A Placemaking Journal

One Chart to Explain Everything: You’re welcome

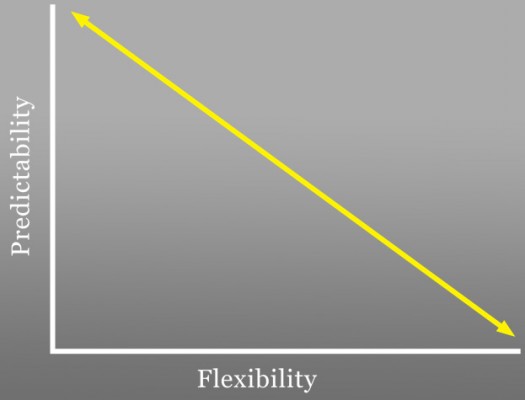

Welcome to what we all need: A single chart that explains everything. Okay, maybe not everything. But a lot of stuff, especially stuff related to making rules for growing businesses and communities.

It’s simple. And here’s what it illustrates: When you’re shaping rules to live by, the more you optimize flexibility, the more you sacrifice predictability. The higher you prioritize predictability, the lower your chances for flexibility.

This inverse relationship is important. Here’s why:

Just about everything we screw up as individuals and as organizations has to do with our determination to optimize both extremes. We yearn for maximum predictability in the wider world while reserving maximum flexibility for our own choices.

The temptations are understandable. Take predictability, for instance. It’s the dream state for planning. Ask any strategic planner, any executive, any investor their fondest wish, and they’ll say, “to know the future.” If you know what’s going to happen, planning’s a piece of cake. You can hire and fire with confidence, assure cost-effective budgeting for every project and be a hero manager for perpetuity.

Unfortunately, despite the claims of brokerage houses and telephone psychics, the ability to predict the future is a pipe dream. So we settle for trying to understand as many of the future-determining variables as we can and for using what we think we know to influence events to our advantage. Which also turns out to be beyond our grasp most of the time, especially in those times that require understanding and adjusting to complex challenges with hard-to-foresee implications. Think climate change, the global economy, parenting.

And what do we do when the lack of predictability in the wide world frustrates us?

Often, the instinct is to double down on command/control: Clamp down on the rules and drive out the heretics. When decision-making is in the hands of a few — kings and oligarchs, say, or charismatic CEOs — predictability purchased at the cost of suppression of competing perspectives doesn’t end well. The history of nations and commerce is full of examples. And as a result, democracies born out of revolution are hyper-vigilant when it comes to investing authority or regulating rights.

The instinct for organizational control, however, doesn’t go away. It’s just distributed among bureaucracies that are accountable for dealing with the implications of uncertainty in day-to-day situations, yet lack the authority to make rules and rule enforcement more responsive to the realities they face. That’s where the petty tyrannies reside in America nowadays, in the power gap filled with defensive policy-making.

Haul cabinet secretaries or county managers before their elected bosses to drill them about fraud and waste, and you can bet rules and rule-monitoring, along with the costs of doing business, will multiply. One off-the-cuff memo from a private-sector CEO to department heads will ripple through every level of the organization, shifting the notions of what workers will be held accountable for and changing the enterprise’s competitive position, often in unanticipated ways.

Nobody seems to get this dance right. Over time, nations emerge and fade. A tiny minority of companies survive under the same name or in the same business for more than a few decades. Historical post-mortems that seek to identify the decisions that led to doom are subject to so many revisionist analyses that even when lessons learned enjoy some sort of rough consensus, it’s often too late to apply them in a new context. Which only amplifies the anxiety response to an increasingly unpredictable environment.

That’s when another instinct kicks in. Uncertainty inspires retreat. We seek safety where we believe we can repair the connections between cause and effect, between what we plan and what happens when we act on our plans. The higher our levels of frustration, the tighter we draw the borders that define what we hope we can control. We focus on what happens in our own home, in our own neighborhoods, among our own tribe of believers. It is NIMBYism writ large with long-range planning shrunk to “Don’t Tread on Me.”

It’s in this environment, when we sense rising chaos and organizational dysfunction, that the opposite extreme in the graphic seems so appealing. If top-down decision-making is inherently flawed, then the answer lies in maximizing bottom-up flexibility. Flexibility delivers all the great stuff that predictability-focused organization is not so good at. Flexibility is about freedom. It clears the way for innovation, for the entrepreneurial spirit.

And for the most obvious flops in our personal and organizational lives.

When I covered sports as a newspaper reporter, I got into a discussion with a highly successful football coach about his obsession with control. By the time a coach reaches the upper tiers of his profession, he or she has experienced hundreds of ways to lose. So they become students of failure, of where they missed opportunities to choose a better way to prepare a team or respond in a game situation. They hate surprises, even though they can’t think of many contests where they weren’t surprised at some point. They know that talented players will at some crucial moments in a contest improvise with success, perhaps even with game-winning success. But that’s not something they can control. And coaches are control freaks. So they drill their teams for near-instinctual responses to situations in order, they hope, to minimize the necessity for innovation. To control what’s within their power to control.

I remember what the football coach told me about strategies for optimizing flexibility, for withholding commitment to rules, for keeping an open mind. “Well, I guess an open mind can be a good thing,” he told me. “But you have to be careful that your mind’s not so open that your brains fall out.”

When it comes to espousing freedom, diversity and resistance to authority, we’re sometimes in danger of letting our brain matter escape. Name a successful enterprise of any sort, and it’s likely to have required co-operation by those who recognized that achievement of goals were more predictable if individuals worked together than if they designed and attacked tasks individually. The bigger and more complex the goal, the greater the degree of organization and the greater the requirement for agreed-upon rules. In fact, a key strategy in any sort of competition is to frustrate an opponent’s capacities to organize. “Divide and conquer” is not an empty phrase.

So back to the chart.

If we’re to increase the likelihood of predictable outcomes, yet accommodate enough flexibility to respond to change, we have to position policies — whether we’re talking about zoning or some other regulatory framework somewhere along that diagonal line. Where depends upon appetites for the trade-offs required as we move along the line. The desire for greater degrees of predictability means less flexibility. More flexibility risks greater unpredictability.

Where we don’t want to be is at either end of the diagonal, sacrificing opportunities for collaborative success to preserve the fantasy of absolute freedom or forsaking adaptability over time for the fantasy of absolute stability.

–Ben Brown

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.