Agenda 21” to figure out what the heck they were talking about. Soon, planners found themselves before a crowd of vocal skeptics and the elected officials they intimidated. No, they heard themselves having to explain, this modest comp plan draft was definitely not a copy-and-paste document from the U.N. handbook, the one designed by foreigners and abetted by federal agency co-conspirators to seize private property and herd citizens into urban ghettos.

That movement is running its course, at least in communities in which growth pressures inspire development that people resent. When resentment reaches a certain point, citizens tend to demand government intervention in the form of more restrictive rules on what gets built and where. It turns out fear of what may happen next door or down the block trumps fear of what the United Nations might be up to. But if NIMBYism sometimes rescues planning from the grip of one sort of irrational fear, it also hobbles planning with another version.

In the most appealing places — particularly urban neighborhoods with high potential for walkability, transit access and mixed use — fears of gentrification threaten to lock communities in a polarized debate that exacerbates the problems that planning and design can help ameliorate.

Opponents of the narrowest interpretation of gentrification see themselves as defenders of community character. And their arguments are appealing: When new residents and new businesses move into an old neighborhood, they’re disrupters. Rents and property values (and therefore taxes) go up. Some older residents move out. Others are stuck without the resources to move elsewhere or to afford to fully participate in the social and economic life of the “new” neighborhood. It becomes a different place.

Resentment builds. And again, the demand is put to government to use its regulatory powers to prevent disruption, to keep invading Others — and change itself — at bay.

But here’s where things get sticky. While everything I said above about the disruptive effects of gentrifying neighborhoods is true, it’s also true of places most of us would consider success stories, inspiring examples of neighborhoods and communities that fought back from economic despair and social isolation. And it is also true that within those success narratives are individual stories of frustration and disappointment. Even failure. Change happens. Every place is forever becoming a different place.

The gentrification subject, like so many that inspire arguments over how we’re to live with one another, is layered with contradictions and complexities. It deserves one of those rational conversations we have a hard time scheduling. But we should at least resist ratchetting up the fear and anger by pretending gentrification means only one thing, displacing vulnerable folks in order to accommodate the well-off.

We’ve taken on this topic before, here for instance. And Lance Freeman, writing for the Washington Post, summarizes “The Five Myths of Gentrification” here. But the most exhaustive and accessible analyses of the yen and yang of the subject are coming from Joe Cortright and his contributors at City Observatory. Download their report, “Lost in Place: Why the Persistence and Spread of Poverty – Not Gentrification – Is Our Greatest Urban Challenge,” here.

What’s most troubling about our persistence in the fear and resentment mode is its tendency to inspire the opposite of what we say we want. Fighting an influx of people and investment in the name of neighborhood protection denies neighborhoods resources they need to cope with change. Throwing up barriers to a broad range of development in neighborhoods closest to jobs, transit and shopping in the face of growing demand for living and working in those places only widens the supply-demand gap. Which raises the price for enjoying those amenities beyond the means of any but a monoculture of high wealth.

The more we infect a community dialog with fear and resentment the further the contagion spreads through all incomes and ages. When it reaches those whose choices are most restricted, there’s trouble in the streets. When we encourage fear in those with the resources to insulate themselves from threats, the more protective they feel about their privilege and the less invested they are in the neighborhoods, schools and other institutions that sustain the rest of us.

We should maybe talk about this without all the shouting.

–Ben Brown

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.