A Placemaking Journal

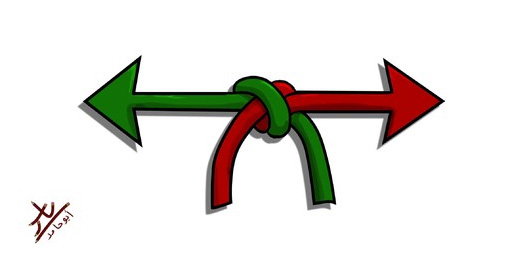

Talkin’ Right, Leanin’ Left: The ‘New Consurbanism’?

Here’s a quiz for you: What’s the “it” in these two quotes? And who’s talking?

It “is a radical, government-led re-engineering of society, one that artificially inverted millennia of accumulated wisdom . .”

It “offers conservatism a new venue, one where we can couple our desire for traditional culture and morals with a physical environment that supports both.”

If you’re like a lot of our colleagues in the business of advocating and planning compact, walkable, mixed-use environments, you might guess the first quote is a call to action from right-of-center defenders of conventional suburban development. The “it” must be a reference to the devil’s work of New Urbanism and Smart Growth.

Similarly, given some outspoken conservatives’ defense of suburbia as the purest product of market-driven forces, the “it” in the second quote surely must be in service to good ole, American, car-enabled sprawl.

Since you’re smart enough to figure out the challenge is a trick, you won’t be shocked to hear that the initial “it” in the first example stands for “America’s suburban experiment.” The quote is from Chuck Marohn in an October piece for The American Conservative.

Here’s a more complete excerpt:

America’s suburban experiment is a radical, government-led re-engineering of society, one that artificially inverted millennia of accumulated wisdom and practice in building human habitats. We can excuse modern Americans for not immediately grasping the revolutionary ways in which we restructured this continent over the past three generations–at this point, the auto-dominated pattern of development is all most Americans have ever experienced–but today we live in a country where our neighborhoods are shaped, and distorted, by centralized government policy.

The second quote is from a post last week on the same conservative mag site from William S. Lind. The “it” in that passage was “New Urbanism.”

What Lind wrote:

At root, New Urbanism is an attempt to bring back good things from the past that we have lost. That is what conservatives also seek to do, on a broader scale. New Urbanism offers conservatism a new venue, one where we can couple our desire for traditional culture and morals with a physical environment that supports both.

Cross talk between conservatism’s pragmatic wing and New Urbanist theorists has been going on for decades. I particularly like how Matthew Walther, a commenter on another American Conservative post, dubbed the mash-up: “The New Consurbanism.”

Lind is a fan of streetcars. He oversees The American Conservative’s Center for Public Transportation. And he was one of the authors, with Paul M. Weyrich and Andrés Duany of a white paper called Conservatives and the New Urbanism: Do We Have Some Things in Common?

Chuck Marohn is an engineer and infrastructure specialist who heads up the Strong Towns nonprofit and lectures about the “Ponzi scheme” of infrastructure finance. Marohn and Joe Minicozzi, an architect/planner/developer who studies the tax implications of land use, have been among the leaders of the show-me-the-money school of growth planning.

That particular corner of the New Urbanism movement has grown in response to the demand for data from those not entirely sold on the advantages of urbanism over sprawl. Given that the movement’s roots were in private sector responses to a missing niche in real estate development, the ROI perspective made sense to lots of New Urbanist practitioners and policy wonks. So there’s now a ton of research exposing the drain on public resources when it comes to building and maintaining suburban sprawl and similarly strong data-driven arguments for the bang-for-the-buck efficiencies of compact development from hamlets in the countryside to villages, towns and cities.

My PlaceMakers colleague Hazel Borys has summarized many of the studies here. Convinced of the efficiencies, federal agencies have tried to tie funding for planning and infrastructure on holistic Smart Growth approaches. Trade associations representing developers, builders and realtors have all acknowledged — at least at the national level — that there’s profit in building and redeveloping walkable neighborhoods and appealing civic space. And mayors and city staffers are increasingly forced to explain why they’re not paying more attention to analyses like those of Joe Minicozzi.

Here’s how author Charles Montgomery explained Minicozzi’s work in an excerpt of Happy City: Transforming Our Lives through Urban Design posted on Salon:

Minicozzi has since found the same spatial conditions in cities all over the United States. Even low-rise, mixed-use buildings of two or three stories—the kind you see on an old-style, small-town main street—bring in ten times the revenue per acre as that of an average big-box development. What’s stunning is that, thanks to the relationship between energy and distance, large-footprint sprawl development patterns can actually cost cities more to service than they give back in taxes. The result? Growth that produces deficits that simply cannot be overcome with new growth revenue.

So now that the numbers are in, it’s slam-dunk thinking everywhere that reversing sprawl is the way to go, no?

No. And the reason is that, despite all the hand-wringing about looming shortfalls in infrastructure funding, the systems charged with interpreting and implementing policies and funneling money through federal, state and regional bureaucracies are organized to keep doing what they’ve always done until they’re jolted into emergency rethinking. And so far, the emergency — especially at the end of the funnel where people live, work and vote — is not sufficiently painful to reverse the momentum.

Not yet. But we’re getting there. And thoughtful conservatives are likely to be valuable allies in turning things around. Still, there are some things we need to better understand.

If you’re one of those pragmatic conservatives, your perspective on taxing and spending demands that you take seriously the arguments of Chuck Marohn, Joe Minicozzi and all the others arguing for ROI tests for taxpayer subsidies. Which, despite whatever predispositions you might have about the elitist lefties in New Urbanism, puts you in their company. The fact that more conservatives aren’t leading the effort to change sprawl’s default setting suggests there’s something else going on besides rigorous logic.

My PlaceMakers compadre Scott Doyon and I have been suggesting ways to understand this gap between what makes sense and what ends up getting done in a series of posts about branding and storytelling. For instance: here, here, here and here.

Bottom line: Believing is seeing. We come to most discussions with a set of beliefs we’ll hold onto even when we’re confronted with facts that contradict what we say we believe.

Urbanists tend to romanticize the appeal of city life and understate the challenges of trying to build a life there without the talent, luck or resources to take advantage of what cities offer. Conservatives tend to romanticize rural and small town life without acknowledging the cultural isolation and the narrow range of financial opportunities.

What’s encouraging about the ways some conservatives are wading into the discussion about the future of communities is that they’re focusing their arguments at the higher level of values. Conservatives and liberals are far more likely to find common ground on values — on providing safe, nourishing places for children and seniors, for instance; or for expanding choices for quality housing, financial opportunities and ways of getting around.

Agreeing on values, on ultimate ends, allows for the discussion you want to get to — the one about means.

Listen to conservative opinionator David Brooks in a 2010 New York Times piece touting the views of British author Phillip Blond: “Essentially, Blond would take a political culture that has been oriented around individual choice and replace it with one oriented around relationships and associations.”

What would that look like in terms of policy-making? Brooks again:

Economically, Blond lays out three big areas of reform: remoralize the market, relocalize the economy and recapitalize the poor. This would mean passing zoning legislation to give small shopkeepers a shot against the retail giants, reducing barriers to entry for new businesses, revitalizing local banks, encouraging employee share ownership, setting up local capital funds so community associations could invest in local enterprises, rewarding savings, cutting regulations that socialize risk and privatize profit, and reducing the subsidies that flow from big government and big business.

Not a bad place for the left and right to meet up, eh?

–Ben Brown

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.