A Placemaking Journal

Municipal Placemaking Mistakes 04: No models for emulation

Emulation is more than just the highest form of flattery. It’s also a key factor in effective placemaking.

Yes, in the course of a meaningful visioning process, the naming of a specific place as a model for emulation is not absolutely necessary, but its benefits are so great that failing to do so constitutes one of the most critical mistakes you can make. Not because you should be identical to somewhere else but, rather, because you’re more effective developing a vision in terms of something real, proven and reliable, employing whatever tweaks or qualifications necessary to make it appropriate for your own community.

Mistake #4: Failing to identify an existing place as a model for emulation.

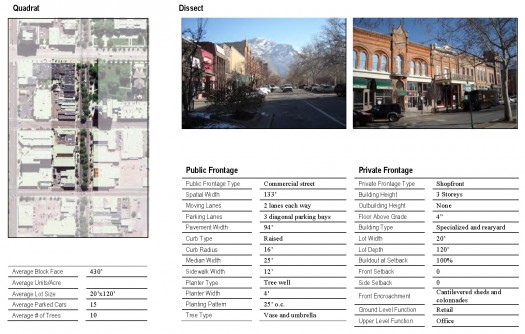

The more precise you can be in this endeavor, the better. That is why it is common for planners to use Synoptic Surveys that measure the important details of your model.

Benefits

The four benefits of identifying a model or precedent (you need not limit yourself to one) are:

1. Building Stronger Consensus

If the development of your meaningful vision only consists of words (e.g., “we want to create a vibrant downtown that is pedestrian-friendly”), the consensus might be shaky since those words mean different things to different people. For example, what do those words demand from a perspective of thoroughfare width, parking, or private frontage requirements?

If you describe your meaningful vision in terms of an existing place there is less chance that people will be talking past one another.

Having the discipline to name a specific place or series of places also makes ongoing consensus-building substantially easier by providing something that can be visited and experienced by key decision-makers who may not have been involved at the time of the vision’s creation.

2. Reducing Failed Experimentation

If your proposed vision includes ideas and characteristics that do not exist anywhere on the planet (i.e., you do not have a model), that raises the huge red flag of “experimentation.” From a placemaking perspective, experimentation has not been kind to our cities; e.g.’s, pedestrian malls, suburban building types in urban settings, one way streets, bans on mixed use, sunken plazas, etc.

The default setting should be to demand places that have a proven track record of success. Anything less is asking for trouble.

3. Mitigating the Scope of Single-Issue Specialization

Every meaningful vision will be attacked by single-issue specialists. You know the issues — retailers say that there is never enough parking, neighbors claim that the densities are too high, commuters argue that congestion must be eliminated, fire chiefs say that the roads are too narrow, etc.

The key isn’t to eliminate the concerns, but to address them with reference to an existing place that turns the argument away from a single-issue discussion to a holistic analysis; i.e., where the issue is placed into its proper context as opposed to an isolated context.

For example, if a specialist-minded person argues that parking should be more convenient for retailers, is your argument that it should be less convenient? The better argument is to analyze the issue as part of the overall placemaking puzzle — and having another place that serves as your model will highlight the necessity of balancing the various issues as opposed to “solving” one issue, only to find that it created three other more substantial problems.

4. Increasing Efficiency of the Decision-Making Process

Placemaking by its very nature is a complicated task filled with conflict among different people with different priorities. When conflict arises, a great tool for resolving it is to learn from others who have already dealt with the problem.

For example, when a builder at The Waters development painted a speculative house purple in violation of the development color code, the development team could have spent a lot of time and resources debating the merits of the shade of purple. Instead, the developer asked how the communities that served as models for The Waters (I’On and Habersham) handled the issue of purple houses.

Identifying a model will save time and resources when it comes time to implement, and also permit the discussion to be more substantive and less esoteric and emotional.

–Nathan Norris

Series Overview: Through a series of periodic posts, Nathan Norris will explore how cities hinder their own placemaking efforts, wasting time and money by investing in tools, policies and programs that deliver lousy results. In the process, we’ll be looking to you to help flesh out the content through examples, personal experiences and links to additional resources. The goal? A one-stop, crowdsourced primer for cities and towns seeking advantage in an ever-competitive world.

To view the entire series to date, click here.

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.