A Placemaking Journal

The Next Frontier for Compact Walkability? It’s gotta be the burbs

This weekend in Miami, the Congress for the New Urbanism is staging one of the periodic Councils it uses to focus perspectives and best practices on topics of growing concern to CNU members and fellow travelers. This one is all about building “a Better Burb.”

The idea, says CNU CEO Lynn Richards, is “to leverage the momentum from the revival of the city.”

Local and regional governments in outlying areas, says Richards, are beginning to recognize the advantages of reversing sprawl — and the risks of not acting. “And they’re asking for tools and strategies to start or accelerate their suburban transformation. That’s what we’ll be focusing on this weekend.”

Crossing the Urban/Suburban Divide

To those who haven’t been following this sub-movement within and parallel to the New Urbanism movement, suburban rescue might seem like mission creep. New Urbanists, after all, are best known as champions of urban life and of design and planning approaches likely to enhance it.

Historic downtowns and close-in neighborhoods — the places that assured compact, walkable, mixed-use livability before car-dependency took over — those are the places worth supporting and emulating, right? Out in drive-till-you-qualify suburbia, where modules for living, working, shopping and just meeting up with friends are segregated by income and land use and accessed almost exclusively by automobiles — that’s a wasteland.

A characterization that stark is unfair. At least a little. While it’s not tough to find folks willing to go full snark on a half century of suburban wrongheadedness, there has always been a core group of urban-focused professionals fretting about where sprawl might be headed and how its impacts might be mitigated to enhance community and connectedness. When CNU was born, The Charter for the New Urbanism included the commitment to fixing sprawl among the organization’s core principles:

We stand for the restoration of existing urban centers and towns within coherent metropolitan regions, the reconfiguration of sprawling suburbs into communities of real neighborhoods and diverse districts, the conservation of natural environments, and the preservation of our built legacy.

Before even that, other design, planning and building practitioners spotted the challenge. While those prescriptions might fail to fully address issues we better understand five decades later, the effort deserves credit for identifying a potential crisis and its likely components so early in the era of American suburbia.

By the time Andres Duany, Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk and Jeff Speck published Suburban Nation: The Rise of Sprawl and the Decline of the American Dream in 2000, the suburban critique was in high gear. Then, a decade later came the beginning of New Urbanists’ how-to guides for fixing things: Sprawl Repair Manual, from Galina Tachieva; and Retrofitting Suburbia: Urban Design Solutions for Redesigning Suburbs, from Ellen Dunham-Jones and June Williamson.

Authors of both of the latter two books will be at the Miami Council. For a deeper exploration of the territory, see PlaceMaker Hazel Borys’s Q&A with Ellen Dunham-Jones here. And the CNU website has a whole section on its sprawl retrofit efforts.

A Rising Sense of Urgency

What is increasingly evident now is a need to pick up the pace of transformation. The hurry-up is inspired by what’s been happening over the last few years in cities — the “revival” Lynn Richards’ references above.

While there might have been an argument a decade back over whether or not a preference for city life among the two largest generations in history — the Baby Boomers and the Millennials — was real and lasting, that argument is pretty much over. Which is why Rob Steuteville can be confident of assertions like those he makes in a recent Public Square piece about the “10 Reasons for a New American Dream”:

This dream, adopted by growing numbers of Americans, is more about great streets than highways. It’s about freedom of choice in getting around. In this dream, what you are connected to is more important than who you are separated from.

So complete — and so rapid — has been what Alan Enrenhalt calls “The Great Inversion,” in which the burbs and cities have switched roles in the migration of the affluent, that there’s a whole new set of challenges for those who live, work and set policy in both urban and suburban areas.

What dominates conversations in cities now are concerns about affordability and gentrification. The suburbs, meanwhile, are struggling with growing levels of poverty and budget-busting demands for services and infrastructure support — the sorts of issues suburbanites might have thought they left behind in the city.

The Good News/Bad News of Overflow Demand

Given the current strains — social, political, economic — on both the cities and the burbs, you can build a pretty good case for pessimism. Especially with the current policy paralysis in Washington and in state capitals. But there’s a potential upside to the pressure, provided the spillover effect of unsatisfied urban demand helps drive the transformation of suburban sprawl. Consider:

It’s now clear that the time and resources necessary to ramp up urban housing supply and infrastructure is going to lag behind increasing demand for city life for the forcible future. So the affordability gap in infill locations where there are jobs and walkable access to daily needs is only going to widen. That’s bound to push people priced out of the most convenient and appealing urban neighborhoods into places that will come under pressure to become more convenient and appealing, to increase the supply of the high-demand amenities of compact, mixed-use walkability and bikeability.

Here’s the University of Arizona’s Arthur C. Nelson, whose research demonstrated the widening gap between what suburban-style housing stock supplies and what urban-oriented home owners and renters demand, talking about the new frontier for compact walkability in his latest book:

. . (I)mportant opportunities exist to redevelop America’s extensive networks of commercial corridors and suburban centers. I estimate that America has about twelve thousand square miles of land, an area equivalent to the states of Connecticut and New Jersey, that are used for surface parking, loading, storage, and other nonstructural uses. The supply of this land is so vast that nearly all of America’s new nonresidential spaces and nearly all new multilevel attached residential units can easily occur on the parking lots of existing nonresidential development, especially along commercial corridors and in suburban centers.

An Urban Amenity Transfer?

For business and political leaders in those suburban “receiving areas,” the best strategies will be about making the burbs better. Which means behaving more like compact urban places, with infrastructure and regulatory processes to match.

It’s not just the CNU and NU practitioners looking in this direction. The Urban Land Institute, which was among the partners on that 1959 video above, is making a strong pitch for such strategies. In 2012, the ULI’s Infrastructure Institute released a report, “Shifting Suburbs: Reinventing Infrastructure for Compact Development,” which made the case for bringing the tools of urban-style redevelopment to the burbs:

The signs point to continued change—and a continued need for innovation—in the suburbs. . . As American suburbs build in more compact ways—with higher-density development clustered in nodes or along corridors and with increasing options for getting around without a car—reworking or rethinking infrastructure can be essential. For compact development to occur, developers and municipalities must determine how to plan, fund, and finance the often costly and complicated infrastructure required for suburban compact growth. That infrastructure can include transit investments, structured parking, intricate street grids, sidewalks, streetlighting, and water, sewer, and other utility upgrades.

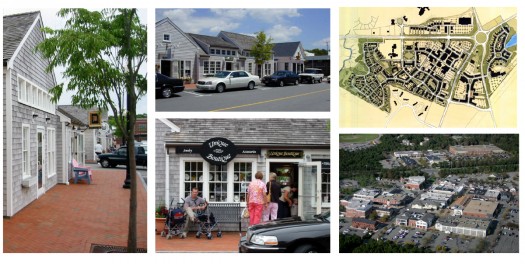

There are already scattered examples of suburban retrofits. There are megaprojects like Tysons in Northern Virginia, which is so ambitious, costly and fraught with political and logistic hassles that it’s probably not the ideal model. At this week’s Miami Council, attendees will take a look at examples from Mashpee Commons in Massachusetts.

An early retrofit of an outmoded suburban mall, Mashpee Commons began its transformation, with DPZ & Co. as design lead, in the late 1980s. It has evolved into a mixed-use core for an emerging town where once there was centerless suburbia.

“We have learned lots of lessons over the years,” says Tachieva, “in the redevelopment of urban neighborhoods, in the creation of town centers, in the sorts of regulatory and physical infrastructure necessary to deliver what citizens and municipal leaders want.

“We are all doing work in what are already walkable suburbs,” she says. “But we want to concentrate efforts in places that need the most help. So we need to sharpen the message a bit and become more focused.”

That amounts to an overview of this weekend’s agenda in Miami.

The Councils are organized to not only talk through issues and approaches but to propose new strategies and tools. Watch for those ideas to circulate among practitioners — and maybe in a burb near you.

–Ben Brown

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.