A Placemaking Journal

“Sustainability” is so ten years ago — Let’s talk “Resilience”

Deep in an April 14 New York Times story on the aftermath of the Japanese earthquake and tsunami was mention of an iPhone app called Yurekuru that gives warning of an impending quake. The name, said the Times, translates into English roughly as, “the shaking is coming.”

Before the March 11 quake, the app attracted 100,000 users. Now: 1.5 million.

In a sense, living organisms could always be fairly certain that a shaking of some kind was on the way. Life on earth has been shaped by violence, by sudden upheavals and reversals of fortune for one hapless population or another. Foreboding is written into the human psyche. It’s only recently that we’ve felt entitled to be spared.

It’s an expectation ungrounded in reality. But it has its good points. If we don’t believe that everything is out of our control, we are motivated to take charge of some things. We can organize ourselves to survive. Which is why, in the developed parts of the world, at least, earthquakes, tsunamis, wildfires, hurricanes and other catastrophic acts kill far fewer people than they did a century or so ago, even when horrific events take place in more populous areas.

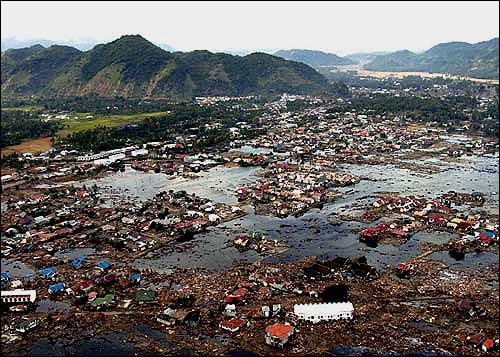

Maybe because the 200,000 death toll was so dramatic, the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami challenged scientists who applied our modern assumption of a right to survive and bounce back from calamities to the study of resilience strategies. And much of what they discovered not only helped agencies and communities fine-tune emergency response techniques, it expanded the market for ideas scientists have been thinking about for generations to an audience made suddenly attentive by the life and death implications of their theories.

Resilience thinking is systems thinking. Complex, interconnected systems – systems within systems – are reality’s engines. And they are made even more complex by ways in which their components adapt to new situations. Continuous adaptability makes the systems dynamic, always changing into something else. The change may be slow and predictable. But maybe not. Sometimes giant tectonic plates shift and the shaking comes.

What scientists learned from the aftermath of the 2004 tsunami is that some communities were better than others at adapting to the sudden, violent change and bouncing back. They faced the complex adaptability of nature with adaptable systems of their own. They had responsive leadership networks that people trusted. They had developed diverse economies in which some sectors might recover faster and support the recovery of others.

I was reminded of this over the last year working in Coastal Alabama in the aftermath of the BP oil spill. I wrote about our report, “A Roadmap to Resilience,” here. The one-year anniversary of the spill will be April 20. And the lessons many are taking away from the experience is that the ways in which many communities in the region organized themselves were not sustainable.

Living in the path of potential catastrophe, whether from oil spills or hurricanes or a sudden churning in the world economy, requires flexibility and adaptability. And those attributes were in shorter supply than we imagined in a region overly dependent on tourism and on seafood harvesting and processing.

Fortunately, Coastal Alabama may be applying the lessons of resilience in ways that might serve as a model for other communities and regions in the path of disaster. That’s a pretty broad universe. For eventually, the shaking comes.

–Ben Brown