A Placemaking Journal

The Unkickable Can: Towards a ‘Livability Synthesis’

Maybe it’s a brief glimpse, inspired by Pope Francis’s visit, of a collective will to be better humans. Or maybe it’s just the math. But I’m feeling more hopeful about future traction for arguments — and for action — for more meaningfully connected, livable communities.

The reason why can be summed up in two charts:

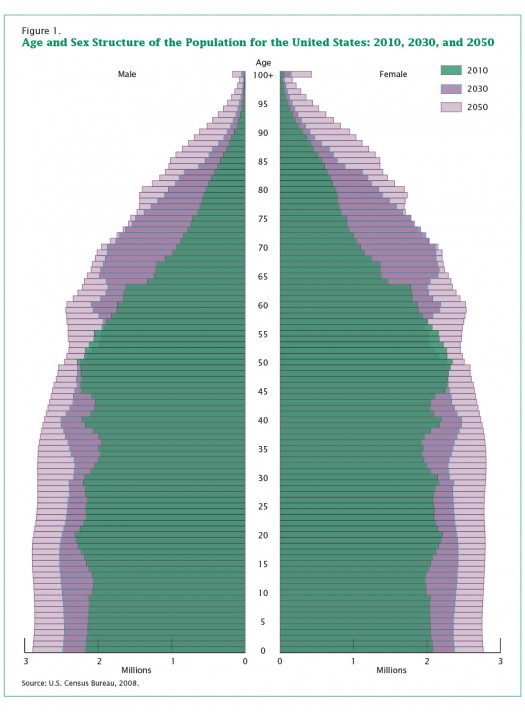

The first chart is the now-familiar elongation of population modeling as Baby Boomers, born between 1946 and 1964, move into the final stages of their lives. We used to characterize the generational swell Boomers created as a “pig in the python.” These days, with the even bigger generation of Millennials, born after 1980, coming of age, the snake looks more proportional. Still, the sheer size of the Boomer generation enables it to prolong its capacity to bend trend lines over the next forty years.

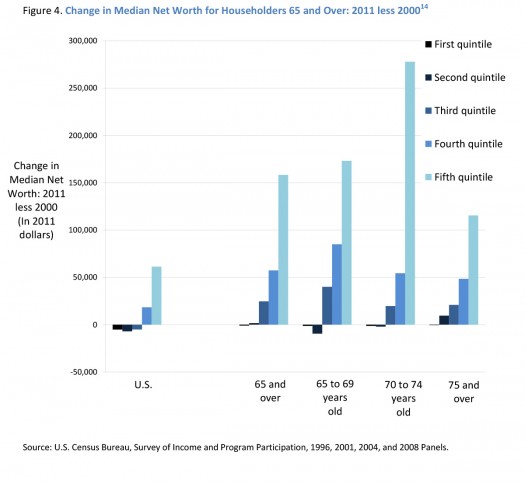

That capacity is multiplied by what the second chart makes obvious. Geezers have most of the money. Which in the pay-to-play society we’ve evolved over the last four decades, means older people — who vote more consistently, contribute more to political campaigns and have more highly developed networks of influence in business and non-profit institutions — are likely to have more clout in decision-making that touches the lives of citizens of all ages and at all income levels.

Let’s go out on a limb here and suggest that rich people’s disproportionate power has not always been a wonderful thing for the rest of us. They’ve been able to cherry-pick issues and programs that benefit their exclusive interests and use their political and economic leverage to protect and enhance their privilege.

What’s likely to change as the wealthy grow older is that a lot of what will inspire their investments of resources and influence is no longer so exclusive. Mortality disciplines priorities.

While it’s true that older people of substantial means can afford entirely privatized networks of support and care as they become more frail, every extra dollar they spend creating and sustaining those kinds of networks is money subtracted from what insulates their families from the inconveniences that frustrate the majority of Americans. Many will opt for doing what they’ve always done to influence policies, particularly government policies, that deliver services they want at the substantial discount that broad public investment provides.

It’s tough for a lot of us to see the rich as interested in something that will also help those far less affluent. We’re distracted by the gaudy expenditures of the 1 percent — or the 1/10 of 1 percent — who distance themselves from everyday annoyances with toys and minions. But look at the chart above again. It’s really the top wealth quintile, those claiming the highest 20 percent of U.S household affluence, that accounts for most of the influence-wielding. And many of those folks are already putting their money where the interests of communities and residents intersect with their own.

Take, for instance, the back-to-the-city movement of the affluent Boomers. That migration complicates all sorts of things for communities worried over gentrification and community affordability. Wealthier households and more educated citizens attract more private sector investment; but they also bid up the prices for housing and services and threaten the character of existing neighborhoods.

As we’ve pointed out before — here, for instance — those are the challenges of success. Which make them infinitely preferable to the kinds of problems confronting places where no one wants to live or invest money. The challenges of success are about leveraging demand to capture value, then managing the allocation of benefits equitably.

Cynical politicians push the “trickle-down effect” of wealth as if it were an inevitable, natural law, like gravity. But wealth sharing requires heavy lifting on the part of policy-makers and policy-enforcers — which, by definition, means countering the gravitational forces that tend to concentrate both wealth and poverty. It’s work for strategic planners and committed policy-makers. And it’s been tough going for many communities and their leaders.

I’m arguing that the politics could get easier, thanks to the emerging common ground and the sense of urgency inspired by so many aging citizens. Faced with other humongous challenges, whether it’s social and economic inequities or climate change, we tend to invent reasons to postpone action, to kick the can down the road. But the impacts on families and communities of the aging of the largest generation in world history add up to an unkickable can.

Every day, 10,000 more Americans turn 65. Unless lives are cut short prematurely by accident, they — we — are on journeys marked by progressive stages of vulnerability. Our denials of that reality are going to be reduced to irrelevance not just by the statistical evidence, but also by the experience of watching friends and family members struggle with the passage regardless of their incomes or political affiliations.

Death is the only inevitability shared by every living being. Which means everybody has a stake in policies and programs that improve the chances of negotiating life’s final stages with as much support and with as little hardship as possible.

What would those policies and programs look like?

Start with improvements in our patchwork healthcare systems, right? In Medicare, the elderly have enjoyed access to a comprehensive health care program that, combined with Social Security, has rescued several generations from poverty in old age. But Medicare doesn’t cover dental or hearing needs. Nor does it pay for the most costly medical expense seniors may need — long-term care. Most people in skilled nursing facilities have exhausted their own assets and rely on taxpayer-funded Medicaid to retain access to long-term care.

More folks aging. More of them living longer and into stages where costs of care escalate. More pressure on family and government budgets at every level. Want to bet whether that suggests a new sense of urgency or a growing constituency for new solutions?

The most logical, cost-effective solutions have to do with prolonging stages of healthy independence to avoid or arrest disabling chronic disease or the need for 24-hour skilled nursing. Which gets us back to the common ground shared by the affluent and the rest of us.

Communities can play a pivotal role in achieving this goal by making healthy choices easier and making changes to policies, systems, and environments that help Americans of all ages take charge of their health.

That’s from the 2013 Centers for Disease Control publication, “The State of Aging Health in America.” The CDC, AARP and other agencies and organizations have become fierce advocates of approaches long championed by New Urbanists and Smart Growth advocates:

Compact, walkable, transit-served mixed-use communities. You know, the kind of places so many of the affluent Boomers are paying a premium for.

Our resentment of the wealthy, hardened during the recession, may have kept us from recognizing the opportunities their investments in walkable urbanity imply. But soon, more folks are likely to help break through the sorting of political constituencies into sub-sections of special interests and see ways in which goals are not only connected, but interdependent.

Take a look again at the first graphic above. Notice how women begin to outnumber men in the growing 85-plus age group? Many of those women live by themselves, isolated from services and social relationships that could help them maintain their health and their finances into their later years. So ending isolation and accessing the social and economic amenities that more complete communities provide are women’s issues, no?

Racial and ethnic minorities have less household wealth than non-Hispanic white households. So they’re severely disadvantaged when it comes to buying their ways into a system that eases strains on their families as they age. Which means healthy aging is an issue for black and Hispanic voters.

Younger people will struggle less to launch careers and start families if they can get the help other generations have enjoyed if their parents don’t have to deplete their savings to pay for end-of-life care. So these are issues that connect young and old.

Political liberals want change that brings fairness to the ways we allocate support for those who need it most. Political conservatives want bang for the buck.

The potential effect of these merging interests could be, as Scott Bernstein characterizes it, “a synthesis for livability.”

Still heavy lifting ahead, without doubt. Yet the alignment of so many forces and interests — and the power of demographic inevitability — could lighten the load considerably.

–Ben Brown

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.