A Placemaking Journal

Making Better Places to Fail: Take those jobs and . . (Part II)

First, let’s review:

Of all the sub-topics in urban planning and design, the ones likely to generate the most anxiety are those where land use planning intersects with economic development. Old-school economic developers signal their nervousness pretty quickly when they sense planning strategies are heading in directions that might keep them from promising infrastructure goodies or regulatory exemptions to firms they’re wooing.

No parking in front or drive-through capacities? Zoning that pulls buildings up to the street? Well, there goes business investment in our community. And you know what that means: Fewer JOBS for our people.

Pelted with those arguments for years, Smart Growth wonks decided to meet the opposition on its own turf and did the math. In studies like this recent one from Smart Growth America and in the work of return-on-investment advocates like Joe Minicozzi and Chuck Marohn, evidence suggests that not only do walkable, mixed-use urban areas not inhibit economic growth, they enhance it. In fact, investing in the infrastructure and policies that provide less walkable urbanity and more sprawl is likely to cost more and deliver less.

That understanding is now close to conventional wisdom for private sector leaders planning for the post-industrial area. Take for instance, the shift in strategies for redeveloping North Carolina’s Research Development Triangle Park (RTP), where thinking has migrated from an emphasis on a suburban-style office park environment to one more like an urban, mixed-use neighborhood.

“The switch from recruiting big companies . . to smaller companies, more entrepreneur-based companies, I think that is the future of job growth,” RTF board member Dick Daugherty told the Triangle Business Journal for an early October story.

“The open spaces — from the stream park to the art spaces — as well as the coffee shops create places for people to connect,” said Smedes York, chairman of York Properties and RTF board member, in the same piece. “It makes the Research Triangle Park a community.” Adding residential blocks to the Park, said York, “is key.”

You know, sort of like what you get in a city.

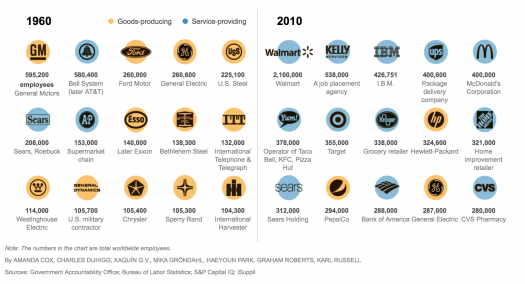

The tectonic shift forcing this rethinking has been in the works for decades. Take a look at this New York Times graphic from a couple years back:

What we see here is a half-century of evolution from a U.S. economy dominated by manufacturing to one in which the service sector employs most folks and accounts for the most aggregate output.

That doesn’t mean manufacturing is dead in America. There are still good jobs in goods-producing businesses. Some pay even better than manufacturing jobs in the glory days of the industrial area. There are just a lot fewer of them, thanks to globalization and the accelerating impacts of robotic technology and other productivity game-changers.

Those who keep track of the numbers see no major changes in the trend. In its 2013 projections for the next decade, the Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates the share the goods-producing sector claims of the country’s “nominal output” will decline a little less than one percentage point from the 25.4 percent it accounted for in 2012. The service sector, on the other hand, is expected to grow its share a percentage point to 69.4 percent of the U.S. economy by 2022.

This gets us to where we left off in a late August post. The argument there was about the extent to which growth planning should depend on chasing “job creators” when the jobs we’re talking about are not only less in number, but also less stable than the ones that helped create the middle class in the industrial era. According to the Small Business Administration (), about a third of start-ups are no longer around after only two years. Only about half are able to survive at least five years.

In the quick-to-market, quick-to-flop culture of Silicon Valley, failure is often framed as a teaching moment, a chance to regroup for another run at venture capital and another start-up. Elected leaders at every level who feel obligated to promise “quality jobs” for all and economies rescued from service sector instabilities can be forgiven for not embracing “fail fast, fail early, fail often” enthusiasms. At some point, however, we’re all going to have to find ways to indemnify ourselves and our communities against the worst effects of this volatility.

How ‘bout this for a suggestion:

Let’s stop thinking of community livability and equitable opportunities as conditioned on cobbling together a 21st century-style economy that was already on its way out in the latter part of the 20th century. And let’s stop giving old-school business groups and economic developers veto power over urban planning strategies likely to provide way more resilient environments for an era in which economic uncertainty is anything but uncertain.

Fortunately what Smart Growth and New Urbanist planners and designers already know — and what new era entrepreneurial types like those reworking the physical environment of the RTP are putting into practice — goes a long way toward making better places to tolerate failed enterprises.

The push in most communities is to use some combination of subsidies, incentives and regulatory bullying to muscle businesses into picking up most of the tab for closing community livability gaps. Why not attack problems more directly by using available tools of government — particularly land use and transportation planning — to make it easier for citizens to survive low-wage economies and, not incidentally, to better position them to be around to help invent whatever comes next?

Planning that delivers the broadest possible choices and scales of places to live, do business and get around without relying exclusively on private automobiles is the kind of planning that stretches family budgets. We know that. But it’s only part of the story. The best research and the most successful entrepreneurs in this new era suggest that despite the propensity for serial failure baked into the start-up culture, environments that allow for continuous, casual connectivity between people and ideas are precisely the ones most likely to nurture firms that survive and thrive and employ lots of people.

Bottom line: Given what we know about work and workplaces in the new era, maybe making better places to fail is a more noble urban planning aspiration than settling for less by framing wishful thinking as chasing success.

–Ben Brown

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.