A Placemaking Journal

Industry, Infrastructure and Intermodalism—Still Mixed Up on Special Districts?

In her September 2011 blog, Special Districts Getting All Mixed Up, Hazel Borys questioned why we treat large format areas with distinctive uses, such as manufacturing or aviation, as “special” to the point of exclusion from our efforts to integrate all urban land uses and activities into a spatially coherent whole, ending with an inspiring contemporary example of planned “strict integration” of land uses in the corridors and boulevards connecting the El Paso International Airport to the city.

Traditional zoning, such as implemented in Chicago in 1923 was defensive, leading to separation of land uses and activities from people. Defense was needed to socially separate people from unhealthful conditions—and the definitions of what impaired public health or well-being ranged from what was tangible and measurable including industrial emissions and noise to the intangible and unmeasured social classifications such as race, class and country of origin.

A similar challenge to urban character was made by leading planners and traffic engineers—for example, there’s a chapter in the Los Angeles comprehensive street traffic plan done in 1924 by Harland Bartholomew, Frederick Law Olmstead Jr. and Charles Henry Cheney finding that “The Promiscuous Mixing of Traffic” is a top cause of street congestion which a cynic might equate to an anti-miscegenation law.

But re-integrating the separated parts of our cities and regions demands that we affirm what’s possible. The two innovations required are (a) a shift from describing only what we want to see and experience to include a set of accountable outcomes, and (b) recognize that we have tools such as transects and form-based codes to help shape communities with respect to residential, commercial, and some recreational and municipal services; but we don’t have the tools to help shape land that has traditionally been “off-grid.”

It’s been too easy to assume that land uses in legacy American cities were all “on-grid,” that is, located within a logically ordered network of streets and other necessary civil infrastructure, such as water supply and sewers, and associated infrastructure such as that needed for providing electricity, natural gas and telecommunications.

But much of even the most revered of such gridded reputations such as those of New York and Chicago, for example, are easily punctured by a review of what the map tells us.

Taking a Closer Look in Chicago

We fortunately have an extraordinarily detailed compendium of block-level data and mapping published by the Chicago Plan Commission, Land Use in Chicago, giving us a baseline 1940 snapshot.

If we assume that all single-family and multi-family residential, and all commercial land uses are on-grid, as are all streets and alleys, that would give us 53.3% of all land in the city meeting this definition; even if we assume that all 21.4% coded as “vacant” were on-grid, that only brings us to 74.7% of the total land area. What about the rest?

6.9% was coded as industrial, 7.6% as railroads, 4.8% as parks and playgrounds, 3.3% as other public institutions, and 2.7% as waterways. Some play-lots were on-grid as were a number of industrial zones principally housing job-shops serving larger industries; and with enough work we could determine a rough estimate of the size of these gridded lots. And similarly, a large chunk of the multi-family residential was property of the Chicago Housing Authority, which less than two decades later would become several times larger to accommodate the displacement caused by the routing and construction of the limited access highway system.

One result of this culture of separation was the banishing of much-needed work to less accessible places; another was to limit the availability of public funds, shortsightedly, for infrastructure needed to support an urban industrial city. Burnham and Bennett’s Plan of Chicago took a distinct approach to both transportation and to infrastructure: the Plan focuses much attention on inter-city transportation and is perhaps the first modern regional plan for high-capacity highways, but pays little attention to internal circulation other than to call for “coordination.” Simultaneously, an agreement to elevate all 712 miles of rail track within the city limits significantly increased the functionality of the city’s rail networks and rail yards, setting the stage for (a) modernization of these systems and (b) development of specialized facilities and organizations adapted to the needs of dense urban industrial economy, and it is to these latter that we turn our attention.

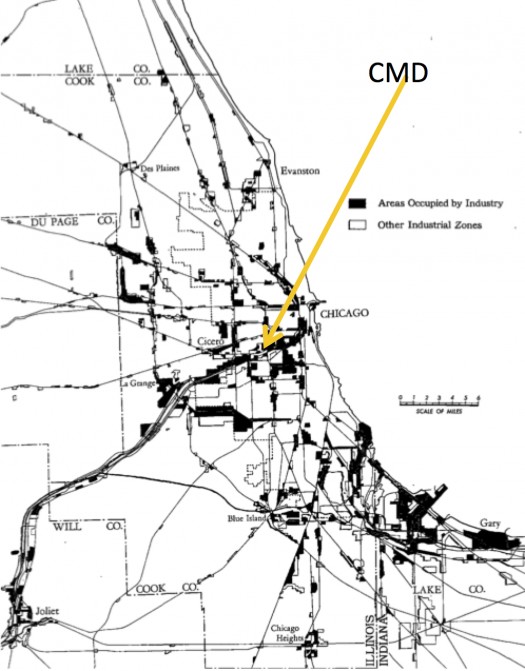

Unlike the company town facilities for which industrial Chicago was known, such as the United States Steel South Works, the Pullman Company, and the Gary IN USS Works and surrounding communities, let’s examine some successful adaptations, with four examples. The first is the Central Manufacturing District (CMD), the second is the south suburban Green Time Zone, the third is the Fulton-Carroll Industrial Incubator, and the fourth is the creation of Planned Manufacturing Districts or PMDs.

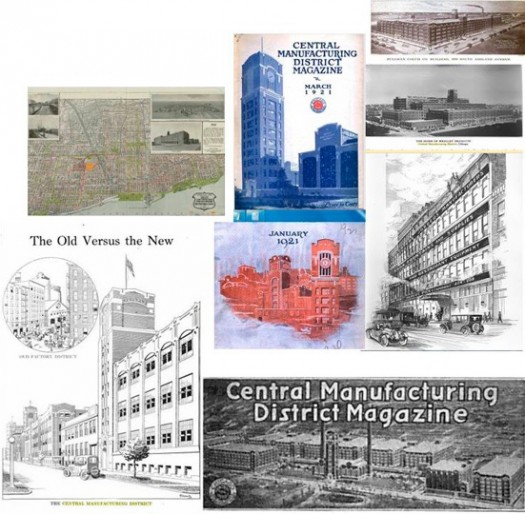

Central Manufacturing District

The brainchild of Frederick Wood Prince, CMD was just north of the Chicago Union Stockyards, and is arguably the forerunner of the contemporary “industrial park.” Prince purchased the Chicago Junction Railway in 1902, realizing that the adjacent Union Stockyards were fully occupied by 1900, so that any expansion would need to be north and west of the yards. The railroad, took responsibility privately for all civil infrastructure, a power system, a bank, a business club open to district residents, express and telegraph offices, a central telephone switchboard, a medical staff and a traffic bureau.

Starting in 1908, it had grown to 300 serviced acres and over 200 industrial tenants, many of who exercised purchase options, by 1920. In addition to the factories, warehouses and utilities, innovations included a union freight terminal serving all residents and all railroads operating by trackage rights over the Chicago Junction, one of the Burnham Plan proposals; a joint Montgomery Ward warehouse linked to the union freight station; three supply warehouses for the U.S. Army, a cold-storage warehouse for the federal government reportedly the world’s largest at the time, and specialized freight tunnels for electric trains and conveyers linking the main buildings.

The surrounding Chicago neighborhoods of McKinley Park, Bridgeport and New City (also known as Back of the Yards), had an aggregate population of 38,627 households on 3712 acres, 10.4 households per gross acre with 80% living in 1-4 unit buildings, and 10 percent of the 1-4 unit buildings listed as “with business.” The principal CMD buildings of exceedingly urban design fronted Pershing Road or 39th Street, an east-west orientation, while heavy industry itself was behind these elegant structures connecting directly to the rail terminal and interchange facilities and the working South Branch of the Chicago River.

Of these designs by S. Scott Joy, urban historian Carl Condit noted they provided “…a formal unity that confers harmony without monotony.” At peak the CMD + Stockyards tenants directly employed 40,000 on roughly 300 acres, and it would be interesting to see what the land consumption would be to employ a similar amount in an analogous configuration today, but I would say that CMD and the Chicago Junction Railway had comparable functionality to newer intermodal facilities operating in exurban locations such as the the Centerpoint Yard near Joliet Il. but operating on 80% less land (the Chicago Junction Railway in 1920 handled 1.5 million freight cars per year under its own power and another 1,000,000 cars powered by trunk lines operating over CJR’s tracks).

The District also acted as a credit facility for potential area homeowners, arranging for the construction and financing of homes “at cost,” specifically, an organization known as the Home Building Real Estate Improvement Corporation received subscriptions from 34 firms and individuals in the District, and employees of those subscribing firms were given first chance to purchase the new homes constructed, all of which were in 2-unit buildings.

Financial arrangements between the district and its residents included 3 types: (1) the district leased the land and the building, with tenants paying annual rent; (2) the district sold the land outright and erected the buildings; or (3) the district leased the land and the building, with tenants paying 25% of construction cost upon occupancy with the balance remitted as an annual rent over 10-15 years. These arrangements enabled the duplication of the CMD in suburban Chicago and a string of others nationally under the CMD brand nationally starting in Los Angeles, and by a growing list of competitors over the decades.

Much urban redevelopment today is targeted to areas adjacent to legacy rail networks and yards and to former industrial areas dubbed brownfields. Most if not all of these confront the challenge of finding resources to service a dense mixed use character, and there is much to be learned from these earlier experiments to intensify mixed-use development and industry around efficient and space-intensive rail yards. Arguably, CMD became the economic locus of the area in which it was located, and good planning enabled industrial administrative and warehousing and distribution functions to buffer heavier manufacturing and shipping and their externalities from the surrounding neighborhoods, all of the latter of which were further anchored by their commercial mixed use boulevards which came conveniently with their branches and stops of the largest street railway network in the world.

Since every building at CMD was built with its own spur track and since all rail transport was controlled by the District, rail shipping needed no transshipment to street vehicles (read trucks) for direct delivery. District shipping management was indexed to a 24-hour “unit” with all deliveries and switching within that period of time, so that all yard and switch track operations were “cleared” once a day. The efficiency of the system resulted not from the density of the facilities, which by themselves would add to congestion, but from the density and management of the rail facilities planned logically and jointly with the density and management of the tenant industries and their buildings. Scott Joy’s designs were templates for a District-enforced set of quality design standards which were adhered to successfully.

CMD successfully bridged gridded communities and thoroughfares while providing the technological means of keeping the off-grid heavier manufacturing and transportation operations logically and efficiently organized.

This small area continuum from neighborhood-administrative-distribution-heavy manufacturing and shipping is amenable to form-based coding.

Urban Strategy Can Be Informed by This History – Cargo-Oriented Development

The redevelopment of a former oil refinery in SW Illinois, informed by experience at Coed Darcy in Scotland led by the Princes Foundation for Community Building, is similarly based on a kind of transect in which a small traditional downtown is buffered by a campus-like transition zone to heavier manufacturing and shipping.

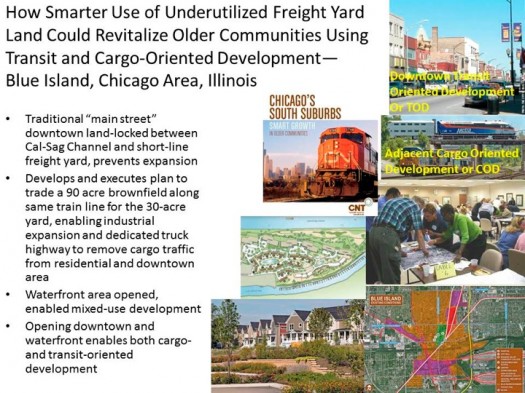

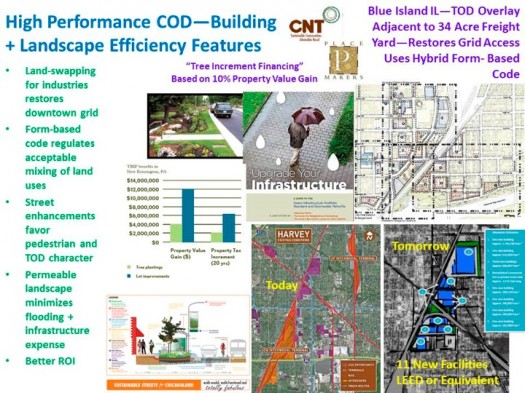

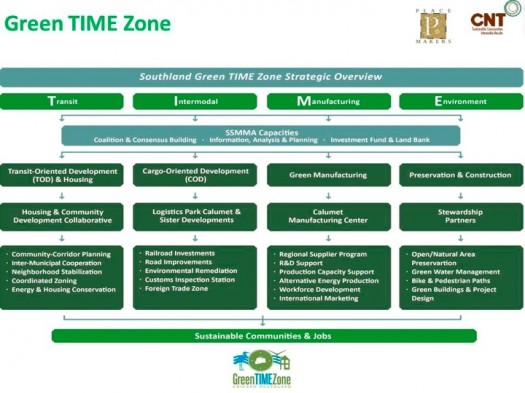

Work like this in the south suburbs of Chicago, now backed by a 42 suburb network known as the Green TIME Zone (where TIME stands for Transportation, Infrastructure, Manufacturing and Environment) has already leveraged significant commitments to legacy downtowns’ expansion triggered by new land use agreements and innovative “swaps” intended to enhance the area’s mixed use character and facilitate modernization and growth of both the residential, transportation and commercial industrial sectors there.

The GTZ has also created a fund to help finance the land acquisition and pre-development infrastructure costs associated with cargo-oriented and transit-oriented redevelopment; Cook County used a HUD Section 108 loan guarantee against future Community Development Block Grant apportionments for a cargo- and transit-oriented land bank; and the Illinois General Assembly approved a new kind of tax increment financing for the target area against the income tax anticipated from new jobs created, in contrast with the typical TIF against anticipated property tax receipts. The GTZ, with support from the Economic Development Administration, has also designed a supply chain quality certification system for area businesses which includes both production and services quality and workforce development systems.

While major public investment and attention on freight transportation improvements in Chicago is focused on a project to grade-separate highways and railroads, known as CREATE, by contrast these localized “cargo-oriented development” or COD investments aimed at the last-and-first mile, demonstrably increase the efficiency of the landscape, and of the activities located at these developments, resulting in a reduction of the cost of living and the cost of business, an increase in taxable value per unit of land, both short and long-range job creation, and the long-term support for economic supply chains needed for sustainability.

And they are also making use of home-grown innovations by local manufacturers to replace diesel cargo equipment with clean-powered electrical equipment and to use both information technology and better geometry to stack container freight efficiently, again reducing the amount of land required, keeping these facilities and their workforces co-located and better connected. Although off the usual radar screens, investments intended to move freight in such facilities at potential “net zero” emissions for both transportation and buildings are advancing in southern California, where the lead regulator has called for this kind of strategy as a condition of approving intermodal expansion.

At the new BNSF yard in Memphis, in Baltimore in preparation for expanded shipping via the almost completed Panama Canal expansion. If Calgary in oil-rich Alberta can connect the dots with that province’s wind-electric farms to produce a zero-emissions light rail system, dubbed “Ride the Wind,” why can’t we see and act on these connections to facilitate net zero cargo and passenger transportation too?

Innovations in the 1980s: Planned Manufacturing Districts and Industrial Business Incubators

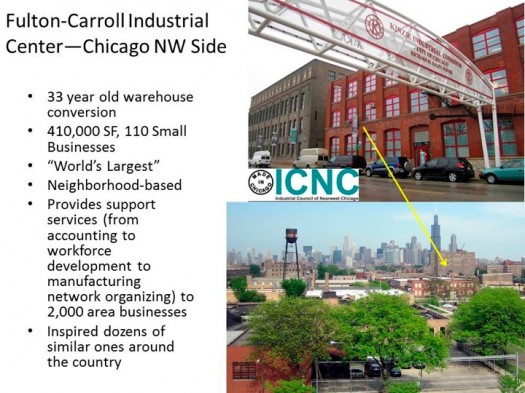

As of October 2006, approximately 1,400 business incubators operated in North America, including 1,115 in the U.S. A business incubation program’s main goal is to produce successful firms that will leave the program financially viable and freestanding. Critical to the definition of an incubator is the provision of management guidance, technical assistance, and consulting tailored to the needs of new enterprises. This case study is of a place-based, manufacturing oriented incubator on the northwest side of Chicago operating within a re-purposed set of warehouses in a single block in a walkable urban grid.

A group of business owners came together in 1967 to address the deteriorating economic and social conditions on the Near West Side, namely crime and garbage pick-up. The Industrial Council of Northwest Chicago was created out of this need to join together and protect the interests of business and continues that work today.

ICNC strengthened its role as a business advocate in the 1970′s and 80′s. In 1980 it received a grant to purchase several large industrial buildings which enabled it to start one of the first (and largest) business incubators in the country. Soon thereafter, a new 501(c)(3) organization was formed, the Kinzie Industrial Development Corp (KIDC) in an effort to expand and broaden the group’s economic development mission (KIDC operates under the same board, management and staff structure as ICNC). Key developments in ICNC’s history include a 1998 Planned Manufacturing District (q.v. below) —created by the City as a means of ensuring that businesses/jobs are not pushed out of the area by either residential or retail, both of which are prohibited in the PMD and Tax Increment Financing district for the purpose of investing local tax money back into the area.

Today FCC provides space and business assistance to over 120 small business tenants in its 410,000 square-foot incubator. Created by a federal grant in 1980, FCC was one of the first five business incubators in the nation. Its goal remains assisting companies move toward long-term success.

Great Space in a Single Block

Today’s services include—$5.00-$9.00 per square foot rents (250 to 8,000 square feet); Flexible leases – short & long term; Start-up friendly – 1st month rent free (see start-up services below); Great location – near Loop & CTA (Green line, Damen bus), highways (I-290, I-55); Full access to facilities, Meeting rooms, Training Room Usage, private mail boxes; Technical Assistance Center – delivery services, postage, internet, FAX, copier; Business Resource Center – entrepreneurship library & software; Electronic Key System & security cameras; Use of 13 freight elevators & docks; On-site property manager, maintenance staff, business counselors, etc.; Recent $3 million investment in new windows and energy savings.

Support Services (at no extra cost – all funded by grants) including; Financial and Business growth assistance; Small business development center onsite; Free onsite computer classes; Employee placement service; Reimbursement for Employee training (50%); Link to Government programs and services; On-site workshops and seminars; Tenant networking and Social events…

Tenants take note! Does this sound like your lease?

Planned Manufacturing Districts

In 1988, the Chicago City Council joined Boston MA and Portland OR as leaders in approving the 115-acre Clybourn Corridor Planned Manufacturing District, protecting 24 industrial firms employing 1,400 workers; followed by the 170-acre Elston Corridor PMD and the 146-acre Goose Island PMD in 1990, the Kinzie Corridor in 1998, a similar district along the Chicago River at Chicago and Halsted in 2001, and several more in 2004.

The PMD modified the zoning map by dividing the targeted districts into core and/or buffer zones; industrial uses are concentrated into core zones where residential and commercial uses are prohibited, while the buffer zone is reserved for commercial and industrial uses. One outcome in creating PMDs was to take zoning decisions in manufacturing areas out of the hands of local aldermen by creating distinct zoning classifications as opposed to amendments to the zoning maps; this sent a signal to speculators that PMDs were not subject to traditional rezoning, leading to more stable property values and subsequent reinvestment by the area’s steel mills, scrap processing and other industries.

The idea to create PMDs was created by the Local Economic and Employment Council (LEED, renamed as the North Branch Works)), a neighborhood-based group of community organizations and business leaders operating in the industrial areas spanning the near north branch of the Chicago River.

While the conservative voice of the Chicago Tribune could claim in 1997 that “Communism may have fallen but Chicago still has central planners who know best where industry must go,” a count of job changes in the PMDs by University of Wisconsin professor Joel Rast (full disclosure—a CNT alum) showed reason for optimism. Within the Goose Island PMD, a partnership between the LEED Council created the Goose Island Industrial Park, and using innovative state regulation and tax increment financing for environmental cleanup, the park attracted Republic Windows and Doors, River North Distributing, and Federal Express, growing jobs from 950 workers in 1990 to over 2,000 in 2004; and more recently landing the 600-job Wrigley Company R&D campus facility, very recently converted to the Wrigley headquarters which relocated to this transit-oriented, near north side industrial park.

In response to continued questioning in 2007 of the value of this zoning innovation, former Alderman Edwin Eisendrath, a principal sponsor of the PMD legislation, noted that while large heavy-industry steel casting tenant A. Finkl and Sons had been recently sold, to date the legislation had bought on average at least 20 years of extra economic life. Finkl Steel is currently in process of re-locating, but within the City of Chicago, to an industrial site formerly occupied by another steel firm on 93d Street, at a rail asset-rich location near the intersection of the high-frequency Stony Island and 95th Street bus corridors easily linking to high-speed, high frequency Chicago Transit Authority and Metra Electric rail transit. This follows in their tradition: the company is proud of running on 100,000 tons/year of scrap steel, so efficiently it was the first integrated steel processor in North America to receive ISO 9000 certification; as part of the commitment to the principles of the Planned Manufacturing District, it not only paid for on-site landscaping and heritage-oriented placemaking, but created a landscaping subsidiary who’s profits were reinvested in surrounding communities.

Looking Ahead

Businesses in PMDs are not immune from major economic forces such as globalization, and Rast cautions that new workers in Chicago’s PMDs are as likely to work in warehouses as in factories.

But we can’t help noting that with an uptick in domestic manufacturing over the past several years, and significant new commitments to organizing leadership region-by-region to boost manufacturing success, there is an increased demand for industrial land with competitive amenities and good workforce access. To date, the framing of this proposition is spatially diffuse, with blunt analytical tools used by university and think tank researchers spanning mega-regions, not focused on industrial neighborhoods in core central cities and central counties.

Let’s Get Together

The reality of off-grid assets is too important to ignore. The list includes without being limited to:

• Airports and aviation facilities—529 airports with scheduled passenger service and several thousand more general aviation facilities

• Freight yards—3,400 in the continental US of which 61 percent are within metropolitan boundaries

• Urban waterways—thousands of miles of inland waterway were recently designated as America’s Marine Highway, making priority access to credit and market development feasible

• Passenger transit—too often, passenger transit is surrounded by other public facilities such as bus marshaling areas and parking that make it less than attractive; and transit has been routed too often through least-purchase cost right of way that runs through the kinds of areas listed above. A large fraction of the nation’s 3,400 existing and 600 developing transit stations meet this description

• Public housing developments—continue to be decentralized by a variety of scattered site strategies

• Vacant land and parklands—tight budgets and chaotic weather increases the demand for land to perform the extra function of “catching raindrops where they fall and putting them to work”

• A smarter grid for distributed energy and infrastructure resources—electrical utilities are exposed to excessive peak demand and the culprit is the lack of a diverse load, in turn a function of separate use land coverage. We can “re-tune” our grids to power them with diverse loads if we’re willing to be increasingly “all mixed up” when it comes to community character.

• Libraries and parks and transit—colleges are helping drive core reinvestment, as parents discover it pays to purchase a nearby condo or rent a nearby apartment for their kids; park districts find it’s possible to offer quality concessions without destroying essential public character; local libraries in the meantime, like local mass transit stations, are still mired in antediluvian rules paradoxically labeled “joint development” that limit the use of public funds to what can be put on a public right-of-way and then restrict the resulting use to non-commercial activity.

• Distributed resources and eco-districts—utilities are discovering that delivering a combination of alternative energy supply and resources to reduce energy peak demand at a neighborhood scale can pay; others are discovering that electrifying non-building uses such as transportation can provide increased reliability for the entire neighborhood, and using the same net-metering mechanism enabling resale of rooftop-generated energy, turn all full time consumers in a target district into at least part-time producers. Check out Eco-Districts Conference being held in Boston, November 2013.

What’s needed is a strategy to connect these dots—can we make economic performance count when attempting to connect these off-grid assets to their adjacent communities? Do we really need to put these “off-grid” and industrial activities into “special districts” when planning, zoning and coding for improved urban character?

As we consider the answers to these and other such questions, let’s be mindful of lessons stated by Sally Chappell in reviewing the history and function of complex rail stations and their tandem facilities.

“Architects, engineers, public officials and railroad managers involved in designing the stations refused to concede that technology and culture could and should be separated—much less treated as mutually exclusive…whether one arrived in a city to conduct government or business negotiations or for personal reasons…deep human feelings found satisfaction in the spaces of a railroad station. The buildings, streets, bridges, small parks or squares erected in the spirit of this idea may have suffered neglect, misinterpretation and abuse over the years, but the vision of urbanity both technically up-to-date and culturally meaningfully that was embodied…has persisted.”

Stay tuned…

–Scott Bernstein

Scott is President and CEO of The Center for Neighborhood Technology (CNT). The CNT is the national non-profit that has pioneered ways to quantify the advantages of linking transportation, land use and housing strategies with economic development and community affordability. It is the leading national provider of web-based analytic and data access tools for local area planning intended to meet the triple bottom line of improved quality of life, improved economic quality of place, and environmental resilience. CNT is a winner of the 2009 MacArthur Foundation Award for Creative and Effective Institutions, and Planetizen lists Scott Bernstein as number 27 in its poll identifying the Top 100 Urban Thinkers of the past century.

References

• “Airports and Industrial Buildings,” The American Architect, Vol. 136, No. 2573, July 20 1929

• “Central Manufacturing District Has Forged to the Front—Old Section of Southwest Side is Development,” in Chicago: The Great Central Market, Chicago Association of Commerce and Industry, 1923, pp. 99-100

• Arnold, Bion J., Report on the Re-Arrangement and Development of the Steam Railroad Terminals of the City of Chicago, Citizens’ Terminal Plan Committee, November 18 1913

• Ballon, Hilary; The Greatest Grid : The Master Plan of Manhattan, 1811-2011; Columbia University Press and the Museum of the City of New York, 2012

• Bernstein, Scott, Form Follows Finance, Presentation at Congress for a New Urbanism Workshop on Removing Barriers to Financing Mixed Use Development, January 18, 2011, at https://dl.dropboxusercontent.com/u/19641226/Form%20Follows%20FInance%20January%2018%202011.pptx

• Bernstein, Scott; Re-Placing the Region—Social Capital and the Future of Community, Community Development Technologies Center, December 1999

• Bernstein, Scott; Using the Hidden Assets of Cities and Regions to Build Sustainable Communities, 1999 at www.cnt.org

• Borys, Hazel, Special Districts Getting All Mixed Up, PlaceShakers, September 16 2011 at https://placemakers.com/2011/09/16/special-districts-getting-all-mixed-up/

• Burnham, Daniel H. and Edward H. Bennett, Plan of Chicago, Prepared Under the Direction of the Commercial Club During the Years 1906, 1907 and 1908; reprinted by Da Capo Press, 1970

• Burnham, Daniel H. Jr. and Robert Kingery, Planning the Region of Chicago, Chicago Regional Planning Association, 1956

• Chandler, David et. al. Chicago’s Green TIME Zone, Chicago, Center for Neighborhood Technology, 2012 at www.cnt.org/repository/GTZ.pdf

• Chandler, David et. al. West Cook County Cargo Oriented Development and Transit Oriented Development, 2013, at www.cnt.org/repository/WestCookCODTOD.FINAL.pdf

• Chappell, Sally A. Kitt; “Urban Ideals and the Design of Railroad Stations,” Technology and Culture, Vol. 30, No. 2, pp. 354-375

• Condit, Carl W., Chicago 1910-29: Building, Planning and Urban Technology, University of Chicago Press, 1973, pp. 136-144 and ff. 56-58 on pp. 174-175

• Culhane, Kerry, “Making Connections: Planning for Green Infrastructure in Two Bridges,” Urban Omnibus: The Culture of Citymaking, Architectural League, New York, Aug. 2012 at http://urbanomnibus.net/2012/08/making-connections-planning-for-green-infrastructure-in-two-bridges/ and http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2007-01-21/news/0701210471_1_clybourn-corridor-zoning-planning

• Eisendrath, Edwin Jr., “Success of Planned Manufacturing Districts,” Chicago Tribune Op Ed, January 21, 2007 at http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2007-01-21/news/0701210471_1_clybourn-corridor-zoning-planning

• Foster, A. H. , The Central Manufacturing District: Modern Industrial Engineering, Dissertation, Northwestern University College of Engineering, 1928

• Gilbert, Richard and Anthony Perl, Transport Revolutions: Moving People and Freight Without Oil, Earthscan, London UK, 2008

• Land Use in Chicago—Volume Two of the Report of the Chicago Land Use Survey, Chicago Plan Commission and Works Progress Administration, August 10 1943, pp. ii, xv, xvi, 232-233, 248-253

• Moody, Walter J., Wacker’s Manual of the City of Chicago: Municipal Economy, Chicago Plan Commission, 3d ed. 1920

• Muller, Edward K., “From Waterfront to Metropolitan Region: The Geographical Development of American Cities,” in Howard Gillette, Jr. and Zane L. Miller (ed.), American Urbanism: A Historiographical Review, Greenwood Press, 1987, pp. 105-134

• Ohland, Gloria; Chicago’s South Suburbs, Chicago, Center for Neighborhood Technology, 2011 at www.cnt.org/repository/SS-Case-Study.pdf

• Plumbe, George E., Chicago: The Great Industrial and Commercial Center of the Mississippi Valley, Civic-Industrial Committee of the Chicago Association of Commerce, 1912, pp. 51 and 65-75

• Rast, Joel; Remaking Chicago: The Political Origins of Urban Industrial Change; Northern Illinois U. Press, 1999

• Rast, Joel; Curbing Industrial Decline or Thwarting Redevelopment? An Evaluation of Chicago’s Clybourn Corridor, Goose Island, and Elston Corridor Planned Manufacturing Districts; University of Wisconsin Center for Economic Development; 2005 at http://www4.uwm.edu/ced/publications/pmdstudy1.pdf

• Raymer, Walter J., Track Elevation Within the Corporate Limits of the City of Chicago to December 31st 1908, Track Elevation Department of the City of Chicago, January 1 1909

• Schwieterman, Joseph P. and Dana M. Caspall, w. Jane Heron (ed), The Politics of Place: A History of Zoning in Chicago, Lake Claremont Press, 2006

• Stockwell, Clinton; “Chicago Manufacturing District” in Grossman, James R., Ann Durkin Keating, Janice L. Reiff; Encyclopedia of Chicago, University of Chicago Press with Newberry Library and Chicago History Museum

• Tchen, John Kuo Wei, New York Before Chinatown: Orientalism and the Shaping of American Culture 1776-1882, Johns Hopkins Press, 1999

• The Railway Terminal Problem of the City of Chicago, Addresses Before the City Club of Chicago, September 1913

• Wirth, Louis and Eleanor H. Bernet, 1940 Local Community Fact Book of Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1949

• Zardini, Mirko; Sense of the City: An Alternative Approach to Urbanism, Canadian Centre for Architecture and Lars Muller Publishers, 2005

• Zumerchik, John, Jack Lanigan Sr., and Jean-Paul Rodrigue, “Incorporating Energy-Based Metrics in the Analysis of Intermodal Transport Systems in North America,” Journal of the Transportation Research Forum, Vol. 50, No. 3, Fall 2011, pp. 97-112

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.