A Placemaking Journal

Aktopak: Heart of the Arctic Day 2

Saturday, July 18, 2015

In the Arctic, summer sunrise comes more or less immediately after sunset, but thanks to the ship’s portholes and calm waters, we slept through. At 6:45 a.m., a happy voice over the sound system awoke us earlier than expected, calling out four polar bears on the beach of Aktopak Island, just starboard of where we had anchored. Sleepy passengers gathered on the 8th deck, talking in hushed excitement.

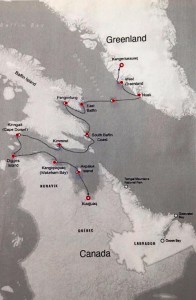

Aktopak is an impressive fortress of an island, with shear cliffs up to 244 metres high. This 480-million year old limestone is heavily jointed due to tectonic shifts and compression. Our expedition will experience about 2 billion years of earth’s history, like this island that was formed in the southern hemisphere millions of years ago, then thanks to continental drift relocated in the north.

Being accessible only by air, it’s the nesting grounds of about 2 million thick-billed murres, the largest colony in Canada. These birds lay conical shaped eggs on the tops of the formidable cliffs, so that they roll in circles and are less likely to fall off. When it’s time for the young to fledge, they cannot yet fly. The parents push them off the ledge, where the air currents guide them to the water. Their fathers swim with them to the Atlantic, by which time they are strong enough to fly.

While the polar bear population in the Western Arctic has suffered from global warming, the numbers in the east are stronger. We had the pleasure of sighting ten today, including two mothers with cubs. Thanks in large part to all the murres.

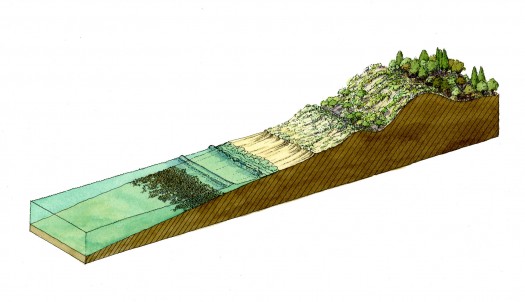

The inhabitants fitted so closely to their habitats were a forcible reminder of the Transect. Ecologists have long used this idea to identify and study the different plants and animals that thrive in various places. For the last 35 years, urbanists have co-opted the Transect tool to study the rural-to-urban landscape, and the various people and economies that abound in different places along the spectrum. “A place for everything, and everything in its place.” Just as you wouldn’t wear a tuxedo to a square dance, the bears are unlikely to be on the 700’ cliffs. But the murres thrive here.

We saw a male who was likely around 12 years old, weighing in at about 700 pounds. Next up was a mom with two 75 to 90 pound cubs. And another mom with one cub. All three cubs were just born, and will remain with their moms for two years. Going to Akpatok Island and looking for bears is like going to NYC and looking for a yellow cab. If you can get there, you can find one.

It’s the getting here that can be tricky. We were fortunate to have this great day for birds and bears. Just Tuesday, there were 3 to 4 metre seas on Hudson’s Straight. And today was calm, allowing us to explore in zodiacs. Two weeks ago, this water was solid ice, and we would not have been able to navigate. When the ice melts, massive nutrients are released, and life flourishes. The bears come here for their summer holidays, to hang out on the beach, and dine on the murres that are less lucky in fledging or the stray egg.

We saw the mom with one cub ambling down the beach to come face to face with the 700-pound male, and a very interesting dynamic played out. The male was full from the winter of seals and definitely didn’t want to tangle with the proverbial and literal mother bear, so took to the water. He swam by them, and only came ashore when he was out of swatting distance.

Not only did we see thousands of murres, and ten polar bears, but we also saw the illusive Sabine’s Gull. A rare treat, so long as you aren’t too close to this aggressive bird.

Extreme temperature ranges of 120 F, from -60 to +60 F, are made livable by a wide variety of adaptations in Arctic wildlife. Polar bears survive with countercurrent blood flow keeping warmer blood deep and colder blood nearer the surface, the ability to go 9 months with very little food, hair that is hollow for air insulation, and black skin to absorb heat. Two layers of fur — guard hairs and underfur — act like a rain coat over a down coat.

The Arctic is the last great wild place on earth. Just as its formidable land patterns and weather make survival challenging, they also teach countless lessons in resilience.

Photo credits for last three images: Mark Seth Lender.

To read the entire Heart of the Arctic series, go here.

–Hazel Borys

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.