A Placemaking Journal

Identifying the “Sabermetrics” of Urbanism

“For forty-one million, you built a playoff team. You lost Damon, Giambi, Isringhausen, Peña and you won more games without them than you did with them. You won the exact same number of games that the Yankees won, but the Yankees spent one point four million per win and you paid two hundred and sixty thousand. I know you’ve taken it in the teeth out there, but the first guy through the wall always gets bloody, always. It’s the threat to not just the way of doing business, but in their minds it’s threatening the game. But really what it’s threatening is their livelihoods, it’s threatening their jobs, it’s threatening the way that they do things. And every time that happens, whether it’s the government or a way of doing business or whatever it is, the people who are holding the reins, have their hands on the switch — they go bat shit crazy. I mean, anybody who’s not tearing their team down right now and rebuilding it using your model, they’re dinosaurs. They’ll be sitting on their ass on the sofa in October, watching the Boston Red Sox win the World Series.”

–From the movie Moneyball: John Henry, Boston Red Sox owner

Since the beginning of the year I have spent numerous hours studying the book and movie Moneyball. Both the book and the movie resonate with me. I grew up playing baseball. I played baseball in college. The sport of baseball appeals to my cerebral nature. It also resonates with me because I see parallels in the story of Moneyball to what is presently taking place in how I believe our built environment is starting to be weighed and measured.

For those that may not be familiar with the story, Moneyball follows the General Manager of the Oakland A’s, Billy Beane, during the course of the 2002 baseball season as he works to keep his team competitive with a small market payroll that is a mere fraction of the big market teams (i.e. New York Yankees). Billy Beane embraces the use of “Sabermetrics”, which is a system for evaluating baseball players using the objectivity of statistics rather than the subjectivity of baseball scouts. Baseball players have been evaluated since the game’s inception by individuals who are measuring talent based on intuition and gut feel. This method of measurement is an inexact science and is littered with bias. A player with tremendous talent might be judged negatively because he “waddles like a duck” when he runs or “looks funny in his baseball uniform”, which probably doesn’t have any bearing on his ability to hit a baseball or throw a strike from the pitcher’s mound.

I believe there are parallels to how our built environment is measured. I believe there are “Sabermetric” standards by which urbanism can and should be measured. I believe there is a fear of the shift that will come as these metrics are identified because it means an end to how many have done things and a potential end to their livelihood unless they accept the paradigm shift that we are in the midst of.

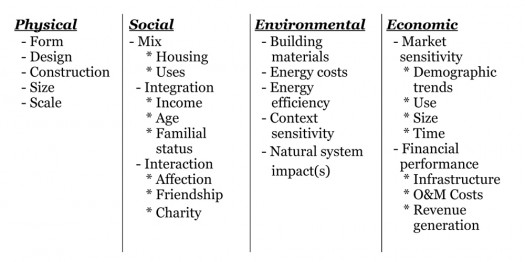

What first has to be understood is identifying the factors that are critical for determining the WHAT and HOW for effectively measuring urbanism. After an extremely stimulating dialogue with fellow Urbanists and friends that I both respect and trust the following factors were identified:

Take a general approach to identifying the metrics of urbanism

Before specific metrics can be identified, the general nature of what is important to measure must be determined. Good decision making often needs discipline to not get ahead of one’s self before understanding what needs to be done.

A good starting point would be to identify the general categories that could potentially be measured that would be contributing factors to great urbanism. Taking an initial first stab at this the categories might include the following:

Make certain that any metric used is measuring appropriately

Urbanism isn’t a recipe that can simply be followed in order to create great places. Urbanism is much more complex than that. The metrics of urbanism aren’t going to directly correlate like a recipe for German Chocolate Cake. Rather, urbanism and the way it is measured must be thought of more as a living entity than an inanimate object. There are a multitude of conditions related to land that will determine the appropriateness of certain measures over others. Measuring inappropriately could potentially lead to measuring the wrong things, the wrong way, and/or with incorrect reasoning. While some principles may work generally for all (i.e. connectivity), other principles may contain higher degrees of sensitivity due to specifics relative to location (i.e. how connectivity is achieved).

For example, block size. This is one that I have a direct sensitivity to because of where I work and live and the often negative connotation associated with Salt Lake City block sizes. There are arguments to be made that a 10 acre block is BAD. If the metric rule is that anything above a particular block size is BAD then Salt Lake City is the bane of urban design. What I have learned through work that has been done by both DPZ and PlaceMakers is that what can potentially make the Salt Lake City 10 acre block detrimental is the application of the 10 acre block, not the size of the block itself. I have heard Andres Duany speak on multiple occasions as to the built-in benefits and flexibility that exist in a Salt Lake City block which other cities with smaller block sizes will never be able to achieve. For example, the 10 acre block, when broken up, can emit a myriad of possibilities that the 2 acre Portland block can never offer.

Work to properly weight the metrics so as to not overly prescribe and hinder the art of creativity

There is an important need to balance art and science. A delicate balance between the two for the purposes of creating great urbanism must exist. This is why the identification of the proper metrics is so critical. Whether we like it or not the nature of land development requires the use of metrics to regulate and govern. This is why I am such a tremendous advocate of the use of form-based codes. Their use “changes the game”, in my opinion, in terms of how our built environment is allowed to be created.

At the same time, we have to be careful about over prescribing and/or not allowing for proper subsidiarity in what is prescribed and when certain decisions are supposed to be made. When either of these instances occurs creativity can be (and usually is) stifled. This can often hurt the opportunity of finding better solutions that could potentially become the new benchmark standard(s) of measurement.

This, in part, is what drew me to the potential correlation between Bill James’ “Sabermetrics”, as discussed in Moneyball, and the necessity to understand what metrics need to be identified in order to effectively measure what urbanism produces. In my mind this is necessary in order to justify the decisions that need to be made regarding the creation, operation, and maintenance of urbanism. We are currently in a period of time where metrics are governing land development with an iron fist on both the financial and governmental sides of the equation. One of my concerns is that if the wrong metrics are used to measure (as in baseball) less effective decision making occurs. This is potentially worse than simply being subjective and going by gut feel. Subjectivity at least requires a working knowledge and first-hand experience. Hiding behind the WRONG numbers, regarding something as difficult to correct as an already built development project, could take decades to correct (if ever).

Include metrics that support broad “market bandwidth”

There is an integral need for flexibility and diversity in system and output. We need systems that allow for a broad level of bandwidth, rather than one that is constrained and narrow. As noted previously, we are subject to economic forces that have to be considered. If one wants to achieve success, from a business standpoint, the means by which absorption can be maximized requires the greatest number of product alternatives with the ability and right to deliver as warranted by market acceptance and a system (regulatory policies) under which this can be delivered. The commodity “output” in real estate is land and the most efficient method for absorption is being able to package it with a multitude of different product alternatives.

Put into the form of an analogy, if you consider that all sandwiches have bread in common, the best way to create “market bandwidth” for the absorption of bread is to have a multitude of alternatives to pair bread with different ingredients that will create different sandwich alternatives. While peanut butter & jelly is a popular sandwich there is room in the market place for other sandwich types. General market acceptance of peanut butter & jelly shouldn’t justify policy constraints to limit other sandwich alternatives. Allow for other sandwiches (market) with parameters for how other sandwiches are to be provided (system)

Recognize the built-in uncertainty due to the “human” factor

Consideration should be given towards a human being’s rights regarding free will (ability to choose) that are associated with the human condition. If there were no free will then urbanism could be entirely formulaic. However, there is the need to understand that certain things can and should be measured. Urbanism should not be subjective, yet at the same time it should also not be ENTIRELY objective.

It is also important to recognize the relationship of disorder in the creation of good urbanism. Disorder is going to be a reality. It will exist, when it comes to the creation of our built environment, due in part to the previous point raised regarding free will. Human beings, through their ability to choose, create a natural level of disorder to everything that they engage. This point is why becoming overly reliant on metrics can be dangerous.

In conclusion, the question I wish to pose is, “What are the Sabermetrics of Urbanism?” What are the metric standards that, when identified, show the true nature of how we should be looking at our built environment in order to determine what is healthy, efficient, socially strengthening, and economically sound? Paraphrasing an idea from Moneyball we need to “challenge the traditional understanding of urbanism by questioning the meaning of its statistics.” If we do this I am confident effective metrics for great urbanism will be found.

Example Moneyball Questions applied to Urbanism:

- Moneyball defines runs as the currency of baseball (Page 131). What is the currency of urbanism?

- Derivative securities are the “fragments” of stocks and bonds (page 129). What are the derivatives of urbanism?

- “Expected Run Value” — Every event on a baseball field alters the state of the game through raising/lowering a team’s chances for producing runs (page 134). What is the urbanism equivalent to “expected run value”?

–Michael Hathorne

Michael Hathorne is a Senior Planning Manager with Suburban Land Reserve in Salt Lake City. Michael’s professional experience includes such areas as community design, property acquisition, land use entitlements, long range land planning, and land use policy. Areas of professional specialty and interest include New Urbanism, Transit-Oriented Development, and Form-Based Code.

Michael presently serves as Chairman of the Local Host Committee overseeing the organization and planning efforts for the national conference of the Congress for the New Urbanism to be held in Salt Lake City, UT on May 29th through June 1st, 2013.

Michael teaches urban planning courses at the University of Utah. He has taught previously at Arizona State University and Brigham Young University.