A Placemaking Journal

Irony and Inevitability: Stumbling towards accountable public policy

By Wednesday morning, we’ll know which political party gained and which lost ground in Congress. As for learning about the direction of federal policy and its short-term impacts in states, regions and local communities: Not so much. But not for long.

That’s because time is running out on the baked-in paralysis in Washington. Despite vows to pretty much stick to the same recipe for dysfunction by Senate and House candidates in the mid-term elections, something’s coming that seems likely to stir things up. Let’s call it reality.

Reality, after all, is the change-producing force in most of our lives. The roof leaks, the bald tires go flat, the note comes due. Money — and pain — talks; BS walks. If you want to see how that plays out politically in places where the time lapse between bad ideas and bad outcomes is shorter than in Washington, look to the states and cities.

Lots of eyes are on Kansas and its governor, Sam Brownback, who has the misfortune of running for re-election on his record. In July, 100 of the state’s Republican leaders pledged to back Brownback’s Democratic opponent in the mid-term election because of what the Washington Post called “a laundry list of reasons, including tax cuts (Brownback) spearheaded, cuts to education spending and his alienating some centrist members of the GOP.”

Here’s how George Packer, writing in last week’s New Yorker, put it: “Kansans were given a toxic dose of supply-side economics, and, whatever the results of next week’s election, the experiment has been a failure, politically and economically. Democracy, on its heels around the world these days, sometimes works pretty well.”

It appears, in fact, that the fiercest elements of the polarizing ideology that’s so occupied Washington is not even getting a try-out in governors’ races. According to Governing magazine, “19 Republican governors are up for re-election, but only two — in Idaho and Wyoming — faced anything approaching a serious primary challenge from their right, and neither of those challengers defeated the incumbent. That’s just 11 percent of GOP gubernatorial incumbents drawing a primary challenge from the right, compared to fully half of U.S. Senate incumbents.”

Of course, the lack of opposition from the right could mean that some of these Republican incumbents had sufficiently conservative credentials to protect their flanks. “But perhaps the most fundamental reason that Republican governors haven’t faced primary challenges,” said Governing,” is that state races are different from federal races. They often turn on different types of issues, such as education and infrastructure, that are more technocratic in nature and aren’t coherent enough to package into a red-meat national agenda.”

I’d quarrel with “technocratic,” since education and infrastructure issues are pretty fundamental red-meat issues on any political level. Could it be that the real difference between how ideas are contested on the state and local levels compared with the national debate is that when mayors or governors talk about schools, roads, bridges and broadband, they’re talking about investing real dollars in real places for projects likely to impact their constituents’ everyday lives?

It’s one thing to pull the plug on “waste, fraud and abuse” in some place we’ve never heard of, it’s another thing to lay off teachers in our kids’ schools or to stop fixing our bridges and roads. Big ideas that polarize politics in Washington don’t seem nearly as controversial as when there are local stakes at risk. That’s why mayors of coastal cities and county commissioners in drought-threatened agricultural areas are more ready for a conversation about climate change than legislators in Congress. As far back as 2007, 600 mayors from all 50 states and Puerto Rico signed on to an agreement to advance that conversation.

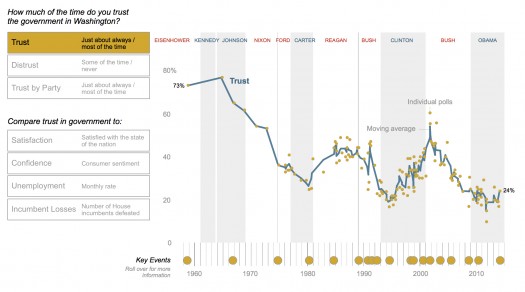

Voters are telling pollsters they’re more ticked off than ever at Washington. And the frustration has been apparent for decades — not just under the last couple presidents. Look at the graphic below (or click to enlarge) from 2013 polling by the Pew Research Center:

If you go to the Pew site and pass your cursor over the data points, you can see how frustration with government correlates with big events — the global and national economies, terrorism and war, etc. Many of those events were beyond the power of presidents and Congress to control, at least within the time frames in which they were elected. Yet they reaped the benefits or were tested by the correlations as candidates.

Clinton-era Democrats could stress, “It’s the economy, stupid,” even though delusions about controlling the economy out of Washington would haunt Democrat and Republican administrations alike in the years to come. George W. Bush was blindsided by a hurricane and a terrorism attack, which made him first look weak as an executive, then strong as a “mission accomplished” commander in chief, then weak again as the realities of war and the world economy exposed how unsavory a president’s options are.

Barack Obama was swept into office in 2008, in part by spinning the electorate’s denial of reality’s complexity into a message of change without pain. It didn’t take long for leftover wars and economic woes to discipline that thinking. Then came a world health drama gone all apocalyptic. All of which left voters feeling betrayed for their faith in the impossible and the opposition party feeling confident they could gain control of both houses of Congress with recycled Clintonian cynicism: “It’s THAT guy, stupid.”

Sometime around the turn of the new millennium all this was beginning to sound like a mash-up of Greek tragedy and Groundhog Day. All hubris and irony, over and over again. But the pragmatism required in cities and states is starting to look like an exit strategy.

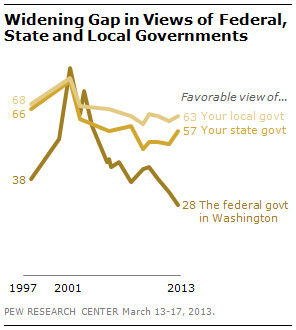

The glimmers of inevitability were already there, even in the survey numbers pointing to the decline in faith in the federal government. Look at this Pew graphic (http://pewrsr.ch/1wSma9J) comparing favorability ratings of federal, state and local governments.

The hierarchy of disdain has been consistent over the years. The closer you get to where public policy is tested in real places, the more respect there is for the policy-makers. What’s more, while the favorability ratings of the federal government have sunk to record lows over the last few years, faith in state and local governments has persisted and even risen a bit.

“Overall,” says Pew, “63% say they have a favorable opinion of their local government, virtually unchanged over recent years. And 57% express a favorable view of their state government — a five-point uptick from last year. By contrast, just 28% rate the federal government in Washington favorably. That is down five points from a year ago and the lowest percentage ever in a Pew Research Center survey.”

And here’s something else: Despite the broad brush of contempt with which the electorate paints the federal government, when survey respondents are asked how they feel about the work of specific federal agencies, they recognize things they like. The Pew poll of favorability ratings was taken in 2013, close enough to the unpopular federal government shutdown to remind folks in states and regions how federal programs and projects affected them:

“Despite highly negative views of the federal government overall,” says Pew, “the public has favorable views of many of its agencies and departments, which were closed by the shutdown. Majorities have favorable opinions of 12 of 13 agencies tested.”

(The outlier agency: The Internal Revenue Service. Surprise, surprise.)

This is why political wonks like Matt Yglesias at the Vox online site make a big deal about state races and ballot measures. The House and Senate races may capture the headlines, says Yglesias, “but a huge amount of what people care about — especially the ways in which government intersects with daily life — is in the hands of state and local officials. . . Especially at a time when Congress seems destined to remain broken and ineffective regardless of the results on Election Day, this is where the real midterms stakes are to be found.”

When it comes to many of the policies that matter most to planners and community development people, Tuesday votes on infrastructure investment in the states are likely to have way more impacts on families and businesses than who turns out to be Senate Majority Leader. Joseph Kane and Robert Puentes of Brookings produce a list of such items and underline the point:

On November 4, voters in several states and metro areas will have a big say over the future of their region’s infrastructure. With federal transportation funding running on empty and many areas continuing to tighten their purse strings, ballot measures are filling this void in investment.

All of this is not to say that state and metro politics is somehow more pure than politics as played by candidates for national office. It’s just that the lines of accountability are more distinct.

Because of gerrymandered Congressional districts and the power of primaries to activate the most extreme voters, Congressional candidates are rewarded for holding (or pretending to hold) reality-free perspectives. There’s always someone else to blame for things not working out: Members of the other party, the president, faceless bureaucrats, special interest lobbyists. Running for re-election — and they’re almost always re-elected — they can shake their fists at inside-the-Beltway forces that thwarted the ideas they championed.

Governors, mayors and others with executive branch responsibilities, on the other hand, don’t have those advantages. They’re more visible to voters on a day-to-day basis and more closely identified with programs they advocate. When their ideas flop, they’ve got explaining to do at the next election. So they’re quicker to abandon strategies that don’t show promise and more apt to strike deals to get results they can take credit for. Whether they like it or not, they’re accountable for wrapping their arms around problems and finding paths to solutions. On a deadline.

Which makes the days and weeks after Tuesday’s voting worth watching. Reality-based policies and programs in some states and metros will get the go-ahead, exposing the contrast with the reality-free versions persisting in Washington.

If we’re lucky, we’ll be nearing a tipping point. Because even effective leadership and smart policies in the states and local jurisdictions can’t succeed on the scales necessary to address the big problems without help from Washington, the pressure from below will force changes up the food chain.

Eventually, maybe, we’ll get closer to a place where the most workable definition of politics — “the art of the possible” — will seem less like a naïve fantasy.

–Ben Brown

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.