A Placemaking Journal

Connected? Walkable urbanism, active kids, and Olympic gold

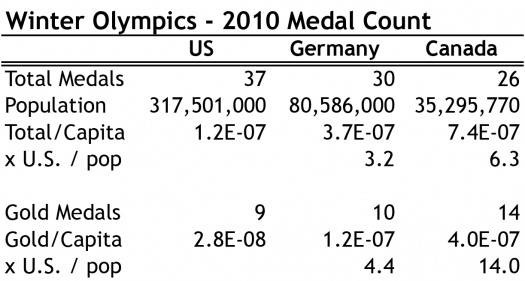

Last Friday, our nine-year-old came home from school talking nonstop Olympics. He went on for awhile about 2010 medal counts, with Canada taking home 14 golds in Vancouver, the record for any country at Winter Olympics. The deep polar vortex we’ve been trudging through this winter has to have some silver lining, so perhaps being better at Winter Olympics is part of the payoff for our wintry country. #WeAreWinter. However, I couldn’t help but thinking about Suburban Nation’s account of Canadian urbanism, and wondering if there’s any cause and effect between walkable urbanism, active kids, and Olympic gold.

With national pride at a global high everywhere, the spirit of celebration is infectious. So here’s to celebrating the city planning policy that Canada got right in previous decades, and taking a hard look at what we’re enabling today. As the United State’s largest trading partner, Canada experiences significant influence from south of the border. But in many ways, the two countries are distinctively different. City planning is one of those ways, partially rooted in “peace, order and good government” versus “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

A few key urban policy decisions after World War II created a different built environment in the two countries for a generation. In the US, the Federal Housing Administration and Veterans Administration were providing WWII vets low interest mortgages for single-family, suburban homes. In Canada, the government instead encouraged veterans to renovate old housing stock, row houses, and mixed-use buildings, which concentrated development within older neighbourhoods.

At the same time, the US Federal Highway Administration built a 41,000-mile interstate highway system, which often cut through the hearts of cities, doing away with swaths of walkability and connections for commerce. Those millions of new homes out in the suburbs became cheaper for the users thanks to the interstates, betting that the devaluation of the core would offset the new value in the dispersed city. In Canada, highway revolts stopped freeways into and through most Canadian downtowns. With a larger landmass than the US but with about 1/10th the population, sprawl also naturally occurred slower north of the border.

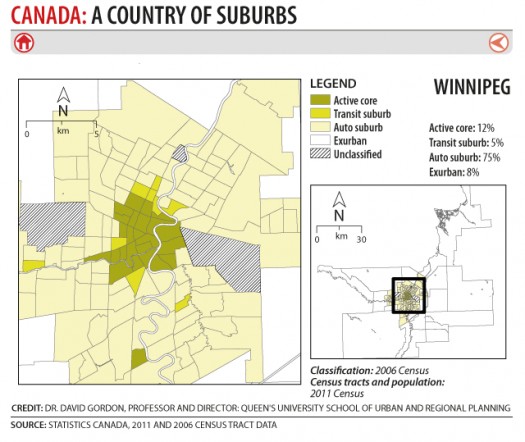

Unfortunately, Canada’s positive post-war policy decisions have eroded, adopting a US approach to far-flung subdivisions. Queen’s University urban planner Professor David Gordon released a Canadian Suburbs study last year, indicating over two-thirds of the nation’s population live in some form of suburban neighbourhood. Canada’s growth rate from 2006 to 2011 exceeded that of the United States by nearly one-third, but during that time 95% of metropolitan area growth was in suburban areas. Perhaps one reason I love my city is that I live in the Active Core, with active transportation levels at 1.5x our metro average. However, the concerning numbers of this study for Winnipeg is that while the walkable core has grown by 9% and suburbs by 2% from 1996-2006, the exurbs shot up by 15%.

The word on the street is that our Winter Olympic gold has more to do with the strong support of corporate sponsors and dependable winters, but I’d still like to see an international walkability index for urbanized areas of countries. And more outdoor, year-round living with compact urbanism incentivized locally and across Canada – here’s a litany on why that makes sense in winter cities. Until then, the following photos are a little inspiration from Winnipeg’s serious winter.

–Hazel Borys

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.