A Placemaking Journal

Kimmirut: Heart of the Arctic Day 6

Wednesday, July 22, 2015

Kimmirut is a community of about 500 people, with the buildings clinging precipitously to the sloping landscape. The day was surprisingly warm, with a high of 14 C and sunny skies. Children were lining the shore to greet us, and their inquisitive brightness was the highlight of the day. We were the one and only passenger ship into the village this year, and almost every villager came out to spend the afternoon with us. Some of the stories the children told me were rather tough, and it clearly isn’t easy making a life here.

The village tour included the school, Soper Gallery, the Arctic College, the two stores, church, and cemetery. An elder shared some of their town history along with a demonstration of seal preparation. A drum dance and Inuit competitive games were interrupted by an Elvis impersonator and spontaneous dance party.

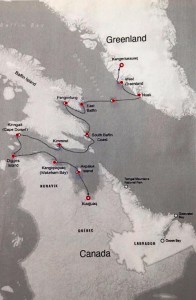

To get to Kimmirut, we travelled up the Soper River, named after naturalist Dewey Soper (1893-1982), who helped lead the Eastern Arctic Patrol in 1923 and set up Royal Canadian Mounted Police stations. He later found the illusive Blue Goose nesting grounds, and was known for the rest of his life as Blue Goose Soper.

Our wakeup call this morning wasn’t about polar bears, but to draw our attention to sizeable icebergs in view. All of the icebergs we’re seeing on this expedition were courtesy of Greenland. We kept a keen eye on them, since an iceberg from Greenland is what sunk the Titanic. The above-water portion of the iceberg may be as little as 10% of the total mass, hence the old adage, “the tip of the iceberg.” Icebergs are different than sea ice — icebergs form when glaciers calve, and are easy to differentiate from the more horizontal, low-profile sea ice. The icebergs we’re observing are thanks to the Greenland Ice Cap, which covers 95% of the island, is up to 2 miles thick, and centuries old.

Much of today’s landscape is made up of marble, a metamorphic rock that started its life as limestone. The great island just in front of the town of Kimmirut is marble as well as a mineral called corundum, made up of aluminum and oxygen. When corundum is blue, it is sapphires, when it’s red, it is ruby, and green corundum is emerald.

We spotted three species of seals today. The ringed seal is the smallest seal, and important to the Inuit for food and clothing. These seals can dig a hole under the pressure ridges of ice to create a domed ice cave to have their beautiful white babies. We also saw a bearded seal, the biggest of the seals of the Arctic. The harp seals we encountered are so called because of the black harp-like design on their backs, set off nicely against gorgeous white faces.

The landscape here is striking. When tide is high, there is a waterfall from the river into the lake. When tide is low, the waterfall is out of the lake.

Today started a workshop series on board regarding stone carving, fish printing, language lessons, bead work, and photo workshops. Also one group discussed our Inuit Art Center in the works at the Winnipeg Art Gallery (WAG). The biggest challenge is answering, “What is an Inuit art center?”

Just like the iceberg, so much of the Inuit Art Collection of the WAG is below the surface in the vaults of the museum, and this project is about bringing it to light. The WAG’s 14,000 Inuit art objects span over 60 years and represent the key moments of contemporary Inuit art. The museum has an unprecedented record of 160 exhibitions, supported by more than 60 catalogues and books.

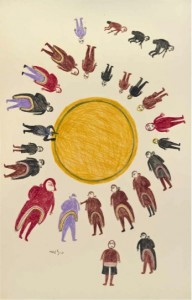

The wonderful sense of order, freedom, and equality of place that summed up in the print, The Drum Dance, are essential for the new Inuit Art Center. To help with that, many Inuit leaders are guiding the new center, by serving on the WAG board of directors, curatorial staff, and advisory committees.

For the building itself, the international call for proposals was answered by 63 submissions from 13 countries. The reason architect Michael Maltzan was selected was because of the questions he was asking as much as the answers he was proposing. The schematic design is informed by many trips to the Arctic, and underlines the ideas of the figurative landscape, the sameness of scale, and the sense of limitlessness here.

As the midnight sunset approached, we called it a night, grateful for the calm waters and much food for thought.

To read the entire Heart of the Arctic series, go here.

–Hazel Borys

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.