A Placemaking Journal

Here’s to Zimmerman/Volk and to ‘Attainable Housing’

I should maybe feel at least a little guilty for escaping the cold weather in the North Carolina mountains where I live and heading to Florida over the weekend. But I don’t.

The destination was, after all, Panhandle Florida, the vertically challenged part of Florida that folks farther south call “LA,” as in “Lower Alabama.” Which means I was still wearing a down jacket when I ducked outside.

Also the trip was for a good cause. The occasion was the annual Seaside Prize Weekend, sponsored by the Seaside Institute.

The Seaside Prize goes to “individuals or organizations that have made significant contributions to the quality and character of communities.” Obvious candidates are from the fields of design and planning. But receiving the award this year was a team of residential real estate analysts, Todd Zimmerman and Laurie Volk.

Since the late 1980s, ZVA, as their firm is called, has helped developers overcome the tendency of supply-demand market research to predict the future by looking at the past. Zimmerman and Volk project potential market opportunities by more closely examining behavioral characteristics of demographic slices, especially the biggest slices of all — Baby Boomers and Millennials.

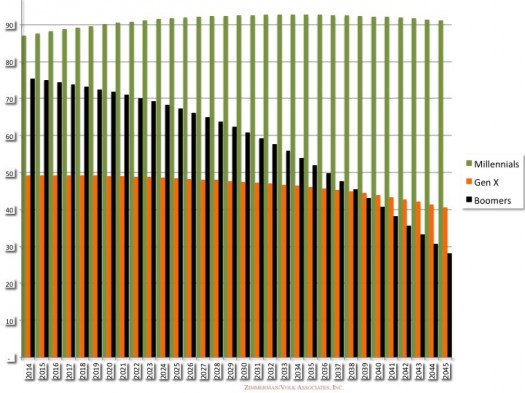

Years before demography became a thing for many of us, ZVA was using some version of the graphic below to hammer home the inescapable impact of 150 million-plus people in these two generations — the Boomers, now aged between 51 and 69, and the Millennials, who, in 2015, are between 19 and 38.

Even a relatively small percentage of either of those generations could move the demand dial significantly. When their preferences overlap, the effect could be game changing, especially if their preferences were being under-recognized and underserved in the current marketplace. Which is exactly what Zimmerman and Volk spotted in the two generations’ similar longings for urban connectivity in a housing market delivering mostly suburban isolation. The credibility of their research, combined with their fierce advocacy for what it implied, assured them a crucial role in the advancement of New Urbanist ideas and projects.

At Seaside over the weekend, Zimmerman and Volk led a slightly deeper dive into Boomer/Millennial trends post-Great Recession and encouraged a broader conversation about “Neighborhood Challenges for a Re-Urbanizing Nation.” Mainly the dilemma linked to rising inequality and community unaffordability. The slides below offer an edited version of how they set the table.

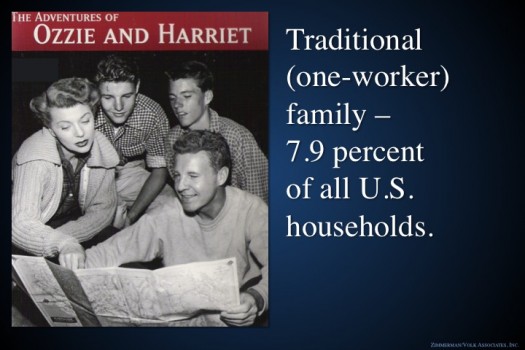

Of course, we’re not so resistant to reality that we still believe traditional family life in America implies a single-working spouse and a couple of rug rats. But not many of us grasp how little that resembles the current American household — or the current American homebuyers.

All of which suggests customers for the “traditional” American home are in the minority. Yet homes designed for the “traditional family” comprise the majority of choices.

New Urbanist designers and developers, often helped by ZVA’s analysis of an underserved potential market, have tried to address the misalignment. But many will admit that for a lot of reasons, including stuck-in-the-past zoning and financing systems, closing the gap is slow work. And it’s made even worse by a recession that exposed weaknesses in every component of housing policy and undermined illusions of wealth in significant segments of both mega-generations.

No one at the Seaside Prize weekend events missed that irony that we were wading into a discussion of “attainable housing” (which is substitute wording for “affordable housing” urged by Rhode Island developer and presenter Jan Brodie) while we were sitting in a New Urbanist community that now requires a buy-in north of $1 million. That part of the discussion, engaged earnestly over the weekend, deserves fuller treatment in other posts. But it’s worth making a couple points.

First, the absurdly high prices in Seaside and in other New Urbanist Traditional Neighborhood Developments aren’t because ZVA and others misread the demand for such places. Just the opposite. The value the market placed on even modestly sized homes in these neighborhoods can be attributed mostly to the success of some pretty good ideas about prioritizing design that enables community and connectivity. There’s just not enough of it.

Escalating demand, insufficient supply. Up go the price points. Basic economics.

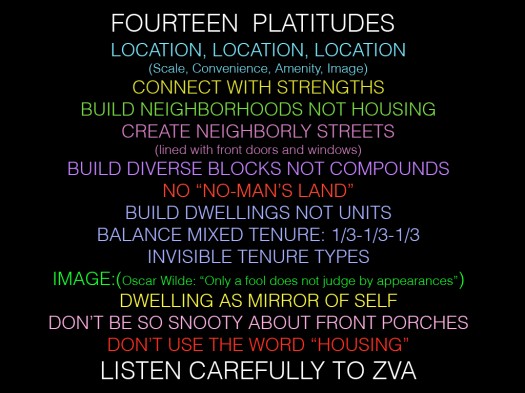

Whatever the answer to that problem, it can’t be about lowering the quality bar. One of my favorite other presentations was one by architect/planner Ray Gindroz, himself a former Seaside Prize recipient. Gindroz offered 14 “platitudes,” so familiar as to be clichés, yet essential to make the kinds of neighborhoods that New Urbanists claim to value. It’s a kind of a “keep the faith” reminder.

It’s important also to remember that because of the commitment of people like Seaside developer Robert Davis, places like Seaside can contribute to attainability solutions.

Here’s architect/planner Dhiru Thadani, another Seaside Prize winner, explaining how versions of the Katrina Cottages designed by New Urbanists after Hurricane Katrina in 2005 came to Seaside to model attainability:

–Ben Brown

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.