A Placemaking Journal

Retail: When it bends the rules and breaks the law

Getting ready for a TEDx talk in a few weeks, I’ve once again been noticing how the places that I love the most usually break the law. The contemporary development codes and bylaws, that is, which are geared to the car, not to the pedestrian and cyclist.

Then last week’s urban retail SmartCode tweetchat with Bob Gibbs sparked a debate about the rules of thumb that govern the success or failure of the most risky development of all: retail. And when those rules might be bent by certain special circumstances.

Ready to geek out with me for a moment?

Newtonian Physics

To contemplate the non-idealities of life, let’s start with the laws of physics. All of classical mechanics – and Newton’s Laws upon which they are founded – have both their ideal statement of law, and then all sorts of corollaries for when non-idealities happen. Rarely, even in our physical world, do ideal states occur.

Newton’s Laws

1. A body in motion (or at rest) stays in motion (or at rest), unless acted on by an outside force.

2. Force = mass x acceleration.

3. Every action has an equal and opposite reaction.

I remember as a young electrical engineering student struggling with the fact that there are significantly more corollaries than there are laws. Back then it made me write an epigram about that irony:

Learning a lie so that we can understand the truth.

Quantum Physics

When things are very small or very fast, classical mechanics’ laws – as well as their corollaries – do not hold true. Then you’re into the realm of quantum physics where things get very interesting.

Everything boils down to relationships, probabilities, and the fact that when things get small and fast, they act quite differently. Sound a little bit like our economy?

An electron may sometimes act like a particle, and other times act like a wave. And whether or not it tunnels makes a big difference to all the silicon-based artificial intelligence in your life.

So back to urbanism. When are rules bent and laws broken that shape our everyday community? We’ve talked extensively about when laws are rescinded to get in line with local character, or circumvented by grandfathering.

To get new development in harmony with local character, cities are often using the form-based SmartCode. However, it can’t be emphasized enough that the SmartCode is a model template that must be customized for local character. It’s not exactly a law-corollary relationship, but something close.

How about urban retail rules of thumb, and when don’t hold they true?

Retail Rules

Let’s look for a moment at some of the key rules of retail. And the numbers that influence our buying habits. Concise rules of human behavior govern whether retail will be successful. But these rules have many corollaries.

Bob Gibbs was highlighting these rules in last week’s PlaceMaking@Work webinar. If you’d like to pop the hood on retail, Yarmir Steiner and other leading retail developers recommend Gibbs’ new book, Principles of Urban Retail Planning and Development. You’ll be seeing more reviews soon, but here’s a peek.

Over Supply: The US has 20 SF of retail per person. That’s massive in comparison to other countries; the next closest are Sweden at 3.3 and the UK at 2.5 SF of retail per person. So if you’re going to build more, it’s gotta be good.

Downtown Market Share: Until the mid 60’s, downtowns captured about 80% of the trade area, which was typically the county. Most downtowns declined not for market reasons, but for ill-conceived planning reasons.

Now the average American downtown only captures about 2% of the retail market share of its community. The rest is sold in malls, strip centers, and online. This is defining downtown as the central business district. However, an ideal goal is a 50% capture of retail needs in each neighbourhood, including downtown.

Charleston is a great example of sustainable retail for mid-sized cities, thanks in large part to Major Joe Riley making his first retail goal to sell what his residents need. The various districts reinforce each other, and draw plum tenants. The Apple Store chose to locate on King Street instead of in the four malls in Charleston because of predictable urbanism.

8 Second Rule: It takes about 8 seconds to walk past a standard main street storefront. The average person decides in about 1.5 seconds whether to walk in. SmartCode requirements for glazing, private frontage, signage, and public frontage assembly are key.

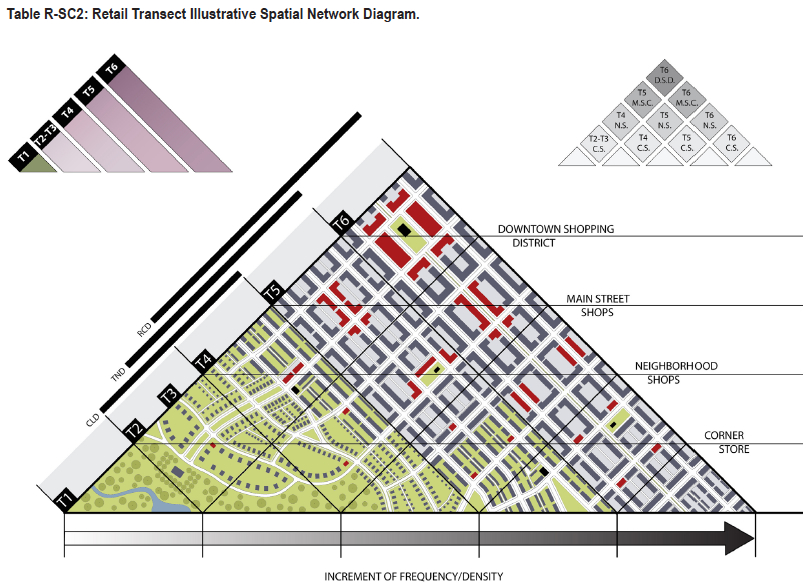

Retail Transect: Retail character must change significantly along the rural-to-urban Transect in order to be successful. Two SmartCode Retail Modules lay out goals and methods for bringing retail back downtown. Retail: Sustainable Commerce by Seth Harry (4.3mb .zip) and Retail Markets by Bob Gibbs (1.8mb .zip). Very important to both of these, as with the model form-based SmartCode, is that they must be calibrated locally.

Corner Stores generally need 1,000 housetops to be successful. While this rule of thumb has many corollaries including housetop reductions for selling gas, or for when construction workers are present or for resort communities, this was one of those argued points on the tweetchat.

Yesterday Steve Mouzon published a followup retail blogoff. I don’t argue with most of Steve’s points, but he’s clearly overlooking the fact that resorts were part of the corollaries that were exempted from this rule of thumb. The SmartCode Retail Module would be calibrated for resort in that case, drastically reducing the 1,000 to a few hundred. Also many of his examples are part of T5 main street, and not the T4 corner store that Bob was addressing, surrounded primarily by residential.

When we dug down into some examples on the tweetchat, the conclusion was that many new corner stores in walkable places are subsidized. Because retail was viewed as an amenity, the developers are often willing for this investment. However, now there’s a new need to get resilient. Strategically placed retail is more essential than ever in soft markets, and will continue to be so as long as signs of the recession remain. In some places where subsidies are no longer available, retail may need to go indie and get tactical.

Live-Works. The sweet spot for a retailer is 1200 SF for the retail portion of live-work units. The average live-work usually marginalizes the retail by making it too small. An example of getting it right is Eton Station in Birmingham, MI.

Hours: 70% of all sales are after 5 pm. A downtown that closes at 5 is immediately giving up the market share. People are spending more money in less time – today’s woman will spend more money in 20 minutes than her mom did in 2 hours.

Parking is one of the most important determinants in sustainable retail. Convenient centers need convenient parking; Main Streets must offer on-street parking.

Nationally, required parking quantities have been cut in half to 4-5 cars per 1000 SF of building by most retailers. More parking is required for stand-alone stores than mixed-use centers. Recent research has found that mixed use centers and even large regional suburban malls only require 2.3-2.6 cars per 1000 of gross building square feet, even during peak demand periods.

New Economy: Post recession shopping centers are becoming one level, in a main street walkable format. They are surface parked with various land uses mixed horizontally rather than vertically.

Pier Park Town Center in Panama City sports 1-story buildings, strip center priced construction, and tenants in a main street, walkable format. We’re often told full sized department stores don’t belong in walkable urbanism, but history shows they are appropriate and necessary.

Retail Performance: In 2010, average sales were $80/SF for independent retailers, $275/SF for malls, and $575/SF for the highest performing centers. Typically rents are 8-10% of gross sales. Downtowns that get the retail rules right can outperform the best malls: tenant mix, anchor, hours, parking policy, private frontage, and costs. Urban centers, to be sustainable, need to be more than employment and residential centers.

Controlling Costs. Lifestyle centers cost $350-400/SF to build, while simple landscaping and architectural details can make a good main street cost about as much, and outperform the lifestyle center. Central to our urban retail goals is to make walkable urbanism more profitable than auto-centric sprawling patterns.

While much of the national retailer perspective will stay the same, there are all sorts of corollaries to many of these retail rules. And every now and then, they almost go quantum.

– Hazel Borys

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.