A Placemaking Journal

Ideas Converging for Housing Opportunity: Some sorta oldish, lots very NUish

When we look back on this period, we might discover that the effort to ramp up realistic approaches to the challenges of community affordability reached some sort of tipping point in the spring and summer of 2015.

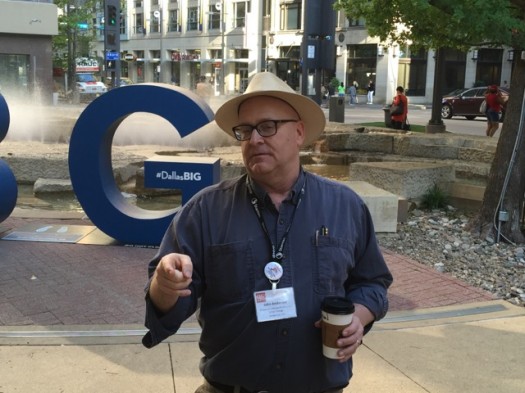

It surely had something to do with the passion and impatience on display in Dallas when the Congress for the New Urbanism held its 23rd annual gathering, April 29-May 2.

Passion is not hard to come by at these events, since we can rile one another up over just about anything. (Full disclosure: I’m a CNU member, and PlaceMakers partners have from time to time worked directly for the organization.) But what distinguishes this sub-group of designers, planners and engineers from theorists in the same professions is our extreme weakness for strategies that work, that contribute to the goals of building better places for more people in some time frame short of forever.

We have a Charter that lays out the proven components of better places at scales from the parcel to the region. It’s a get-‘er-done manifesto. Hence the impatience when new urbanists sense foot-dragging on action steps — like the ones necessary to broaden the range of housing options to achieve equitable community goals.

Rob Steuteville, longtime chronicler of all things new urbanist, now writes his formerly independent “Better Cities and Towns” report as a new CNU staffer. He chose as one of his first blog posts under the new arrangement an update on R. John Anderson’s mission to create a cadre of developers of small-scale projects in just about every urban area:

For the big developer, 200 units may be the minimum to pay for all of the specialists. For the small developer, any number may make sense for building a portfolio with sound, long-term investments. New urbanists bring a certain skill set to infill development: ‘They have a very good idea of the missing teeth in a neighborhood,’ Anderson says. ‘If you provide the missing teeth, your neighborhood is now a perfect smile and the units will be worth more than the ones on the highway.’

Anderson came into the Dallas meetings with a small but dedicated core of developer wannabes and left with something like 160 people asking to be included in a Facebook group called “Small Developers/Builders.” By yesterday, the Facebook group had already expanded to 300-plus members. By the end of the year, when Anderson and colleagues have appeared at as many of the requested Rookie Developer Workshops as they can manage, the effort will have assumed a momentum all its own.

Credit John Anderson’s droll humor and straightforward framing of the challenge for a lot of this excitement. “I used to get pretty worked up about every lousy building that crossed my path,” he says. “Since the supply of lousy buildings seems to be inexhaustible, and my time on earth is limited, the practical thing to do is for me to stop caring about lousy buildings, regardless of style.”

Better, he says, to just build better places. “I think forcing those who would build crap to compete with better buildings is a more affirmative approach. . . I have found the results of this approach to be a big reduction in day to day stress, similar to canceling cable TV.”

What gives Anderson’s ambitions the advantage of an idea who’s time has come is its determined pragmatism. Which is what his strategies share with all the other reality-tested approaches of new urbanism. If building better places is the goal, then adapting strategies to do that is the sorting mechanism.

The goal has never seemed much of an issue. There are plenty of examples of what makes some places a lot better than other places for being safe, for moving around without exclusive reliance on automobiles, for working and shopping. For being young or growing old. For being healthy and happy. So let’s just build more of those places.

The problem, of course, is that in the delirium in the aftermath of WWII we created this hairball of obstructions from the unintended consequences of auto-dependent, zoning-enabled, Ponzi Schemed suburban sprawl. Regulatory policy, construction and mortgage finance, infrastructure investment and a bunch of other not-so-obvious additives knotted the hairball. New urbanists and those they influenced have been working at unraveling it for the better part of four decades. In John Anderson’s pragmatism, you get a glimpse of how all the elements that come into play, almost all of them derived from new urbanist/smart growth adaptations to reality.

Thinking in smallish increments is the workaround strategy required in the face of realities of finance and regulatory policy. Really big stuff takes lots of time, money and brain damage — to say nothing of the opportunity to make mistakes that might take generations to fix. Think Urban Renewal.

The recent financial unpleasantness provided a reality check. And new urbanists were among the first to identify adaptive approaches. Take, for instance, Victor Dover’s observation back in 2011 about the necessity for thoughtful “incrementalism”:

Get-‘er-done determination, inspired in part by the planning and building paralysis of the Great Recession, helped spawn new urbanist sub-movements like Tactical Urbanism and more recently, Lean Urbanism. Efforts like those prepared the way for Anderson and his cohorts to make their case.

Going back even farther, a direct path for the Rookie Developer adventure was charted in the CNU-directed Mississippi Renewal Forum after Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Anderson was on the Forum’s architecture committee that developed a series of plans for Katrina Cottages — small-scale houses that could serve as temporary disaster relief shelters, then transition to permanent components of infill neighborhoods.

With the 10th anniversary of the hurricane approaching this summer, decade-later recaps of what worked and what didn’t will revisit the Katrina Cottage story. Center stage will be the work of Bruce Tolar, an Ocean Springs, Mississippi architect and also a member of the 2005 Forum architecture team.

Tolar took the cottage idea the next step, creating a model infill neighborhood of Katrina Cottages, then partnering with a regional non-profit and a private developer to build two other single-family rental neighborhoods based on the model. More are in the works, and Tolar’s in demand for coaching others how to do similar projects. We’ve followed Tolar’s work regularly, connecting it to the larger themes of affordability, most recently here.

So here’s the point. John Anderson, Bruce Tolar and all the rest of the independent innovators are happily leveraging all this impatience-driven work by others to advance the cause of getting some really good components of really good places built as efficiently as possible. That makes them among the latest in a list of tip-of-the-spear practitioners combining their own experience and expertise with the lessons of others who share similar commitments to the easy-to-grasp, hard-to-realize ideas driving new urbanism.

Go forth and multiply, I say.

–Ben Brown

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.