A Placemaking Journal

Small to Go Big in 2015?

Maybe. Finally. Here’s why.

Those of us who’ve been tangling with status quo protectors in housing design and policymaking got a charge out of Justin Shubow’s Forbes blog post earlier this month. Shubow backhanded modernist starchitects for persisting in their personal artistic vision without regard to the human use of real places:

“Modernism might appear outwardly impregnable: it dominates the practitioners, the critics, the media, and the schools. But as the example of the Soviet Union shows, even the strongest-appearing edifice can suddenly come crashing down when it turns out it no longer has internal support.”

Shubow was piling on to a similarly fierce critique by Steven Bingler and Martin Pedersen in a December 2014 op ed in the New York Times:

“We’ve taught generations of architects to speak out as artists, but we haven’t taught them how to listen. So when crisis has called upon our profession to step up — in New York, for example, post-9/11, and in New Orleans after Katrina — we have failed to give the public good reason to trust us. In China and in other parts of Asia, Western architects continue to perform their one-off magic, while at the same time repeating many of the urban design catastrophes of the previous century, at significantly larger scales.”

Both posts pointed to the misguided enthusiasm among modernist designarati for the Brad Pitt-backed “Make It Right” experiment with New Orleans replacement housing after Hurricane Katrina. “The predictable result,” says Shubow, “was weird, sometimes discomforting houses of non-native motley futuristic design that have virtually no relation to each other or the beloved historic architecture of the city.”

That was fun to read because so many of us were urging an entirely different approach after the 2005 Biloxi Mississippi Renewal Forum. That was the mega-charrette that, among other planning achievements, launched a Katrina Cottage movement for small-scale solutions to resilient neighborhood design. Shubow used the contrast between “Make It Right” and the Katrina Cottage effort to drive home his points about employing design for something other than a personal statement.

This urge to new thinking comes at the start of the year that will mark the 10th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina. Back in 2005, cottage and cottage neighborhood solutions seemed so obvious — and so immediately popular among those outside the modernist echo chamber — that it seemed just a matter of time before dozens of Katrina Cottage variations would be used to address a combination of issues related to sustainability, affordability and right-sized living in a new era. That it’s taken a lot longer than any of us imagined hasn’t diminished the likely role of small-scale housing and neighborhoods in the years to come. And the pace is picking up.

First of all, the economic and demographic forces we’ve talked about before — here and here, for instance — are even more apparent now. So barriers of finance, zoning and building codes built to enable conventional suburban development have to fall in the face of increasing demand.

It helps, too, that a significant portion of this expanding niche for small-scale livability is driven by market demand and not just affordable housing needs. Market-rate price points give designers, developers and builders the chance to overcome the training of 50 years of suburban house buying equating value to lowest cost per square foot. These days, it’s clear that many buyers who could afford a lot more house are choosing better designed and built living space in smaller packages.

In a previous post, I pointed out the top winner in the 2014 Professional Builder Design Awards went to a 13-unit cottage cluster in Massachusetts on 3.7 acres with homes in the 1,340-1,760 sq. ft. range priced from $599,000 to $699,000. Serenbe, the popular New Urbanist community south of Atlanta, has started a waiting list for a 16-cottage cluster facing a green and sharing a common house. Price points: $425,000 to $475,000.

My favorite demonstration of high performance for small living spaces in high-end contexts is Seaside’s Academic Village. Northwest Florida’s Seaside community remains the most photographed example of early New Urbanist neighborhood design — and, not incidentally, for commanding high prices for small spaces. Take a look at this new addition to Seaside:

Now look at this scene of cottages, inspired by Katrina Cottage designs and manufactured through a special FEMA program in the wake of the 2005 storm, being installed in Cottage Square in Ocean Springs, MS:

And now this one:

Yep, all the same basic units. All manufactured with the FEMA appropriation.

The shot just above is of the same cottages as in the second photo, only with about three years of landscaping growth to nestle into. The Seaside shot is the most recent.

The Seaside Institute acquired 11 of the Mississippi units and customized them for the Academic Village — not, by the way, without consternation from some Seaside homeowners worried about “trailers” undercutting property values. Concerns dissipated as soon as it became apparent that thoughtful design made the units a pleasing addition to the community. A source of pride even.

So there you have one of the big lessons of the cottage movement: Design matters. A lot.

Before they set aside their concerns, most people — especially those who live nearby — need a demonstration of how these small-scale neighborhoods can add to the beauty and function of existing neighborhoods. And the tolerance of neighbors is essential, since cottage-scale communities need to be in places that offer the kinds of amenities already associated with high-value locations — access to work, transit, schools, shops and restaurants within walking or biking distance.

Simply put: The trade-off for living in small spaces is proximity to most daily needs not far outside your door.

Pacific Northwest architect and author Ross Chapin calls these kinds of communities “pocket neighborhoods” for obvious reasons. Before the Katrina Cottage movement cranked up, Chapin was demonstrating the market-rate niche for these sorts of communities in the right places. Now, he and some partners are applying the ideas of clustered single-family cottages to a multifamily setting:

Using a form of self-financing, they’ve adapted an old motel to 16 units for multi-generational, mixed-income home owners. Almost immediately, all sold out.

Similarly, R. John Anderson of Anderson|Kim Architecture and Urban Design has been working on combinations of attached and detached units in clusters that can be built in increments not so large that small developers and builders can’t compete with the big guys.

To help get more of these model neighborhoods on the ground, local and national non-profits — not unlike the ones that helped Bruce Tolar launch the original Katrina Cottage neighborhoods in Mississippi after the storm — are coming to the table to add value to potential deals with private developers and to help manage thorny issues with financing and qualifying candidates for rental units. That may be the next stage of accelerating pocket neighborhood growth.

Want to hear more about this stuff?

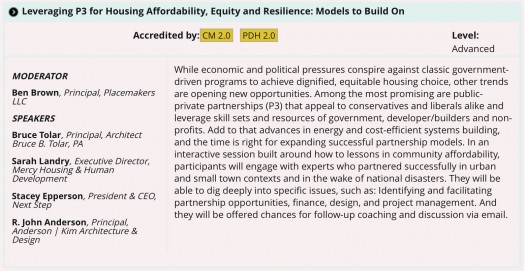

I’m moderating a panel with Anderson, Tolar and non-profit leaders Sarah Landry and Stacey Epperson on January 31 in Baltimore at the annual New Partners for Smart Growth conference:

And February 20-22, the Seaside Institute awards the Seaside Prize to Laurie Volk and Todd Zimmerman, pioneers in New Urbanist market research. They’ll be leading two days of seminars on “Neighborhood Challenges for a Re-Urbanizing Nation.”

–Ben Brown

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.