A Placemaking Journal

Gentrification: We’re both the problem and the solution

Almost twenty years ago, just married, my wife and I bought an old house in a friendly but economically depressed old neighborhood. It was, at the time, a predominantly black neighborhood though, like many historic neighborhoods in and around Atlanta that predate our tumultuous, race-driven urban disinvestment of the 60s and 70s, it had also been a predominantly white neighborhood at one point as well.

Its history is significant and, in the almost two decades since, the process of absorbing and understanding it has been a meaningful one. But at the time, all those issues, together with the baggage that accompanies them, simply weren’t on our radar.

Like most people, our understanding was shaped by the lens of our own circumstance. And that circumstance was that we were relatively broke. Yes, we both had white collar jobs but they were the lowest-of-entry-level and we had a lot of work and dues-paying ahead of us before any sense of expendable income might materialize.

More than anything, we were drawn by the prospect of affordable housing, and required a special government mortgage for limited income buyers to even make it possible. No, we weren’t poor in the sense that we both had the privilege of a middle class upbringing and the benefit of higher education (I get that poverty, beyond just a measure of wealth, is often infused with an additional burden of limited prospects) but we were clearly a lot poorer than the family who sold us the house. They were doing just fine and certainly weren’t being displaced. In fact, they were trading up to a grander house several blocks away.

We wanted a place to put down roots, fix up an old house, and stay for the long haul. We were drawn by value — the kind of life we wanted at a price we could actually afford — and benefited from the fact that we were what demographers and real estate developers call risk oblivious — the lowest rung on the sequential ladder of neighborhood change. In short, we were too young, too clueless, and too enamored of the house and its physical context, to think much about crime, schools, race, class, investment potential or anything else.

We stumbled into something that, in the years since, has served us well. So, does that make us gentrifiers?

No good deed goes unpunished

A year or two thereafter came a spirited and engaged woman who bought a bungalow about a mile away. Drawn by many of the same qualities that appealed to us, and carrying with her the spirit of her modest upbringing in a small, rural Georgia town, she was all about community. Not in the way that the word gets used as a marketing gimmick but in the way community has existed for millennia: Connecting with those around you, coming to understand them as people, growing increasingly interdependent, and working together to create a better place to live.

She was constantly plugged in. Not just with recent residents but with those who’d been around many, many years. To my eyes, she didn’t even see a distinction between the two. But if there were community meetings or initiatives or events to bring folks young and old, black and white, together to help mitigate things like crime or disconnection or aging or cultural conflict, you’d find her there, chipping in.

Personally, I credit her (together with many other people) for creating a lot of value over the years. Compassionate value. But that’s where irony steps in. Because value, once created, doesn’t just sit quietly in a vacuum. It attracts people and money and change at an increasingly accelerated pace. After the risk oblivious — my wife and me in our youthful naiveté — come the risk aware (folks who recognize the challenges associated with disadvantaged or depressed areas but are willing to accept them, at least conditionally) and, finally, the risk averse (those who’re only attracted to an area once certain levels of safety, predictability and comfort present themselves).

That’s where our neighborhood is today. A magnet for the largely affluent risk averse. Property values and, with them, property taxes have skyrocketed, which has put a new level of strain on those — my friend included — of limited financial resources.

That’s why, not so long ago, she chose to sell that house and move on. The quality of life she helped create, and which subsequently enhanced the broader appeal of our neighborhood, ultimately conspired against her. Her years of effort were rewarded with an economic invitation to move on.

Of course, the appreciation she experienced on her property also allowed her to buy her next home outright. So, was she a gentrifier? Or was she a casualty?

Is it possible to be both?

Not so black and white

Fueled by the demographic bulk and emerging urban sensibilities of both the Baby Boomers and the Millennials, American cities — and city neighborhoods — are finding themselves increasingly attractive to outside investment. Not necessarily because they’re affordable (in many areas, that ship has sailed) but because they deliver the things people are looking for — walkable, car-lite or car-free convenience, neighborhood schools, and architectural charm to name but a few.

As these preferences and settlement patterns change, demand is outstripping supply, with the predictable results that entails. Today, new money is flowing into some disadvantaged or undervalued places at a rate that’s, frankly, a little hard to fathom. As are the inevitable social conflicts that erupt anytime people with no real shared experience or perspective begin exercising a sense of ownership and belonging over shared space.

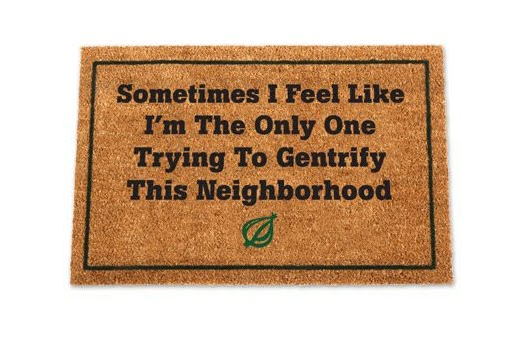

It ain’t pretty. Today’s everyday in-town neighborhood newcomers are more affluent than ever before and affluent people who pay premium prices don’t necessarily want to contend with things outside the comfort of their own reality. Which means they often come across as culturally tone deaf and insistent upon remaking a neighborhood to serve only the narrow spectrum of their own needs and desires.

If you read a lot about gentrification, or discuss it with those directly impacted, you’ll frequently find these types of behaviors described as exemplifying a sense of entitlement: Cultural overhaul with no regard for place, people or history.

It’s not an unfounded characterization. But it’s only half the reason why gentrification is such a messy and divisive issue. The other half is the all-too-prevalent premise that newcomers simply aren’t a part of the neighborhood. That their presence is that of unwelcome guest rather than neighbor. That, despite being a resident, they just haven’t earned it.

That’s just as wrong.

Such newcomers may be painfully clueless. They may be culturally tone deaf. They may even be dismissive but, for better or worse, their presence alone makes them part of the community and that needs to be acknowledged. If not, you end up with two types of entitlement going on: Newcomers who think they’re entitled to just run roughshod, remaking the neighborhood to serve their own narrow band of interests; but also long-timers who think they’re somehow entitled to a world without change.

The people around you are in your life. Whether you like it or not.

I offer these anecdotes not to argue whether or not I, or my wife, or our friend meet one of the many conflicting definitions of gentrifier, but as a means of demonstrating that what constitutes gentrification — and whether or not it’s a positive or negative phenomenon — is not always an easy distinction. For example, is it gentrification when a white person moves into a black neighborhood? Or when an affluent person moves into a poor or working class neighborhood? Or does it require some level of dismissal and exploitation of long-time residents and their far deeper emotional and social attachments?

I can’t necessarily answer that and, if you Google “gentrification,” you’ll see why. There’s a treasure trove of perspective to be found, on both sides of the issue, and it’s all valid. Not because each and every link speaks some venerable truth but because each reflects the world through the eyes of one person — one human being — and that’s a nice proxy for what community actually is: A diverse collection of individuals with a shared, if reluctant, interest in each other and a need to unite — respectfully and empathetically — in pursuit of mutual goals.

If your neighborhood is divvied up as old vs. new, or rich vs. poor, or white collar vs. blue collar, or black vs. white, or any number of ways people succumb to their most divisive and least appealing tendencies, and your actions serve to reinforce those distinctions rather than overcome them then, well, good luck with that.

Managing change, directing it, channelling it, or even mitigating it is no small endeavor. But neighborhoods in transition have the opportunity to try. To commit themselves to pursuing reality-based strategies that respectfully unite people, leverage their talents and resources, mitigate conflicts, and prevent what’s ultimately the worst possible outcome at either end of the spectrum: monoculture.

But it only works if everyone — of every status — works together. Wherever you sit in the equation, us vs. them simply ain’t gonna cut it.

–Scott Doyon

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.