A Placemaking Journal

Choosing to Overlook the Obvious

I live in an old house that overlooks a single-track CSX rail line. Between my front gate and the train is a two-lane, neighborhood-edge thoroughfare with a speed limit of 35 mph and an average speed closer to 40.

Though it functions as an in-town, city street, it’s classified as a state highway by the Georgia DOT, which means that, while modest in scale, it’s not exactly context-sensitive in its behavior. It’s been repaved many times without being milled, so the historic curbs once in evidence are now long covered up with asphalt, and the 4 and a half-foot sidewalk that runs along it is separated by a planting strip of 24 inches or less (depending on the block) which, ironically, can’t legally be planted with anything other than grass.

Chuck Marohn of Strong Towns might classify it as a baby–stroad.

So, pedestrians, sliver of grass, no curb and speeding traffic. Not ideal. Yes, because it basically predates the automobile, the sidewalk succeeds in terms of functionality — it’ll keep you out of the street and get you where you’re going — but it’s not a pleasant walk and it doesn’t feel particularly safe.

I tell you all this for context, so the following anecdote will make sense.

Years ago, when our now 13 year old daughter was a baby, we had numerous instances when visitors — in from a variety of Atlanta’s growing suburbs — would stand on our front porch, look out, and say some variation of this: “Now that you have a child, are you worried about… the train?”

Uh, whah?

Here they were, in full view of the relentless stream of traffic cruising up and down the street, fully aware of the sidewalk condition and its proximity to cars and trucks, yet the alarm bells in their heads saw only railroad tracks, the most benign aspect of the entire scene.

Consider the stats: Every year, the U.S. sees between 450 and 600 pedestrian deaths related to railroads, 20-50% of which, according to the Federal Railroad Administration, are intentional suicides. Meanwhile, about 4,000 pedestrians a year are killed on streets and roads, and just shy of 60,000 are hurt.

Now obviously any death or injury is a tragedy and I’m in no way trying to minimize loss. I’m simply illustrating a huge disparity between actual danger and perceived danger.

I’ve thought a lot about these exchanges in the years since and think I’ve developed a pretty good idea what’s happening. In short, it’s about control. We like to feel like we’re taking care of ourselves, our dependents and our communities, so our brains simply tune out anything that might suggest that our own behavior is in some way complicit in the problem.

Driving is so commonplace, such an integral part of our modern existence, that it, or its commensurate infrastructure, no longer seems to register as problematic or dangerous. It’s just the way things are and can therefore be mentally tabled as something we’re flat out incapable of influencing.

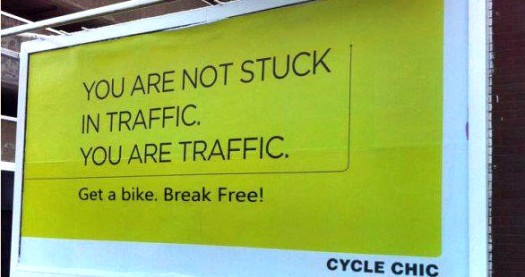

It’s the obstacle between us and actual reform. Check out this billboard that was bouncing around the socialsphere this week. A campaign whose sole point is reminding people that the root of the traffic problem is — d’oh — too many people doing exactly what we’re doing.

Real change, the kind that adds up to meaningful improvements in our quality of life, is hard. It takes a lot more than just bitching about traffic and keeping our kids off the railroad tracks. And that’s why we’ve trained ourselves to look past those things that force confrontation with reality. To just focus on the easy stuff.

Consider this picture shared recently by Mike Lydon of the Street Plans Collaborative:

I’ve come to believe that most people might look at it and think, that’s nice. We should encourage public art where we live. Except that it’s a classic chicken and egg scenario. The place didn’t become endearing because of the art. The art came to be through the appeal of the place. Through its welcoming civic space, together with the dwellings and commerce that define the bulk of how we commit our lives, not just to our surroundings but to each other. In short, the photo captures a place built around the needs and aspirations of people, and that connection is reflected in the art it inspires.

But without the hard work of placemaking and just the fostering of public art, you might end up with something like this:

Or, if you think that’s an unfair example because I’ve used a bombed-out, left-for-dead strip mall for dramatic effect and, to be fair, there are plenty of viable and successful places littered throughout our sprawling landscapes, then fine. Have this instead:

Either way, it’s just not the same. Places worthy of our affection or, in the words of Jim Kunstler, worth defending, are not built on band-aid solutions to simple problems. Instead, they emerge from hard fought cultural consensus. From collective desires for change and the collective will to participate in what it takes to get there.

Greatness is no easy pursuit, which is why truly great places are in such short supply. But it is possible. And it begins with acknowledging the obvious.

–Scott Doyon

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.