A Placemaking Journal

Going Viral, but Not in a Good Way

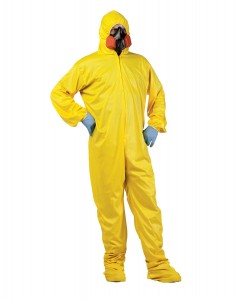

Hello, you in the hazmat suit. Can we talk?

Though no one can authoritatively predict, from an epidemiology perspective, what will happen next, Ebola reached new levels of infection in the body politic last week.

Republicans and Democrats seem pretty sure they’ve identified likely sources of toxicity. And it should come as no surprise that they’ve connected failures to control spread of the virus to the other guys’ policies and actions.

Republicans, especially those running for office, blame what they consider Obama’s failure to appreciate the Ebola threat from the get-go and to lead an all-out effort to keep it from crossing the Atlantic. Democrats, especially those running for office, point to GOP-driven budget cuts that likely inhibited the development of drugs that might have saved lives and contained the virus’s spread. But regardless of their political leanings, an awful lot of folks seem to agree on one thing: The struggle so far is yet another example of the failure of government to solve problems.

“We have no clue at this point how far Ebola could spread in the United States — and no reason for panic,” said The New York Times’s Frank Bruni in a weekend column, “But one dimension of the disease’s toll is clear. It’s ravaging Americans’ already tenuous faith in the competence of our government and its bureaucracies.”

Let’s think about this for a moment. What those bureaucracies are facing in Africa is the necessity for coordinating a multinational army of medical personnel and equipment in places where rudimentary conditions for controlling and treating contagion are minimal.

What’s more, while they may have theoretical knowledge of such threats and of response protocols — and perhaps even dry-run training in anticipation of such emergencies — few in the recruited army of practitioners have ever worked together in anything like these conditions and in anything like the required sense of urgency.

The same goes for all the people likely to be entrapped in the rapidly expanding territory of potential infection — workers in airports, bus and train stations, public health employees with little or no training or experience in infectious diseases on this scale. And on and on.

“You play the way you practice.” That’s a coaches’ cliché. But it applies to every activity in which we have a right to demand higher levels of performance. And we’re talking here about one of those events that’s impossible to practice under conditions a thrown-together team will face.

Name an activity where performance is measured, and note the tolerance — the expectation, even — for missteps along the way.

Sports? Games are organized around the necessity for somebody to make a mistake — miss a tackle in football, allow a goal in soccer, deliver a pitch a little too high and inside to a power hitter in baseball — and for a player or team to overcome mistakes to claim victory. Scores measure failure as reliably as success. No slip-up, no game.

How ‘bout business? In the small business sector, considered the beating heart of American entrepreneurial capitalism, less than half of start-ups are still operating after year five. Even among the huge firms, mergers, buy-ups and other reconfigurations — as well as outright closings — suggest how tough it is to manage change over time. Of the dozen companies that were part of the original line-up of Dow Industrials more than a century ago, only one name, General Electric, survives.

Yet in the case of government’s response to the Ebola challenge, consider what we’re requiring of stressed-out bureaucracies operating 24-7 in arenas of mind-boggling complexity: Out-of-the-box high performance, judged at any point along the learning curve against a standard of zero tolerance. Something we expect of almost no other individual or organization.

Ebola’s sudden emergence as a real threat that can kill innocents at home adds a whole new level of drama. But we’ve been honing, for the better part of four decades, a bipolar disposition about government, denying its ability to solve problems while demanding it solve more and bigger ones at the same time. The delirium is now baked into what passes for processes in congress and in many state legislatures.

Even though the stakes are less than life and death in the towns and regions where many of us work, the crisis of confidence and trust in government is taking a toll on our abilities as communities and regions to get anything meaningful done. Until citizens are willing to reinvest their trust — and their taxes — in plans and projects on loftier scales, maybe it’s time to focus on efforts that demonstrate transformative potential in smaller, more incremental ways.

Exactly three years ago this week, we wrote about the beginnings of this conversation by some of the leaders in New Urbanism.

Victor Dover, a CNU board member and veteran of the full range of New Urbanist adventures at just about every scale, was, with Duany, a Council keynoter. He provided the zen perspective, arguing that a forced slow down in development is not altogether a bad thing, especially if it allows designers and builders to be more respectful of context and complexity. What’s missing in many block-size New Urbanist projects from the go-go days, said Dover, is the advantage that comes with “intelligent incrementalism.” The slower pace allows for adapting future development stages to the experiences of stages that preceded them.

Watch Victor expand on the idea here:

Since then, DPZ and similar thinkers have launched the “Lean Urbanism” movement, with the challenge to planners and designers to “make small possible.”

This “right-sizing” of planning and design for the current era represents a strategic redirection of energy, at least among a committed sub-group of New Urbanists, with the same old ambitions to imagine and build better places. At some point, the need to scale up will return. But in the meantime, until leaders at every level become more comfortable resuming the partnership between government, private sector and non-profits that make big changes possible, small, incremental innovation that’s worth copying will be where the action is.

–Ben Brown

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.